But the man had hereditary tendencies of the most diabolical kind. A criminal strain ran in his blood, which, instead of being modified, was increased and rendered infinitely more dangerous by his extraordinary mental powers. Dark rumours gathered round him in the university town, and eventually he was compelled to resign his Chair and to come down to London. He is the Napoleon of crime, Watson. He is the organizer of half that is evil and of nearly all that is undetected in this great city. He is a genius, a philosopher, an abstract thinker. He has a brain of the first order.

Article continues after advertisement

— Sherlock Holmes describing Professor James Moriarty in “The Final Problem”

This is a story about feces.

No, scratch that. “Feces” is too formal. Like something you might hear at your doctor’s office. This is a story about dung. Nope. That doesn’t work either. Too zoological. Going number 2? For God’s sake, I have a PhD. Crap. Defecation. Excrement. Manure. Stool. Waste. Droppings. Meadow muffins. Night soil. Pasture paddies. Prairie pancakes.

Fine. I give up. This is a story about poop. Goat poop. Specifically, synthetic goat poop.

And a lot of it.

***

Stanley Lovell was a chemist, and a very good one. Like many patriotic Americans, he signed up to contribute when the United States joined the Second World War. His talents and skills were immediately recognized by Dr. Vannevar Bush, the director of an American wartime agency known as the National Defense Research Committee (NDRC), who assigned Lovell to help the Quartermaster Corps design innovative chemical solutions to common military problems posed by a truly global war. Some of these would include how to make grommets (like an eyelet on a shoe or tarp) out of plastic instead of metal (to save the metal for other uses); or how to make mold-proof tents, shoes, leggings, (etc.), which are particularly necessary in Pacific jungle environments; or to figure out a way to make ponchos suitable for desert warfare, where it can be frigidly cold in the night, but blazing hot during the day.

This was immensely important work. It would help to win the war. Lovell was making a contribution.

But he was bored. Fortunately for him, this boredom did not last long. Dr. Bush was now helping to recruit scientists for another organization. A secret one. Full of spies—and the people who would develop the technology to help those spies win the war. One day, Bush came to his new employees with a seemingly simple thought experiment:

You are about to land at dead of night in a rubber raft on a German-held coast. Your mission is to destroy a vital enemy wireless installation that is defended by armed guards, dogs and searchlights. You can have with you any one weapon you can imagine. Describe that weapon.

Lovell couldn’t just say “tactical nuclear weapon” (which would be my knee-jerk reaction if asked that question today, but alas, they hadn’t been invented yet), so he spent about a week concocting his answer. His response hinted at his future aptitude for dirty wiles and clandestine shenanigans. He submitted:

I want a completely silent, flashless gun—a Colt automatic or submachine gun—or both [technically this would be cheating— Bush said one weapon]. I can pick off the first sentry with no sound or flash to explain his collapse, so the next sentry will come to him instead of sounding an alarm. Then, one by one, I’ll pick them off and command the wireless station.

Quite devious for a chemist. And it was enough to get Bush’s attention. Shortly afterward, Lovell was told to report to an address in Northwest Washington. It was there that he first met William “Wild Bill” Donovan: lawyer, politician, the most decorated soldier in American history, and the director of the newly formed intelligence agency the Office of Strategic Services (OSS).

Donovan kept it simple: “You know your Sherlock Holmes, of course,” he said. “Professor Moriarty is the man I want for my staff here at OSS. I think you’re it.”

Donovan kept it simple: “You know your Sherlock Holmes, of course,” he said. “Professor Moriarty is the man I want for my staff here at OSS. I think you’re it.”

Donovan continued, “I need every subtle device and every under-handed trick to use against the Germans and the Japanese—by our own people—but especially by the underground resistance groups in all occupied countries. You will have to invent all of them, Lovell, because you are going to be my man.” As Lovell described in his memoir, Donovan was really telling him, “Throw all your normal law-abiding concepts out the window. Here’s a chance to raise merry hell. Come, help me raise it.”

Lovell had found his war. He was in.

