In January 1958, Elijah Muhammad sent a cablegram to Gamal Abdel Nasser, the president of the United Arab Republic, on the occasion of the Afro-Asian Peoples’ Solidarity Conference hosted by the Egyptian government in Cairo. Elijah, who had been taught by Master Fard that Blacks in America were an “Asiatic” race, had already formally endorsed Nasser’s seizure of the Suez Canal in public statements and his newspaper columns. In Nasser’s stand against the British, French, and Israelis, the Nation saw a reflection of its own fight against white supremacy in America. In his letter, Elijah wanted Nasser to recognize these parallels too.

“As-Salaam-Alikum.” He began the letter with the traditional Islamic greeting. “Freedom, justice, and equality for all Africans and Asians is of far-reaching importance,” he wrote, “not only to you of the East, but also to over 17,000,000 of your long-lost brothers of African-Asian descent here in the West.” He ended the letter with a prayer for “the unity and brotherhood among all our people which we all so eagerly desire.”

Nasser, fueled by the ideologies of Pan-Arabism and socialism, was no fan of religiously motivated Muslim activists. At home, he had already imprisoned leaders of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood whose vision of a modern Islamic state in post-colonial Egypt ran contrary to his own. In contrast to Elijah, who would appear in public wearing his trademark kufi African hat embroidered with a crescent moon and star, Nasser favored finely tailored suits and ties. Still, over the years, since the arrival of Malcolm on the scene, the Nation of Islam had gone from a fringe cult organization to one of the most influential—and fastest growing—African American organizations in the country, and it demanded to be taken seriously at home and abroad.

With its central message of economic self-reliance, the Nation had developed a vast network of business enterprises. In the mid-1950s, the Chicago temple had an associated grocery store, a restaurant, and a bakery, which employed a combined forty-five Muslims who served the large and fast-growing community. The Nation was constantly encouraging its members to start private businesses of their own, too. Elijah’s own wealth had ballooned to an estimated $1 million, not including his home and other real estate owned by the temple. His annual income, largely from donations from the dozen or so temples, as well as from profits from the Nation’s businesses, was approximately a quarter of a million dollars. For Black Muslims, the group’s numerous business enterprises and the wealth of their holy apostle were a point of pride. They signified both God’s favor for the movement and the Muslims’ ability to work together to improve the lives of Black Americans.

This newfound wealth and influence attracted the unwelcome attention of J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI. Hoover had built the FBI from the ground up and had been the chief of the bureau since 1924. In the decade since the end of World War II, the FBI had doubled in size to nearly seven thousand agents. The zealous new recruits, encouraged by their rabid boss, saw enemies everywhere. Any individuals or organizations that exhibited potential to subvert the American government quickly fell into the FBI’s crosshairs. The Nation of Islam, with its strong emphasis on community, separatism, and Black supremacy, was an obvious target for surveillance.

The FBI circulated its first major internal report on the Nation in 1955, soon after Khaalis, soon after Hamaas Abdul Khaalis, the promising young prospect from the Harlem Temple sent by Malcolm X, arrived in Chicago to begin his work at the headquarters. The report, nearly one hundred pages long, described the Nation of Islam as a “fanatic negro organization,” an “especially anti-American and violent cult.” The monograph, distributed to all the bureau’s major field offices, was mandatory reading for all field agents in cities where the Nation of Islam had a significant presence. The report explored the murky history of Wallace D. Fard, known as Master Fard Muhammad by adherents, noting that he had once told the Detroit police that he was “the Supreme Ruler of the Universe.” It also dedicated several pages to Elijah Muhammad and the story of his ascension from humble disciple to absolute ruler and holy apostle of the Black Muslims.

Most of the report detailed the sprawling and complex structure of the Nation. The Nation’s temples were concentrated in the Midwest and Northeast at the time, with one in San Diego. Each temple had a minister, who oversaw religious matters. A secretary under each minister took care of day-to-day operations of the temple. The Fruit of Islam, modeled after the muftis of the progenitor Moorish Science Temple organization, was a paramilitary force of men who trained in martial arts and combat at most of the Nation’s temples under the supervision of a captain. The captains of each unit of the Fruit reported directly to a supreme captain in Chicago who answered directly to the messenger Elijah. The women, meanwhile, trained in homemaking, cooking, and sewing, and in doctrines and theories of the Nation’s theology. The children of the members were encouraged to attend the University of Islam for schooling wherever one was available.

