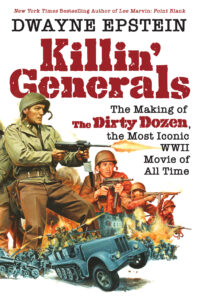

1967 saw the release of such recognized classics as Bonnie & Clyde, The Graduate, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner?, Cool Hand Luke, and In The Heat of the Night. However, the biggest box office success of the year was The Dirty Dozen. The premise of the two-and-a-half- hour film takes place during WWII when renegade Major John Reisman (Lee Marvin) is assigned to train 12 military prisoners convicted of violent crimes for a suicide mission behind enemy lines.

The film is structured in three parts; the recruitment of prisoners, their training, and the climatic mission. The result is an influential classic that resonates more than fifty years later and remains one of the biggest box-office hits in the history of MGM.

The film is certainly not the first of its kind to employ the concept of bad men doing good things. The premise was often used during the war itself and in several films since that predates The Dirty Dozen. Examples include All Through the Night (1942) and Passage to Marseille (1944), both starring Humphrey Bogart. What makes the Lee Marvin film so distinct from its predecessors is its level of both brutality and outright disregard for military protocol. Before The Dirty Dozen, maverick film characters eventually fall in line by the finale or the cause itself was vulcanized in its importance. Not so with The Dirty Dozen. They don’t care about the cause, only their own survival, despite the fact that to a man they are each a hardened criminal. Such a profound distinction outraged some critics at the time but had audiences cheering.

The legend behind its creation begins with, of all people, legendary sexploitation pioneer Russ Meyer. During the war, Meyer was a combat photographer and as such, took pictures of military prisoners in Europe he was told were trained for a suicide mission. He told their story years later to his neighbor, freelance journalist, E.M. Nathanson. The inspiration may have also come from a unit of the 101st Airborne nicknamed “The Filthy Fifteen” for its unsanitary habits and rowdy ways. However, following over two years of research and being unable to discover anything about the actual prisoners, Nathanson believed Meyer’s tale was a ‘latrine rumor’ and chose to fictionalize the account of the men and their mission. When The Dirty Dozen was published in 1965, it would eventually become a massive international bestseller.

The journey to the screen was thus set in motion. Prior to its publication, director Robert Aldrich attempted to buy the film rights but was outbid by MGM executives who purchased the rights in 1963 for the sum of $80,0000. Harry Denker was assigned to write the script for producing partners William Perlberg and George Seaton, who also planned to direct the project. Perlberg left the project first and was replaced by Kenneth Hyman, looking to follow up his similarly themed The Hill (1965). Seaton eventually dropped out as well due to scheduling conflicts. Nathanson consequently was appalled by Denker’s script and offered his own version. His script was also turned down. Oscar-nominated screenwriter Nunnally Johnson was assigned the task and the wheels were set in motion.

Almost simultaneously, Hyman went about casting the film, considering such actors as John Wayne, Aldo Ray, and Burt Lancaster for the lead role of Reisman. Other roles were mentioned for the likes of George Chakiris, Nick Adams, Jack Palance, and Sidney Poitier. Director Robert Aldrich came aboard to help with casting and brought in Lukas Heller to revise Johnson’s script. When John Wayne turned the part down for several reasons, Aldrich’s original choice of Lee Marvin was approved by MGM. One of the more interesting casting choices was actor/director John Cassavetes as prisoner Victor Franko. Cassavetes, who hated the script, had been blacklisted by producer Stanley Kramer and needed money to finish his current project. He eventually relented to Hyman’s demands resulting in a renaissance of the maverick filmmaker’s career.