***

Bill Donovan was a firm believer in the power of science to help win the war. He thought the side that most effectively and efficiently applied science and technology to intelligence and combat operations would have the decisive edge. As a result, in October 1942, only four months after the creation of the OSS, Donovan formed the OSS Research & Development unit (OSS/ R&D), and put Lovell in charge. OSS/ R&D had a number of responsibilities: camouflage; chemical, mechanical, and electrical implements; documentation forgery; disguise; drugs, toxins, and lethal weapons; secret writing; chemical and biological warfare defense . . . and offense. And of course, special weapons and devices— the devious spy gadgets that are so alluring to our visitors at the Spy Museum.

Like the OSS writ large, the OSS/ R&D unit had some smashing successes . . . and some dismal failures.

Some of the lowlights:

1. A cat bomb, based on the undisputed premises that (a) cats always land on their feet and (b) hate water. The plan was to hang a poor kitty in a harness from the bottom of a bomb, with some kind of device that allowed said kitty’s movements to guide the bomb as it fell. If you dropped it in the vicinity of a naval target (such as a German battleship), then the cat’s natural instinct would be to think, “Holy hell, I’m falling into water. I hate water, so let’s try to land somewhere dry. Like that German battleship over yonder.” And then BOOM. Suicide kitty is a martyr to the cause. Of course, this was a ridiculous idea. During experimentation, the test cat became unconscious (and thus ineffective) during the first fifty feet of the fall. We don’t actually know if the harness/ steering apparatus would have worked, since the cat passed out before that technology could be fully vetted.

2. The OSS learned that Hitler and Mussolini would be holding a war conference at the Brenner Pass, located in the Alps between Italy and Austria. Lovell proposed an “attack which they cannot anticipate.” He was probably right—they couldn’t have seen this one coming. Lovell’s plan called for smuggling in a vase of cut flowers to be placed on the table between Hitler and Mussolini. In the vase’s water would be an odorless, colorless chemical derivative, which would seep into the two tyrants via their eyeballs. Hitler and Mussolini (and anyone else in that room) would be permanently blinded as the chemical atrophied the optic nerve, rendering it irreversibly nonfunctional. But that was only part one of the plan, and it’s surprisingly the less absurd part. Part two required the assistance of the pope—despite the Vatican being officially neutral during the war—who would issue a papal bull stating that God himself had smitten the two leaders for their evil ways. The OSS was now asking the pope to lie. Yet for Lovell, this would be justifiable: In one action, the pope could stop the war, and would be “advancing the cause of Christianity more than any man on earth.” Okay. Maybe. Unfortunately for Lovell (but fortunately for the immaculate reputation of the Church), the plan fell apart when the war summit was moved to Hitler’s private railway car, surrounded by some of his best troops. The OSS was good, but not that good.

3. Working from their quaintly old-fashioned—and completely ridiculous—views of gender stereotypes, Lovell and his team saw Hitler’s penchant for violent mood swings and poor emotional control as evidence that he was “definitely close to the male-female line.” The plan involved spiking his food with female hormones, to push him over the gender edge, making his mustache fall out and his voice turn soprano. They even supplied one of his gardeners with the drugs and a satchel full of money as payment for the operation. Apparently it didn’t work—or perhaps more likely, the gardener took your tax dollars and then threw the drugs in the trash.

4. Another plan called for arming Chinese call girls with poisons or toxins to use against high-ranking Japanese officers who utilized their services. Simple enough, right? The catch was that the poison’s delivery system needed to be just about invisible, since these women didn’t have the means to conceal anything in what they were(n’t) wearing. Odds are, you can probably figure on your own how they solved that problem . . . And then the weapon, which was based on the highly lethal botulism toxin (fun fact: so is Botox!) was successfully smuggled into Japanese-occupied China. But nothing happened. No high-level Japanese officers were killed, and the OSS was baffled as to why. Only later would they learn that their OSS contacts in Asia, performing their due diligence, decided to test the botulism on donkeys before giving it to the Chinese prostitutes. To their dismay, the weapon didn’t work. The donkeys survived (and in fact, seemed completely oblivious that they’d been poisoned), so the OSS contacts in Asia assumed the weapon was ineffective and scrapped the mission. What they didn’t know: Botulism is so lethal it will kill the living bejesus out of almost everything on earth . . . except for donkeys, which are one of the few living creatures immune to the toxin. Whoops.

