I’m hardly the first author to call herself a perfectionist. In fact, I’m sure many of us were once described as “a pleasure to have in class”—which, for me, meant straight As, crippling social anxiety, and a paralyzing fear of getting in trouble. My literary role models were Nancy Drew, Matilda, and Ella (of Enchanted fame)—girls who, despite their precociousness or rebellious streak, were brave, kind, and good. Even when they broke the rules, it was always righteous, never evil. They were, to put it bluntly, likeable.

So imagine my surprise when, one auspicious day in middle school English, I was assigned And Then There Were None by Agatha Christie. In this book, the characters were selfish, cruel, and hiding terrible secrets—or, in some cases, claiming them proudly. It was a magnificent paradox for my adolescent brain: these people had done awful things, and still, I was rooting for them to make it out alive. Not only that, but I was also, in a way, rooting for the killer and their unhinged quest for justice. It was a feeling that haunted me long after I closed the book. I was hooked. While I didn’t yet have the buzzword for it, this was the beginning of my obsession with “unlikeable” characters—and the journey of self-acceptance they’ve inspired in me.

It’s no surprise that one of the next books that really sunk its teeth into me was Pretty Little Liars. I tore through this series the way you’d read a stolen diary: ravenously and completely unable to look away, even though you feel like you probably should. The Liars were badly behaved, mean, and effortlessly cool—everything I wasn’t, as a socially awkward middle schooler whose favorite t-shirt was purchased at Wicked the musical. Plus, as with And Then There Were None, there was an undeniable schadenfreude in watching the Liars get a taste of their own medicine.

Fast-forward to sophomore year of college: I picked up Sadie by Courtney Summers, discovering both a favorite author and a whole new catalog of “unlikeable” girls. Sadie, like many of Summers’s protagonists, is angry, desperate, and without options. Impoverished and abandoned in a small town, she is devastated when her younger sister, Mattie, is murdered—so, with nothing left to lose, Sadie embarks on a quest to get revenge on the man who killed her. Understandably, Sadie is not warm or kind: she is sharp-edged, reckless, and hell-bent on justice. She’s a girl who wants to be dangerous. She has more important things to worry about than likeability.

She’s a girl who wants to be dangerous. She has more important things to worry about than likeability.Still, I’m often surprised to see Sadie described as unlikeable. Her actions—though impulsive and violent—are motivated by a deep love and grief for her sister and a righteous anger at the systems that have failed them both. She is a character to root for, to ache for; you hope her quest for vengeance succeeds just as strongly as you wish someone, anyone, would give her a hug and a meal and the care she so urgently needs.

Sadie also brings to mind another “unlikeable” heroine from my adolescence: Katniss Everdeen. Like Sadie, Katniss is cold, lethal, and a survivor. Even her romance with Peeta is, at first, a PR strategy intended to soften her, thus earning her sympathy with much-needed sponsors. But, like Sadie, Katniss’s violence is motivated by her love for her sister, whom she famously volunteered for the Hunger Games to protect. She kills not because she wants to, but because she has no other choice.

In fact, I can’t help but wonder how the The Hunger Games franchise might be different had Katniss not volunteered for Prim and instead been chosen herself. Without her willing sacrifice, would readers still empathize with Katniss? Is it enough for a girl to be a victim of the world around her, or must she also be on a selfless quest—and thus excusing her own unlikeability?

The more I think about it, the murkier “unlikeability” becomes. What even makes a character unlikeable in the first place? When the word is hurled at characters ranging from the selfish, mean, and deliciously petty girls of PLL to the violent but righteous heroines of Sadie and The Hunger Games, the criteria seem endless. “Unlikeable” has become a catch-all term for girls who are too much of something—too angry, too soft, too strong, too weak. Girls who are too feminine and therefore shallow and emotional—the Liars—or maybe girls who aren’t feminine enough—Katniss and Sadie, who are rough and mean and uninterested in romance.

“Likeability” is, like most of the femme experience, a trap. This is hardly a revelation (we are living in a post-Barbie world, after all), and it doesn’t even scratch the surface of how this unfairness is magnified for characters who aren’t straight, white, cis, and in some way conventionally attractive. Still, as a young woman, it was so freeing to understand that “likeable” is unattainable, especially when it came to my own writing.

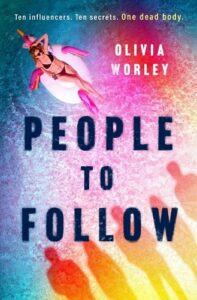

With People to Follow, my debut novel, I’ve come full-circle. Inspired in part by And Then There Were None, the YA thriller follows ten influencers who go to a remote island to film a new reality show, only to end up stranded with a dead body…and a mysterious “Sponsor” threatening to expose their darkest secrets. Of course, writing about influencers felt like the perfect excuse to create some delightfully detestable characters. Elody, for example, is an Instagram model with boundless overconfidence, no filter, and, like, a totally over-the-top LA affect, babe. Logan, on the other hand, is spiky and sarcastic; she’s a disgraced TikToker whose jokes trend dark and border on mean.

All ten influencers are guarding a juicy secret of some kind or another, and I’ll be the first to say that they’re nearly all “unlikeable”—in some cases, even irredeemable. Still, that doesn’t mean I haven’t felt the urge to humanize them or make them easier to root for. Even now, I can’t fight the urge to be liked. (Do you like me? Does this essay come off as appropriately relatable and smart but not like I’m trying to be smart? Will you buy my book?)

Still, I get a little thrill whenever a reader calls my characters unlikeable. It feels, in some ways, like exposure therapy for the recovering “pleasure to have in class” within me. Writing them, too, was therapeutic: while many of the characters in People to Follow say and do things I would never dream of doing, they were an outlet to be rude, loud, and messy, to give voice to my darkest, angriest thoughts. They do bad things and pay the price—or don’t. They are sometimes insufferable. Most importantly, they’ve helped me hone a new and freeing belief: if I can write them and love them, in all their extremes, then maybe I can trust that I’ll receive the same—even if I have to accept my “unlikeable.”

Besides, I’m pretty sure being liked is about as easy as escaping a private island when you’re stranded with a killer—so, maybe we should all just give ourselves a break (and be glad, at least, that no one’s hunting us down one by one.)

***