In 1933, Lawrence Shead was found brutally murdered, “lying unclothed on a bed in the [his] two room apartment” in Patterson, New Jersey. The accounts of Shead’s murder were rife with discrepancies: according to one paper, a rowdy party preceded the killing, while another reported it as an “intimate gathering”; depending on the report, the object used to strike Shead was either blunt or sharp. There was only one consistent detail: the guests-turned-attackers had surprised an unsuspecting Shead. Unclothed, in bed, and asleep, the thirty-five-year-old was beaten to death. There was no mention of the words “gay” or “homosexual,” but the queer subtext was clear: Shead had been a gay man in 1930s America. The newspaper reports would have you believe he got what was coming for him.

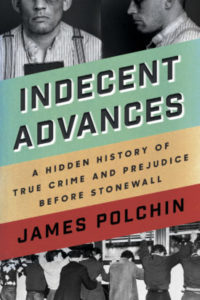

Murders like this were not uncommon in the decades before the Stonewall uprising, but they had only received brief mention in the queer histories that were written, which focus more on the greater story about perseverance against prejudice. It isn’t until now, 50 years later, that queer true crime in the first half of the 20th century is being told. On and off over the past 15 years, James Polchin, a writer, historian, and NYU professor, pored through newly digitized newspapers to uncover the murders of men killed at the hands of other men who claimed they were driven to violence by the victim’s “indecent advances.” Published earlier this month, Polchin’s true crime history, Indecent Advances: A Hidden History of True Crime and Prejudice Before Stonewall, resurrects these lives and exposes the forces—social, medical, legal, and political—that worked together to criminalize queer men.

There’s seemingly no one better than Polchin to unearth and make sense of these stories. Self-assured and with exquisite posture, he’s remarkably articulate and speaks with the careful syntax of a natural born writer—someone whose lucidity of thought is challenged and exercised daily in the classroom. When we met, he had just come off interviews with Vox and WNYC, and spoke of the challenge of translating these years of research and private grappling, of sitting quietly and in solitude, into public space. You wouldn’t know this was a struggle.

***

Both a social history and a true crime page-turner—a primer in the evolution of American thinking about sexuality as well as a compelling account of the murders that “equated brutal violence with homosexual encounters in the public imagination”—Indecent Advances opened my eyes to a history I didn’t know and pained me to learn. I read it slowly, letting the mosaic of tragedies take shape around me as I was immersed in a time and a national frequency, when the country vibrated with panic about the state of sexuality (the acceptable dose of testosterone was not a hair too macho or too feminine, for to waver—in either direction—was to suggest you fell somewhere beyond the constricted arena of “normalcy”). Queer men were trapped in a pocket of the oversized clothing assigned to society’s most feared composite: the sexual psychopath. Moral authority over the nature of homosexuality became a tug-of-war between the medical profession and the law, each responding to the perceived dangers that were seen as intrinsic to the queer experience. And across the country, men were murdered, killed in hotel rooms and back alleys, in parks and ports.

The problem, as it was seen, was not the killing of gay men, but homosexuality itself, which criminologists viewed as a social ill that required vigilant policing, and psychologists saw as a condition that could be treated with social isolation and conversion therapies. Even as theories about sexuality evolved, murder was, more often than not, understood as a reasonable response to sexual solicitations. And it was always the same story: one man met another (or two or three) at a bar or on the streets; they went to an apartment or a hotel or a park, where one man was then killed. The aggressor claimed “indecent advances” had provoked his ultra-violent actions, and he almost always went under-punished. Gay men were put in a constant state of danger, publicly and privately, and in turn, were portrayed by the press as the assailant in their own murders.

“The newspaper reports were really a vital way in which people at the time encountered ideas about homosexuality,” Polchin said. “The crime stories concentrated so many of the period’s anxieties—about deviancy and normalcy, what constitutes the two, questions of justice, questions of the legal system and right and wrong. It was all playing out in terms of how we understood sexuality itself.” As newspapers nationwide were ablaze with sensationalized accounts of gruesome murders, the image of the queer man in America became synonymous with that of a dangerous sex deviant.

The ‘20s and ‘30s saw the explosion of press, as the rise of tabloid, confession, and true crime magazines enlisted readers’ help in solving crimes, each issue revealing a new detail in an ongoing case. “Increasingly newspapers were competing with the kind of true crime stories in those magazines,” James said. “The press was affected by the magazine boom, and they started to tell crime stories in ways that really got readers engaged—and coming back to buy the next day’s issue.” Media moguls spared no gory details; with queer sexual undertones, lurid descriptions, and an air of entertainment, readers countrywide held fast to their newspapers, armchair sleuths basking in the open arms of true crime.

“The crime stories concentrated so many of the period’s anxieties—about deviancy and normalcy, what constitutes the two, questions of justice, questions of the legal system and right and wrong.”While homosexuality was coded in many of these reports, and required Polchin to scrutinize hundreds of articles for clues of a queer subtext (where the murder happened, the relationship between killer and victim, how they met, the substance of the confession), the front-page crimes were often more explicit about the relationship between homosexuality and criminal acts. “To engage in homosexual acts was to commit a felony,” Polchin said, “so it just fit well with a whole set of criminal behaviors that the press was increasingly interested in emphasizing.” In the book, Polchin quotes the editor of the Green Bay Press-Gazette as he defends the use of sensationalized accounts of murder: “It must be printed, if public opinion is to be aroused to deal with this social menace…if printing the news means fanning the fire in some cases, it also furnishes the only method by which the fires can be controlled and restrained.”

Indecent Advances is structured to simulate the experience the public would have had encountering the crime at the time. “Each chapter starts with a sensational front page murder. Then there are questions and speculation about the crime, then there’s more follow up articles about the investigation, then there’s an arrest. If we’re lucky there’s a trial, and the trial is reported on,” James explained. And somehow, he manages to simulate the reading experience without recreating the sensational qualities of the original accounts. By acknowledging the over-dramatization and providing context around each particular crime, Indecent Advances tells the stories of men who, in search of connection, were killed. “I was heartbroken by so many of these stories, but the more I got into it, the more I felt committed to telling them, and particularly trying to get as much information as possible about the victims themselves, whose lives often weren’t discussed in the press,” Polchin said.

He hopes he doesn’t get weepy talking about these stories in front of people. “Even amidst all the dangers,” he said, “amidst all queer men had to protect themselves from, these crimes illuminate something about how men at the time found each other. As much as they show us the realities and the horrible tragic endings, there’s also a life happening before these crimes.”

***

Fifty years ago today, a police raid on the Stonewall Inn—a regular occurrence in which plainclothes officers overtook an establishment, lined up customers, checked identification, forced patrons dressed as women to verify their sex, and then arrested those who proved to be male—incited the riot that catapulted the LGBTQ movement. The violence unleashed over those six summer nights in 1969 was a response to the political consciousness that permeated the era, as well as a reaction to decades of injustice, injury, and criminalization.

The life of Lawrence Shead, like so many other queer men who were similarly murdered, was forgotten not long after his death. As assailants claimed “indecent advances,” shame engulfed families. Sons, brothers, fathers, and husbands went from victims to criminals. Shead’s killer went on to murder another man, Sheffield Clark, and when he was eventually caught, he pleaded insanity. To counter this claim, the prosecutor pointed to his verifiably sane response to Shead’s solicitations: “[Killing Shead] was what I might have done or you might have done under the circumstances,” he told the all-male jury. While the killer was eventually executed—deemed sane and calculated, a cold-blooded killer—Shead faded into history’s bygone pages, a queer criminal, a violent force. With Indecent Advances now in the world, a bit more honor has been restored to the lives of these men.