These are just some of the unusual hijinks of the OSS/ R& D unit. But the crème de la crème of unconsummated insanity was an operation known as “Capricious.” For Stanley Lovell, this was the high point of his time as the OSS’s Professor Moriarty.

***

It’s interesting to think that in a war in which tens of millions of people were killed in almost every manner possible—conventional munitions, disease, starvation, genocide, civilian and military purges, and, of course, atomic bombs—nations would be hesitant to use a type of weapon because they thought it wasn’t ethical. And although the United States formed a committee to research the utility of biological pathogens in the war (the Merck Committee, named after its chairman, Dr. George Merck, president of Merck and Company), there was little appetite among the American leadership to go beyond the casual “thinking about things” phase. President Roosevelt was vehemently opposed to the use of germ warfare, and military leaders such as George Marshall and Bill Donovan thought it was an immoral way to fight a war (bullets and bombs only, like God intended). The normally composed and erudite Vannevar Bush was known to say all manner of unspeakable things any time the topic was raised.

As long as the war was going well, biological weapons were off the table. Any conversation about their use was a nonstarter. Any longterm planning for their production was a waste of time. They were simply not to be.

As long as the war was going well. There are shelves full of books that delve into the war in North Africa between Allied forces and German general Erwin Rommel. There are also a lot of documentaries about Operation Torch and the battle of Kasserine Pass (in case this book fills your reading quota for the year). Maybe you can find one on the History Channel at 2 a.m., after a marathon of Ice Road Truckers, Pawn Stars, or Ancient Aliens. In any case, I won’t spend a lot of time rehashing that history here. All you really need to know is this: In November 1942, America got its first taste of combat against the Germans. And America got thwacked. It was a bitter pill to take, and a sense of panic began to set in throughout the corridors of the Pentagon. Thousands of American soldiers were killed, wounded, or missing; hundreds of vehicles were destroyed; and there were abject failures at every measurable level of military metrics—command, training, logistics, air support, joint operations, combined arms. Even things as seemingly simple as basic map reading were apparently too onerous for America’s green troops (and their just as green commanders).

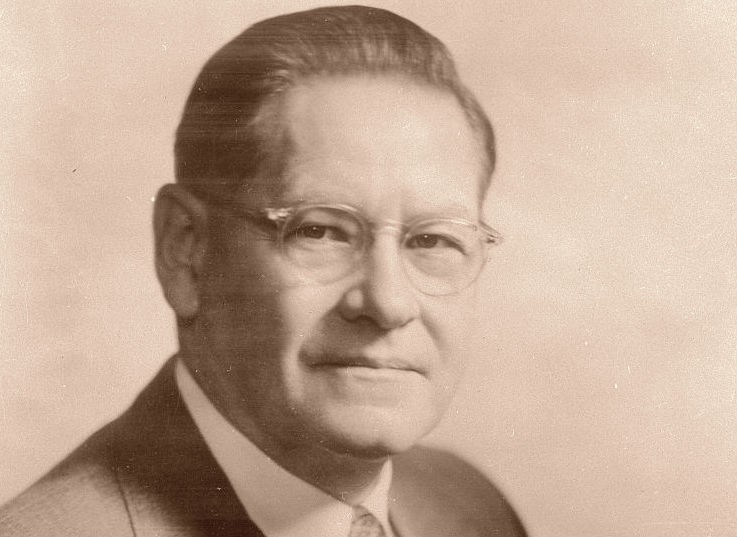

Stanley Lovell

Stanley Lovell

Adding injury to injury, the OSS officers in Morocco were reporting that large numbers of Germany’s best and most battle-tested troops were flooding into Spanish Morocco. Francisco Franco’s Spain was nominally neutral, but he was a fascist and highly sympathetic to the Axis cause. Clearly these German troops were entering Morocco with the consent—and maybe even the cooperation—of Franco’s government. This could be a frightening omen for things to come. What if Spain formally joined the Axis? Spanish Morocco could become a staging point for hundreds of thousands of German troops, who could then cut off the vital supply lines to Allied forces who were trying (perhaps now in vain) to dislodge Germany from the African continent.

