This year marks the twenty-sixth anniversary of Law and Order: SVU, which has aired continuously since September 20, 1999. The hour-long drama features the Special Victims Unit of the New York Police Department, who are charged with investigating sensitive, “especially heinous” crimes against vulnerable people—primarily crimes of sexual assault, abuse, exploitation, and trafficking.

Very bad crimes, done by very bad people, in near-constant syndication on a show that has also managed to host countless icons of popular culture as guest stars—Robin Williams, Chloe Sevigny, John Ritter, Serena Williams (as a hoopster!), Martin Short, Elle Fanning, Whoopi Goldberg, Henry Winkler, Zara Saldana, Jerry Lewis, and even Murder She Wrote’s Angela Lansbury, among many others. Drawn from Hollywood, professional sports, and the music industry, SVU’s guests come to the show at the top of their games, not as a way to get started. They take on roles as villains, victims, or vice because they want to. Because it means something. Feels good.

With more than five hundred episodes behind it, Law and Order: SVU might be considered the Platonic ideal of the TV procedural: each show stands alone, a one-shot narrative with a tidy resolution, while the workplace world built around our investigators becomes so emotionally rich over the span of seasons that we learn to claim every member of the ensemble cast as ours to gossip and speculate about—our eccentric found family who will never change or disappoint us. In the microcosm of the procedural, we seek, perhaps above all, a performance of comforting and absolute competence. These shows deliver the fantasy of just laws and a reordered community in which every victim is listened to, believed, and fought for, and every case is open-and-shut. As Emily Nussbaum put it in the New Yorker, “For all SVU’s excesses, we expect it to keep one promise: no matter how bad things get, the story will end.”

SVU is the same age as its relatively recent, and highly enthusiastic, Gen Z audience, who follows the only remaining original lead, actress Mariska Hargitay’s Captain Olivia Benson, as she is challenged alternately by her convictions and the limitations of the legal system. Benson joined the unit as green as they come, partnered with Christopher Melloni’s Detective Elliot Stabler, and we soon learn that Benson is a survivor herself, and therefore motivated by a righteousness that frustrates everyone for whom the work is only a job.

Guaranteed closure and earnest conviction: these are powerful appeals in the increasingly uncertain and divided world of late-stage capitalism, and SVU continues to draw millions of viewers every week—including writers Roxane Gay and Carmen Maria Machado, both of whom have spoken about their love for the show that Machado considers a modern-day “fucked up Western fairytale.” Even Taylor Swift is on record as a fan; her Scottish Fold cat, with an estimated net worth of nearly $100 million (and presumably a fan of at least purring in Swift’s lap during an SVU marathon), is named “Olivia Benson” after Hartigay’s character. For ordinary viewers, procedural mysteries like SVU and their medical procedural cousins, including the evergreen Grey’s Anatomy and House, inspire countless fanfictions and rewatch podcasts. When the procedural format embraced forensics and crime scene scientists in the early 2000s via docu-series like Forensic Files and TV’s CSI franchise, as well as the work of bestselling novelists including Patricia Cornwell (whose Scarpetta is in the process of being adapted by Prime Video) and Kathy Reichs (whose Temperance Brennan inspired Bones), we even saw ripples in the United States’ IRL justice system. Detectives and prosecutors scrambled to catch up to the ideal that no crime is committed without leaving clues while simultaneously struggling to overcome the unrealistic expectations that the scientifically documented “CSI Effect” inspired in juries.

Procedural book, television, and film series are a catechism, a soothing and cherished mantra against feelings of dysregulation and fear. The Equalizer, whose CBS reboot stars Queen Latifah and is now in its sixth season, makes this promise explicit by offering justice directly to the disenfranchised: in every incarnation of the premise, the protagonist, a retired intelligence agent, advertises their services, “Need help? Got a problem? Call the Equalizer.” The current CBS series takes this vow a step further, promising in its tagline, “Injustice will be equalized.” In most episodes, Latifah’s Robyn McCall goes head-to-head against enemies who embody current societal problems, from transgender discrimination to refugee trafficking to domestic violence. The diverse cast illustrates the triumph of progressivism in all of its muscular and unyielding power.

