A new trend in fiction, film and TV seems to be emerging where women are placed at the centre of traditionally male action thrillers. Anna Kendrick’s directional debut, Woman Of The Hour, takes the serial killer trope and turns it on its head, focussing on the true story behind the ludicrous moment a murderer appears on a TV dating show. Rather than delving into the unedifying world of the psychopath, Kendrick showcases the female protagonist relying on her own intuition to save her life. The typical narrative – of women being captured and killed by men – is upended.

Black Doves springs to mind, too: Keira Knightley plays a female spy and the narrative focusses on a marital deception; a woman who has never been who she said she was. The scenes I most remember from this are when Keira Knightley is holding a gun but is silencing her assailant – her children are sleeping upstairs. In one still, she kisses her husband, who she is reporting on, but then looks at herself in the mirror.

It’s happening in fiction, too.

The Wrong Sister by Claire Douglas has dominated the fiction bestseller lists all year here in the UK, and is about a woman targeted by a seeming-assassin who should have killed her sister. But rather than delve into the murky underbelly of contract killers, Douglas instead treads the domestic and much more interesting ground of the sisters’ jealousies of their differing lives, why one would be targeted over the other, and what that says about their shared relationship and childhood.

I think it isn’t only that women are at the centre of these narratives – it’s also that, in focussing on female protagonists, the writing becomes more emotional in tone and the stakes different in interesting and surprising ways.

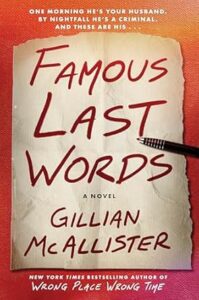

I’ve been really enjoying recently taking these typically action-based tropes and playing with them. My latest novel, Famous Last Words, takes the beats of a hostage situation but puts a female at its centre: a woman who is told her husband is caught up in a siege in central London, only to find out that he is the one who has taken three hostages and is holding a gun. He is a writer, an ordinary man, calm and optimistic and happy, and yet has committed a monstrous crime that immediately makes them – and their marriage – notorious. So why does he do it? The answer lies in a note he leaves for his wife. Part love note, but part clue.

I really wanted to explore the world of the hostage situation that has been done so often in action thrillers, but rather than snipers and stake outs, I wanted to explore love and loyalty. In the writing of it, I started thinking about what the differences are between what I’m doing and the more male action thrillers and movies that have come before me, and I think the answer is in intimacy. Female readers, in particular, don’t care as much (I don’t think) if a building is blown up, but they very much care about the smaller moments, the ones that are emblematic of larger ideas. During the siege in my novel, what spooks the hostage negotiator is that the protagonist’s husband, Luke, changes from pacing with a gun on the CCTV, to pointing the gun right at his hostages’ heads. It’s a small moment, but it’s the one readers seem to always come back to. A small piece of body language that shows intent.

The note he leaves for her was a private missive from husband to wife, but later becomes public when the media report on it. And that I think is centric to the psychological female thriller: the intimate made large.

I’ve been arguing forever that the world’s favourite thrillers are love stories (in this I’d include Castaway, The Girl On The Train, Sixth Sense…) but I think this is now more true than ever.

***