By the time Elijah sent his letter to Nasser in early 1958, Khaalis had already shot up through the ranks of the Nation to become the secretary of Temple No. 2, the de facto national secretary of the Nation of Islam, in charge of operations across the country. Khaalis, now in his mid-thirties, fit more snugly into his suits, and he lived with Ruby and the two children, Ernest Jr. and Eva, in an apartment inside the Nation’s Chicago compound in the Hyde Park neighborhood.

The FBI had started tracking Khaalis when he was still at Temple No. 7 in Harlem. Months before he left for Chicago, two special agents of the bureau found a pretext to interview him about his role in the organization. Khaalis did not make a good first impression. In a memo to Hoover, the special agents reported that Khaalis “manifested a belligerent and hostile attitude” and “an open and great hatred towards all members of the white race.” Khaalis told the agent that he had been Muslim his whole life and “his leader is Allah and the Prophet Elijah Muhammad.” Khaalis complained that the United States had “denied him and members of his race their rights of citizenship, their freedom, justice and equality.” Months after that encounter, the FBI added Khaalis to the notorious Security Index.

As secretary of Temple No. 2, Khaalis became one of Elijah’s closest and most trusted aides, answering directly to the messenger. Elijah trusted Khaalis to make his personal travel arrangements to visit temples around the country. Some in the Nation also believed that Khaalis was the person actually writing Elijah Muhammad’s weekly column, “Mr. Muhammad Speaks,” in the Pittsburgh Courier, the leading African American newspaper in the United States. At the weekly Sunday congregation at Temple No. 2, Khaalis would often rise after the messenger had finished addressing the faithful to make his own announcements about the affairs of the university, fundraising efforts, and other mundane organizational matters. As he became more deeply embedded in the organization, though, he began touching on more sensitive topics. An FBI mole reported that in a meeting on May 22, 1957, for example, Khaalis stood up and began railing against the FBI, which, he told the gathered members of the Nation, was infiltrating the ranks of the organization. He might have struck some as overly paranoid.

Soon, the messenger began inviting Khaalis for dinner at the family home, a privilege reserved for only the most elite and trusted members of the Nation. At the dinner table, in the company of Elijah’s immediate family, Khaalis dwelled on potential threats lurking in and around the organization. On one occasion, he suggested that the entire headquarters required new security measures. He suggested introducing background checks for new members. At another dinner table conversation, also reported to the FBI, he began rattling off names of people he thought should be turned away from the Nation of Islam because he suspected them of being informants.

His obsessive focus on potential threats put Khaalis on a collision course with Raymond Sharrieff, the supreme captain of the Fruit of Islam, responsible for the entire organization’s security. Sharrieff was a few years older than Khaalis, broadly built, with eyes that always appeared to be scanning. Unfortunately for Khaalis, Sharrieff was married to Ethel, Elijah’s eldest daughter. He was one of the most influential people in Elijah’s close orbit. Many in the messenger’s family were already wary of Khaalis, just as they were of any outsider who got too close to Elijah, even Malcolm. When Khaalis began butting heads with Sharrieff, the entire family quickly turned on him.

The spats stemmed mostly from the overlapping responsibilities. Once, for example, Khaalis spotted one of the Fruit of Islam soldiers vacating his post during a public meeting, leaving a stash of weapons unguarded. Khaalis demanded an apology, but Sharrieff refused to let the soldier give him one. The tensions would occasionally spill out at the dinner table when both men were present. Elijah was forced to mediate, and it began to wear on him. Elijah complained to others that Khaalis did not know his place.

It all ended spectacularly, one evening in September 1958. Khaalis had been invited to sit in on a trial administered by the Fruit at the Nation’s headquarters. A sister named Thelma who worked for Khaalis at the University of Islam had been accused of writing letters in which she had criticized one of Elijah Muhammad’s daughters, Lottie, for interfering with the workings of the university. Criticizing one of the members of the messenger’s family was a grave offense and not something Elijah allowed. Elijah had decided to adjudicate the trial himself.

The proceeding went on as anyone might have predicted. Elijah appeared intent on defending his daughter no matter the facts presented by the other woman. As Khaalis watched, he understood that the sister from the school never had a chance at getting justice. Khaalis had always had a hard time biting his tongue when he saw something being done incorrectly. Elijah was about to announce a punishment when Khaalis suddenly stood up and began shouting in defense of the convicted woman. Muhammad’s daughter, Khaalis yelled, was clearly interfering. The accused woman had done nothing wrong.

