With Bridgerton Season 3 hitting our screens and as we prepare to drop everything to binge-watch Lady Whistledown’s love story, it’s worth noting what the show has done to our period dramas and just how far we’ve come —no pun intended.

Before Shonda Rhimes’s first season thrilled our nerves and tore our expectations to shreds, we were used to the sedate, even polite, pacing of Downton Abbey where illicit sex was heavily frowned upon and women had orgasms strictly off-screen.

Bridgerton arrived like a wild thunderstorm on a spring day, just when we were reeling from prolonged lockdowns and social isolation, and turned everything we knew on its head. Here was Daphne Bridgerton exploring her sexual desires, having multiple orgasms, and seemingly having a bloody good time in bed.

Season 2 was one of delayed gratification, but in the end, it didn’t wait for Kate and Anthony to be sedately married, and we were witness to some hot outdoor sex and some interesting Regency undergarments being slowly peeled off.

A Note on Regency Clothing

How much clothing would need to be taken off for historical sex? Well, Regency clothing didn’t have the problems of the Victorian tight corset, or multiple laces and hoops. Instead of a tight corset that a Victorian woman may be suffocating in, Regency women would have worn stays – light, cotton garments that showed off the boobs and were comfortable to wear. So, to get down to the action, you might have to work your way through a coat or tightly-buttoned jacket, a hat (bonnet or cap) without messing up the hair. And gloves and shoes. And that’s just the outer garments. Then make your way through an empire-style dress with a high waist but without the multiple hoops and bustles of other time periods, a petticoat or two, stockings, and then the stays worn over a chemise! So, in short, a lot of clothing!

As we lap up Season 3, let’s look at some assumptions about women and sex that haunt our period fiction and take a peek at what some authors like to do about it.

Assumption One: Women simply do not have sex, my dears

If we read and watch the court presentations, tea dances, Almack’s strictly-gatekept balls of usual Regency fiction, we may be forgiven for thinking that women in the Regency period thought only about ball gowns and marriage prospects and that their body was an untouched landscape.

I worry that if we devour a genre now, in today’s day and age, and we gobble up repressive tropes about women and sex, we are in danger of sticking with and perpetuating these tropes today. Olivia Petter says in her article Mind the Pleasure Gap that young girls are taught about the dangers of sex—unwanted pregnancies and diseases—and not about healthy desire or how to explore it. She says, “A new survey has shown that two in three women are doing things during sex that they don’t enjoy” and are reluctant to ask a partner to stop. To me, fiction, even historical fiction, has a responsibility to show a more sex-positive view of women and women’s bodies.

I’m also glad for the novels that explore queer relationships, including the witty and wonderful novels by Olivia Waite and Marianne Ratcliffe, as this allows us to give our leading ladies a more diverse and varied sex life.

Assumption Two: Men sow their wild oats before they get married, but women remain untouched virgins

This is a scary vision of what society expected of women, but also the pressures women continue to feel to keep their sexual desires private or unexplored today. When we are introduced to a woman and man in period fiction, we are ubiquitously told that the man has lived a varied and vigorous sexual life, whereas the woman has been brought up strictly and is a virgin.

Lisa Kleypas plays with this by moving outside the realms of the ton and the marriage mart and making her heroines seamstresses and actresses with an independent life.

Bea Koch reminds us, “Regency history [is full of] heroines who break the mold…” She not only writes about the artistic endeavours and scientific pastimes of the Regency’s famous real-life women, but each woman also comes with her list of known lovers. Koch says, “In truth, a lot of the sex happening during the Regency was firmly outside the bonds of marriage.”

The interesting thing about the Regency period is that not only was it okay for a woman to have a screaming good time in her marital bed, it was also trop de jour that upper class women may take a lover or two. Many Regency authors cover this up with today’s relatively repressive sexual mores and don’t talk about a woman’s multiple lovers, but in my next book, An Unladylike Secret, a supporting character, Lucretia Underwood, openly – and hilariously – talks about wanting multiple lovers.

Assumption Three: If they do have sex before they are married, there is a darned good reason for it that has nothing to do with a woman’s sexual desires

There are many examples of period fiction where if a woman has had sex before her love interest awakens her to its wonders, then there is a jolly good reason for this. Maybe she was sexually exploited. Maybe she was forced into prostitution and/or was a kept mistress. Sex for the sake of sex and desire are not as easily explored.

While some of Mary Balogh’s stories also follow these tropes, what I admire about her work is that she allows her heroes and heroines to explore their sexual desires and focus on sexual desire as something important in its own right.

When I wrote my first Regency novel, Unladylike Lessons in Love, one of my editors asked me, “Is Lila a virgin before she meets Ivor?” My other editor responded, “I think she seems quite sexually aware.” My response: I refuse to ask my heroines if they are virgins or not.

Assumption Four: When they do have sex, women wait demurely for it to be after they fall in love

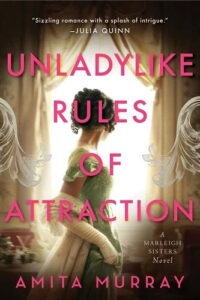

Men are unabashedly not held to this standard in Regency fiction. In fact, it is a show of virility to say that the leading man has had liaisons. But even when writing the main love story, we are supposed to help the couple fall in love first. In my second Marleigh sisters novel, Unladylike Rules of Attraction, there is a powerful attraction between Anya and Damian. We see their physical attraction to each other and their vigorous banter and palpable tension. Things get steamy under the bedsheets before they fall in love. (I lie. The action is in a garden and not under the bedsheets at all.)

Tessa Dare pushes against this prevailing trope by giving her heroines an independent life and strong ideals, so that by the time they meet their love interest, they often fall in lust first and explore this before they fall in love.

Assumption Five: Good women have sex in a strictly missionary position

There is of course the memorable vertical scene in the first season of Bridgerton. I have a scene on a table in Unladylike Lessons, and my leading ladies like to sometimes lead in the bedroom too and, at times, tend to be on top of things, if you know what I mean.

A few tips for sex in historical fiction:

–Make full use of the fact that Regency clothing does not come off fast! Instead of speeding through that bit, can it be built into the action?

–Use the repressive tropes to your advantage by letting the heroine fight against them and assert her agency. The tropes can also help in delaying gratification and letting romance build slower.

–Use the sex not just to do a few swoony scenes but also to develop the emotional relationship between the people involved

–Do your characters talk during sex and can you use this to develop the story?

–Let the characters learn more about themselves through their sex life. Make sure they’re growing as people, growing in how they see each other and how much they like each other

–Can you name body parts instead using overdone euphemisms? Were there any interesting names (and props!) used in your chosen historical time period?

–Whatever your ideals about sex – consent, female agency, pleasure, paying attention to one another – show them to us through the action.

–But, my dears, mostly, enjoy!

***