While The Equalizer, along with SVU, CSI, Bones, and their cozier counterparts like Murder She Wrote and the reissue of Matlock with Kathy Bates, have invited criticism for their lockstep and formulaic structure, it’s the formula that makes the viewing experience soothing. On a procedural, justice is inevitable, and the journey is the point. The viewer is along for the ride, relaxed and free to ponder the larger issues at stake or to fixate with delight on a favorite slow-burn ship. Perhaps this is why Roxane Gay has said she does most of her writing “lying on my couch and watching Law and Order”: the procedural doesn’t compete for her attention so much as it creates a comfortable backdrop for Gay’s creativity.

The appeal of the procedural is, in this sense, a shade different from the appeal of a sleuth mystery or even of true crime. Consider the jokes about there being “nothing more soothing than true crime before bed,” the popularity of “relaxing with my murder podcast” and stepping into a space of being “basically a detective.” True crime and sleuth mysteries explicitly invite the audience to participate in the work of solving a crime. They tell their stories in a variety of different ways, with only the sleuth themself (or the podcaster’s soothing narrative voice) remaining constant from one episode to the next. The procedural, by contrast, is an established step-by-step procedure of storytelling. It presents its case not so much for the viewer to solve (although we’re welcome to speculate) but rather to make a frame for what the viewer is truly interested in—whether that be complex character issues, anger, advocacy, romance, found family, friendship, or all of the above.

Of course, there’s no hard-and-fast dividing line, but it’s interesting as novelists to think about the procedural as its own separate space in mystery storytelling. Much of the advice given to budding mystery novelists is grounded in the assumption that readers will strive to solve the mystery alongside the protagonist, and many do. On the other hand, surely one of the pleasures of a long-running mystery series is that there is no requirement to stay one step ahead of our sleuth. Kay Scarpetta, Temperance Brennan, and even Stephanie Plum can be trusted to get their guy. Deep in the Kinsey Millhone alphabet, we know that the procedure by which Kinsey solves the titular mystery will involve a jog on the beach, a conversation with her landlord, and one or more episodes of mortal peril, along with half a dozen changes of clothes. Sara Paretsky, author of the V.I. Warshawski series (launched in 1982, with its most recent release in 2024, a longer-running series than even SVU) and founder of the professional author group Sisters in Crime, likewise blurs the lines between procedural and amateur sleuth, adopting a handful of beloved plot beats that she utilizes in every book to tell the reader where they are and where they’ve been in the mystery, and to remind us that the bad guy can’t stay ahead of Vic.

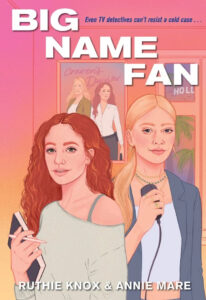

Our upcoming mystery debut, Big Name Fan, embeds a fictional TV PI procedural called Craven’s Daughter alongside its actors’ attempt, five years after their show has wrapped, to solve the murder of one of the show’s crew members. There’s nostalgic fandom here, placed in conversation with fan critique of a network’s shortsighted decision-making when it comes to queer ships, but there’s also an acknowledgment of Mariska Hartigay’s observation that the longer a show goes on, the harder it can be to tell the actor apart from the character she plays—even for the actress herself.

Maybe that’s why, as readers of these books and audiences of these shows and podcasts, we find ourselves loyal to particular series and to characters and can even be reluctant to explore a new fandom or book. Novelty is in the details, but not in the voice. Not in the familiar home that a procedural makes for its mystery, whether it be dark or light, romantic or gritty.

Olivia Benson, as ever, has got this, and she understands, especially, why you’re here.

***