It’s hard to think of a $21 million dollar motion picture as a “cult movie” but that’s what Brian DePalma’s 1983 Scarface almost became until it was saved by an audience that the filmmakers never had in mind.

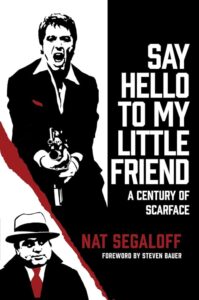

A cult movie is nothing to be ashamed of; The Rocky Horror Picture Show, Donnie Darko, and The Wicker Man, for example, are commendable as cinema, they just didn’t catch on the first time out. That’s the key: a movie that everybody sees isn’t a cult, it’s a hit. Cult status is reserved for the movies that people discover on their own. And that’s what happened to Brian DePalma’s remake of Howard Hawk’s 1932 original Scarface. Both films are the subject of Say Hello to My Little Friend: A Century of Scarface by Nat Segaloff. The book, coming on the hooves of Segaloff’s The Exorcist Legacy: 50 Years of Fear, is also from Citadel Press.

On December 9, 1983 when Martin Bregman produced, and Universal Pictures released, Scarface, starring Al Pacino, Michelle Pfeiffer, and Steven Bauer, everybody had high hopes. It was a stylish, dynamic modern gangster movie in which Pacino embodied Tony Montana, a Cuban exile who rises to the top of Miami’s cocaine trade but who, like all megalomaniacs, is ultimately undone by his wretched excess. In Tony’s particular case the fall is a bloodbath in which, at its height, he pulls a rocket rifle on his foes and sneers, “Say hello to my little friend” before blowing them to bits and, soon thereafter, meets the same fate. It was produced at a cost of $21 million according to Bregman (and as much as $37 million according to other sources). Critics were not thrilled with it, many objecting to the excessive violence and operatic-level performances, and audiences shied away from its shocking dramatic situations and F-word-heavy language (200 uses, give or take). With only word-of-mouth to propel it (this was years before social media), the film’s initial gross of $66 million (per boxofficemojo.com) was a disappointment.

But then something happened, though it took a few years. When it came out on VHS tape and showed up on premium cable TV, a whole different audience started watching it than Universal had expected: people of color.

“Scarface was dead and buried until hip-hop rediscovered it,” said Steven Bauer, who co-starred with Pacino as Manny Ribera, Tony Montana’s friend and confidante. “In the early 90s I would start getting recognized on the street by rappers. They would say, ‘Oh, I gotta give you respect—that’s the movie.’ I didn’t know all of them, so I would have to ask someone, ‘Who was that?’”

“After Scarface comes out, the effect on my crew of those who went to see it immediately was overwhelming,” recalls music executive Bill Stephney, who created the rap group Public Enemy with his friend Chuck D. “Everybody’s speaking in a Tony Montana patois accent and quoting him. It’s a phenomenon. Around ‘80 and ‘84 hip-hop is developing in the New York area, and then the movie comes out that celebrates a guy on the streets with nothing [who turns] the drug trade into a fortune. I think that resonated with young black men who were largely being raised by the culture of hip-hop, of aggression, of an in-your-face aspect to the culture. Tony Montana and Scarface [are] a foundational influence for hip-hop.”

Why did it take a new generation to discover Scarface? Prevailing wisdom says that young people born into the 70s and 80s saw their own values and aspirations reflected on the screen, and those aspirations were in cynical conflict with those of their parents. “I started to hear Scarface mentioned on the MTV Crib shows,” says Charles Coletta, PhD, professor of popular culture at Bowling Green State University. Cribs began in 2000 visiting (as the promos said) “the domestic sanctuaries that some of today’s most favorite stars call home.” Some of them would make Tony Montana’s mansion look like a Motel 6.

“Not that I was a frequent watcher,” Coletta goes on, “but I did notice that a lot of the hip-hop and rappers did like it. I think a lot of it goes back to that gangster persona or archetype in American popular culture: someone who’s independent, maybe a little shady, but they’re a go-getter and they see what they want and they go get it. That archetype resonates, and it’s such an over-the-top film that people just get immersed in it.”

What’s interesting is that African-American audiences see Scarface as their story even though Black actors have no significant presence in the film. Bill Stephney says it’s because the story transcends race: “For that generation—for those who are nineteen, twenty, or twenty-one in 1983 to 1984—you’re a product of the Civil Rights generation and integration. You’re relating to people beyond race. We thought, from our generation, that white people were segregated on the basis of race, not black people. Tony Montana, for teenagers, at that point, is just a cool guy that teenagers are into.

“It developed this cult status,” he continues. I always say that you probably can put the impact of Scarface culturally in the area of young black males who decide that the drug game, even if they had a mom who was a teacher and a dad who was a corrections officer, fell in love with the romanticism they found in Scarface, and that’s where the energy for gangsters and hip-hop derive from.”

“The urban audience took a shine to it and really could relate to it in some deep way,” says Kevin Goetz, author of the book Audience-ology: How Moviegoers Shape the Films We Love and whose company, Screen Engine/ASI, does audience testing. “I believe people are enamored by Tony and his story. I think, at the heart of it, there is this unabashedly, unapologetic character in Tony that was, in some way, the ultimate underdog. There have certainly been a number of underdog stories, but this is a true immigrant experience and, in its own perverse way, it’s the American Dream. There’s an archetypal reason for it resonating, particularly with disenfranchised groups.”

Scarface is an unashamed 170-minute commercial for over-indulgence. Audiences, particularly in communities of color, are attracted to it because of Tony’s excess and the unfiltered joy he takes in getting even with his enemies. The irony is that this is the exact opposite of the argument its producers made to persuade the MPAA Ratings Board to change the film from an “X” to an “R,” namely that Tony gets his comeuppance at the end, so how could it inspire young people to enter the sordid drug trade? “But the movie is more about the journey, not the ending,” notes Kevin Goetz.

Fans can even share in the journey with such merchandising opportunities as T-shirts, sport shirts, shorts, athletic jackets, socks, hoodies, sunglasses, blankets, wall clocks, posters, stickers, mugs, and even neon signs that flash the film’s ironic moral motto, “The World is Yours.” Together with video games, numerous CDs of Georgio Moroder’s throbbing musical score, and the continuing sale of anniversary DVD and Blu-ray editions, Scarface should be well into profits by now, on paper, at least.

Not bad for a movie that pushed the limits, broke the rules, got its first audience wrong, and sidetracked the careers of the talented yet unknowingly prescient people who created it.

***