Filming began in April of 1966 with cast and crew set to go to England for what was believed to be a few months of production. However, from the start, there were unforeseen problems. Costar Charles Bronson was mourning the recent death of his mother as well as the break-up of his marriage as he pursued Jill Ireland, wife of his good friend, actor David McCallum. His sullen demeanor earned him the nickname “Charlie Sunshine.” Leading man Lee Marvin was also in the midst of ending his marriage to Betty Marvin during the tumultuous relationship with Michele Triola, both of whom came to visit him on the location. The all-British crew frustrated director Aldrich for their slow way of working. The weather also proved to be a hindrance as constant rainfall held up the shooting schedule. Also not helping was the few days Marvin took off to go to California for the Academy Awards where he won the Oscar for Cat Ballou (1965).

Back in England, schedule and cost overruns continued, forcing the production to go into late October. In the interim, Cleveland Brown running back Jim Brown, making his second film appearance, was pressured to leave the film or risk a heavy fine from team owner, Art Modell. The ultimatum resulted in the 29-year-old Brown holding a press conference on location announcing his retirement from the NFL. The opposite took place for costar and popular singer Trini Lopez.

When he chose to take Frank Sinatra’s advice and ask for more money, Aldrich had Lopez’s character promptly killed off before the big finale.

Filming and finally post-production in the can, the movie had its world premiere in New York on June 15, 1967. The studio went all out to promote the multimillion-dollar production that resulted in decidedly mixed reviews. The NY Daily News gushed that it was “Possibly the most unique war drama ever filmed.” Bosley Crowther of the NY Times wrote, “A raw and preposterous glorification of criminal soldiers…A spirit of hooliganism that is brazenly anti-social, to say the least; a studied indulgence of sadism that is morbid and disgusting beyond words.” None of the reviews mattered as the film was an unqualified box-office sensation starting the now popular trend of summer box-office blockbusters. It eventually received four Oscar nominations and with its explosive finale winning for Best Sound. It should have received more, especially a nomination for Best Picture, as the timing of the film proved to be a perfect storm of events. The Vietnam War was escalating, massive demonstrations against it were growing and the Civil Rights Movement had exploded. Consequently, the film’s dark humor, violent content, and anti-authoritative and anti-military message struck a chord with audiences across all age groups and ethnicities.

Over the years the legacy of The Dirty Dozen has continued unabated. Its success allowed Robert Aldrich to buy his own studio and later revisit its anti-authority theme with the blockbuster smash The Longest Yard (1974). Lee Marvin was voted the number one male box office star and stayed in the top ten for several more years.

Charles Bronson stayed in Europe to make films and become an international superstar. The film careers of both Jim Brown and Donald Sutherland exploded as a direct result of their appearances in the film. Cassavetes now had the money to finish Faces (1968) and go on to make some of the most influential independent films in America. Writer E.M. Nathanson penned a successful Dirty Dozen sequel in 1987 entitled A Dirty Distant War. In 2001 the American Film Institute put the film on its list of “100 Most Thrilling American Films” at number 65. As recently as two years ago, a remake was announced by the same creators of Suicide Squad (2021), a film greatly influenced by The Dirty Dozen. It also influenced the likes of Quentin Tarantino as seen in his film Inglorious Basterds (2009), as well as Suicide Squad director James Gunn with his hugely successful franchise Guardians of the Galaxy (2014-2023).

When all is said and done, an over fifty-year-old movie can still maintain an enduring legacy for fans and filmmakers alike. The reason is deceptively simple. Any film that concludes with a main character witnessing the hypocrisy of the military establishment and then muttering, “Killin’ Generals can get to be a habit with me,” will last through the ages.

_______________________________

From KILLIN’ GENERALS: THE MAKING OF THE DIRTY DOZEN, THE MOST ICONIC WWII MOVIE OF ALL TIME, by Dwayne Epstein. Copyright ©2023 by Dwayne Epstein. Reprinted by permission of the publisher, Citadel Press. All rights reserved.

From KILLIN’ GENERALS: THE MAKING OF THE DIRTY DOZEN, THE MOST ICONIC WWII MOVIE OF ALL TIME, by Dwayne Epstein. Copyright ©2023 by Dwayne Epstein. Reprinted by permission of the publisher, Citadel Press. All rights reserved.