Something drastic had to be done, and so they turned to Lovell, their evil genius. Now that the handcuffs were off, germ warfare could be the answer to the Allies’ problems in North Africa.

***

Stanley Lovell’s mission was to execute the perfect covert action: a germ warfare attack against the Germans in North Africa without their knowing what hit them. This was more than a desire to be sneaky. It was important to the Allies to maintain the moral high ground in the war, and to prevent the Germans from retaliating with their own biological attack.

One key aspect would be to employ a less-than-lethal strain of biological agent. The idea wasn’t to kill all the Germans in the region—just to make them all wish they were dead. Hordes of sick soldiers might be chalked up to just bad luck; thousands of dead Germans, and someone is going to be asking questions. Imagine the worst stomach flu you’ve ever had . . . then multiply that by an order of magnitude. According to Lovell, the germ cocktail OSS created contained “an assortment of bacteria from tularemia and psittacosis to all the pests known to the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse.” This would bring the German war machine in Spanish Morocco to a standstill. And when the troops came back, they’d be significantly demoralized.

Lovell set out to finalize his plans. His research of the region had uncovered several important facts:

- There were more goats than people in Morocco.

- Moroccan goats pooped. A lot.

- There were also a ridiculous number of flies in North Africa. In the summer, they were everywhere in Spanish Morocco.

- North African flies were particularly pesky. They flocked to the moisture from the eyes, noses, and mouths of humans.

- Flies regurgitate what they’ve previously eaten when new food comes their way.

Each of these independently is a random fact. But taken together they crafted a recipe for a perfect germ warfare operation. If Lovell could lace the poop with biotoxins, the flies would provide the perfect vector to incapacitate the German army in Spanish Morocco.

But how do you guarantee the flies will be attracted to your particular brand of biotoxin-laced goat poop? The OSS wasn’t going to leave this up to chance—Lovell had the answer. They would manufacture a synthetic variant of goat poop, with a pull so powerful that it would never fail to bring the flies home to roost (to mix about five metaphors). The chemical attractant was apparently so powerful it would wake North African flies out of hibernation. It’s like the sweet aroma of a local bakery, a newborn baby, or freshly cut grass—but with poop.

The only challenge that remained was to figure out how to deliver the synthetic goat poop to Spanish Morocco without being observed—to keep the covert in the covert action. After some brainstorming, Lovell decided that the only way to secretly introduce their concoction into the region was via airdrop.

It was then that one member of Lovell’s team spoke up and identified a major kink in this plan. Most of the houses in Spanish Morocco have flat roofs. A whole lot of the goat poop would end up dropped on the roofs, and unless the OSS was also planning on developing a new genetically engineered variant of flying goat, it would be hard to explain how the poop got on the roof. Lovell pondered this problem, but had to concede this was a valid point. He finally responded, “The orders are to take out Spanish Morocco when ordered to do so, and if we do there’ll be mighty few people inspecting rooftops.” He, too, had a valid point.

Fortunately, the progress of the war intervened before Lovell could test his theory—and his synthetic poop. In the midst of development and testing, the OSS learned that the Germans were completely pulling their troops out of Spanish Morocco and redeploying them to the Eastern Front, to reinforce the effort to capture the Soviet city of Stalingrad. Hitler’s ill- fated obsession with taking the city named after his nemesis saved the OSS, and by extension the United States, from being the only nation in the European Theater of World War II to resort to biological warfare.

***

From NUKING THE MOON by Vince Houghton, published by Penguin Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2019 by Vincent Houghton.