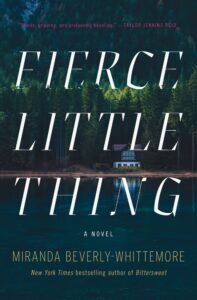

Place has always been important in the books I write. My new novel, a literary psychological thriller called Fierce Little Thing, is set on a back-to-the-land commune-turned-cult in rural Maine, where a group of children are driven to a terrible, desperate act in a last-ditch attempt to save the only home they’ve ever loved. More than two decades later, the same group of five middle-aged friends are blackmailed back together and onto the land, forced to reconcile how what they did has shaped who they are, and who they will become.

I’ve set my three most recent books in fictionalized versions of places I know well. My New York Times bestseller Bittersweet—about a naïve Little Red Riding Hood who becomes a conquering Big Bad Wolf—is set at a verdant, isolated Vermont lakeside estate called Winloch, based on a piece of land where I’ve been going ever since I was a child. June—about a secret Hollywood love affair in the Midwest—is set in a haunted, decrepit mansion in small Ohio town, based on a home my grandmother spent time in when she was a little girl (the family who owns it a century later even let me come hang out for a week, armed with a measuring tape and camera, so I could get every detail right). And the commune in Fierce Little Thing, called Home, is set at an imagined version of a lake I first went to in my late teens, where the family of my then college sweetheart (now husband) has owned land for decades. It’s a beautiful, peaceful spot. I’ve spent many long, luscious summer days lolling in the hammock and exploring in a kayak. But if knowing all of these places very well made it easier to capture on the page, loving them, if anything, made it much harder. It’s a challenge to turn beloved spots into the settings of novels where some pretty wretched things occur.

But just as I’m never ready to start drafting a book until I knew a whole lot about my characters’ dreams, needs, and physical characteristics, I’ve learned I simply can’t write about a place until I know it well. I have to know what the world of the book sounds like when it rains, what trees and plants grow there, and which populations of birds and insects they support. I must know what it smells like on a hot day, and what the place remembers. Understanding setting in this deep way doesn’t just make a novel more believable; it’s another way to build tension, which is the propulsive engine of forward momentum. That is to say, I’ve discovered that knowing a place inside and out means I can write a page-turner about it.

I’ve written more than one book about murder, grief, and long-buried secrets set in places I know and love…Now that I’ve written more than one book about murder, grief, and long-buried secrets set in places I know and love, I’ve discovered a few tricks to encourage this transformation—from my happy, lived experience to what my characters go through while on that same land. The first trick lies in harnessing the intimacies of a place—especially when the natural world is involved—to illustrate the darker parts of the tale.

Saskia, the narrator of Fierce Little Thing, first arrives at Home from New York when she’s twelve. She’s enchanted by a place so redolent with nature, and by the fact that the isolation of Home allows her to be cut off from the outside world; she has her own reasons for being glad to be cut off. The day Saskia arrives, she explores, observing, “Wind ruffled the trees and groundcover relentlessly. I saw, now, that there was as much movement as in the city, only here it wasn’t cabs and bikes and buses; this was a living thrum in a language I didn’t yet speak.”

But much later, after Saskia knows far more about the realities of how Home operates, and what it demands of her, she moves through that same forest: “The ghost-white trunks of the Batula papyrifera groaned. White crystals whipped into my eyes and my breath clouded the air. In the biting chill, away from the others, I tossed the hatchet, my eye on a knot. It hit its mark without a shred of doubt.”

Those two sections illustrate Saskia’s change as a character, and how her relationship with Home has transformed as well. By that second passage, she’s no longer enchanted by the glimmering unknown; she understands all too well the particulars of that wilderness’s brutal, physical demands. In fact, she knows so much that she refers to the paper birch by its Latin name, and has become so skilled in the ways of life there that she can effortlessly aim a hatchet into the knot of a tree. In other words, she has become an expert on Home, for better or worse, developing an intimate, unhealthy connection with the land just as she might with another character.

The weather has changed too—by that second passage, we’re no longer in the dappled sunshine of a June afternoon. Weather is another powerful way to increase tension. The seductiveness of water lapping in a cove on a gorgeous summer afternoon becomes something much more threatening when a thunderstorm moves in overhead (as happens in a pivotal scene in Bittersweet), just as the endeavor to live year round without electricity on a tract of Maine land takes on a new reality when a reader finds their main character in the dead of winter. Seasonal changes are inevitable in many places in the world, which can offer a gift to readers who’ve been marking a book’s turn from sunny skies to storm clouds. Bringing on a snowstorm or the sound of rolling thunder signals to a reader that the good, dark stuff is coming; those moments when someone like Saskia must prove what she’s made of, because the world won’t allow her any other choice.

Finally, in addition to offering grounding, the daily habits of a place can provide a metaphorical drive to the story. In Fierce Little Thing, the wail of the loons out on the lake haunt Home’s nights, a cyclical, lonely sound that marks Saskia’s journey as she starts to think of Home as her home. Marta, the old woman who teaches Saskia the names of all the Unthinged World’s plants and animals while taking her out to forage, instructs Saskia on the mycorrhizal relationships between mushrooms and trees—a symbiosis that benefits each species. “They’re more than friends,” she explains, intertwining her fingers. “They need each other to survive.”

That notion of interdependence is central to the questions at the heart of Fierce Little Thing: Do we, in fact, need others? What dangers lie in that need? Can one be independent and yet also a part of a community? And if that balance is reached, how might it liberate us from both codependence and loneliness? I know I couldn’t ask those questions if it weren’t for that special bit of pine woods right at the lip of a quiet, small lake, where I’ve been lucky to spend more than a few quiet afternoons dreaming up another world.

***