Khaalis and Sharrieff had already had a run-in earlier in the day in Elijah’s presence, and the messenger had little patience for Khaalis. He exploded from the bench, telling Khaalis that he had crossed a line, and commanded him to apologize to his daughter on the spot. Khaalis stood silently. Raymond Sharrieff suddenly lunged at Khaalis, and the two men tumbled to the ground, grappling, throwing punches, and yelling obscenities. Members of the Fruit jumped into the scuffle, finally separating the two men and removing them from the courtroom.

A few days later, Khaalis submitted his resignation to Elijah Muhammad. He knew that excommunication awaited him anyhow. As Khaalis and Ruby packed up the apartment and prepared to leave the compound, he warned other members that the Nation had become a self-serving family oligarchy. He had been at the family dinner table, and he had come to believe that it was corrupt to the core. Elijah Muhammad, meanwhile, regaled his new dinner guests with stories about the time that Khaalis had spent in the “nut house.”

Khaalis and the family checked into a hotel in Chicago. Khaalis could not shake the feeling, though, that they were being followed. Wherever he went, he saw men that he recognized from the ranks of the Fruit. Finally, in December 1958, four years after he had arrived to serve one of the most important and powerful African American leaders in the country, Khaalis returned to New York City. The family had nothing, so they moved in with Ruby’s parents at their new home in the borough of Queens.

In the summer of 1959, the Nation finally broke into the national consciousness of America through a five-part public television documentary series titled The Hate That Hate Produced. The series, hosted by journalist Mike Wallace, and reported by a young Black journalist named Louis Lomax, raised the alarm about the threat posed to America by the Nation of Islam. “These homegrown negro American Muslims are the most powerful of the Black Supremacist groups,” Wallace said in his introduction. The Nation, he explained, “now claimed a membership of a quarter of a million Negros.” Millions of Americans watched and were shocked by the images of young Black men from the Fruit of Islam training in martial arts overlaid with the audio of Elijah Muhammad’s speeches denouncing the “devil” white race as the ultimate enemy. Elijah Muhammad was introduced a little more than four minutes into the first episode when a black-and-white photograph appeared on the screen. “Here you see Manhattan Borough President Hulan Jack shaking hands with Elijah Muhammad the leader of the Muslims,” Wallace said. In the photo, two other men stood by Elijah’s side as he greeted the politician. On his immediate left was Malcolm X, and next to Malcolm stood Khaalis, Minister Ernest X.

The two men could not have ended up further apart. Khaalis was once again delivering mail for the USPS, and the FBI had removed his name from the Security Index soon after he left Chicago. Malcolm, meanwhile, was the undoubted breakout star of the documentary. In the months that followed, he regularly appeared on television to debate prominent figures, and he began touring the country on a speaking circuit. The Nation reaped the rewards. Membership doubled to sixty thousand people in the weeks after the series aired. It became the largest organized Muslim group to have existed in America, and, in the midst of the civil rights movement, one of the largest and most important groups of African Americans in the country. When the first episode aired, Malcolm was traveling through Africa and the Middle East as Elijah’s emissary meeting many important world leaders, including Gamal Nasser’s deputy and future Egyptian president, Anwar Sadat.

At the 1959 annual Saviours’ Day convention, when the Nation celebrated the birth of Master Fard, Elijah finally received the message that he had been anticipating for almost two years. A leader of a Pan-African organization took the stage and read a letter addressed to the “brother peoples” in the Nation of Islam from the President of Egypt, Gamal Abdul Nasser.

“Unity and solidarity are the two indispensable factors for realizing our liberty,” Nasser wrote in his message to the Black Muslims. “This lesson must be seriously taken to heart and maintained against imperialist forces seeking to undermine our integrity and convert us into disintegrated groups which can easily be victimized and made to serve their selfish interests.” Islam, “our great religion and traditions and ways of living,” Nasser concluded, “will serve as the cornerstone in building the new society based on right, justice and equality.”

___________________________________

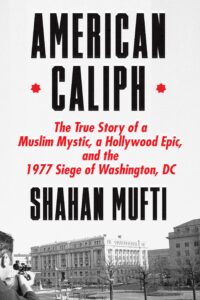

Excerpted from American Caliph The True Story of a Muslim Mystic, a Hollywood Epic, and the 1977 Siege of Washington, DC by Shahan Mufti. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, November 2022. Copyright © 2022 by Shahan Mufti. All rights reserved.

–Featured image: Men at Saviours Day, 1974. John H. White, 1945-, Photographer (NARA record: 4002141) – U.S. National Archives and Records Administration