“You must change your life.”

–Rainer Maria Rilke

In prison, a therapist said I needed to find a new way to be in the world. The boy of twenty, the top gun armor crewman and decorated national guardsman and college student who wanted to build a career in the service was dead. I had to grieve for him and tell a new story, become someone new.

When I got a call to lead a workshop at Pasadena City College for formerly incarcerated students and their families, the organizer told me they wanted to focus on writing healing narratives. I had led workshops in different settings, colleges, literary organizations, PEN America’s Prison and Justice Writing Program, and the unique Southernmost Writers Workshop in the World at Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station when I worked in logistics.

Even as a student of creative writing, we readers were confronted with some sensitive material to critique. Never once had I heard it called a healing story, but from my personal experience a healing narrative is one that seeks to rebuild a person’s identity as they come to terms with a life altering event, like incarceration. To transform them from who they were to who they want to become—to grieve and tell a new story.

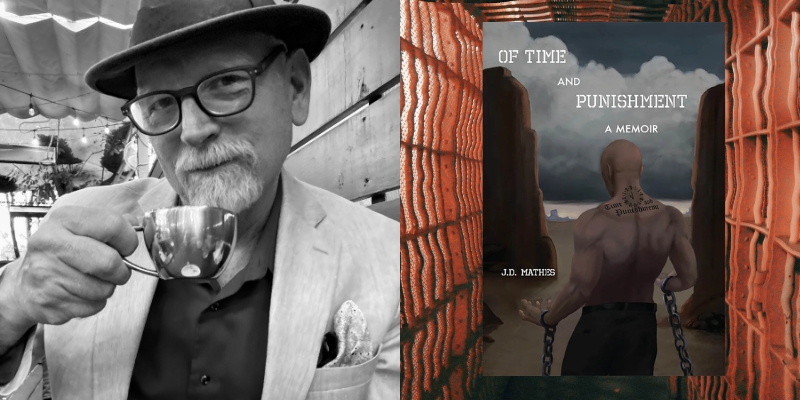

Sure, we knew about catharsis in its literary context, but this was different. I agreed, having learned techniques to share. I’d spent the last decade struggling to write about my experiences of being incarcerated, which resulted in my book Of Time and Punishment: A Memoir.

American philosopher Martha Nussbaum said, “a bad-enough experience in adulthood can wreck the noblest of character.” There is evidence that psychotherapy can change a patient’s neural pathways, but it’s a lot more complicated than smiling at the world like the Joker. What has been discovered is that telling stories can rebuild that character.

In Trauma and Recovery, the author and clinical psychiatrist Judith L. Herman wrote that Stage Two in the process of recovery from traumatic experience is the sharing of a personal narrative with those who understand and won’t judge them. Dr. Jonathan Shay confirmed through decades of work with veterans suffering from PTSD as told in his books Achilles in Vietnam and Odysseus in America.

During World War One psychologists used “the talking cure” to help heal shellshocked soldiers. My father-in-law was a trained psychologist and colonel with thirty years’ service the U.S. Air Force who worked with people suffering from PTSD. With his patients suffering nightmares, he had them tell someone the dream every morning. Over time the dreams abated, and the patients were able to sleep peacefully through the night.

In my case, for my memoir, I wrote about my arrest after aiding and abetting a friend in the theft and getting rid of a machine-gun from our armory. In that moment I lost my military career, became a felon, lost the future I thought I’d have, and turned twenty-one in prison serving two years. I had to process the guilt, my stupidity, my family’s pain, and the horror that followed in its wake. When I finally wrote it right, I felt a strange relief, but I also felt transformed. I had become someone else through the process of writing this story.

It’s exploration, really. The stories we tell ourselves have a power, as do the stories others tell about us. One thing about the people who write narratives about their incarceration is that many of them include these other perceptions of who they are. The prosecutor tells one story, the defense attorney or public defender tell a different story, family, friends, enemies, the news media, and the victims of the crimes.

It is not unusual for people to succumb to the negative stories or adopt a role from other’s expectations. By being able to take control of their narrative, they can explore who they are, informed by their life and these other stories, but now with giving themselves permission, they can write the story of who they were and who they want to become and begin this transformation. It’s about coming to terms and making sense of their life.

Even if it appears senseless, meaning can still be made of it. And isn’t making suffering meaningful the way towards rebuilding the self? Our retelling the story makes the suffering transcendent, so it imparts meaning to others. As has been said in many ways by different thinkers, no one gets out of life without suffering, but with finding meaning and purpose in suffering/trauma, you can survive and grow.

It’s not a sudden change, but story has a power to manifest itself in the world over time. It did for me and the evidence is in my memoir and the essays and stories I’ve written about my incarceration.

At the conclusion of the workshop in Pasadena, there was a celebration for the class. I met Jimmy Santiago Baca who talked about how learning how to write in prison help transform his identity from illiterate criminal to respected poet. He formed workshops in the prison to help lift others up and went on to create a writer’s retreat in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

I had become someone else through the process of writing this story.After we talked about our respective journeys, he invited me to present at his retreat. There I met many writers who after years of writing had changed themselves and lived different lives than they did when they started.

I thought of the new writers I had worked with, not just in Pasadena, but in the other universities and literary organizations I taught for and the long apprenticeship we serve to the art of writing, of the introspection we do, and how we create stories to share with others. Over time, I realized the grieving the therapist talked about was the importance of letting the old self go.

A beautiful thing is that writers don’t have to try to tell everything in one essay or story or poem or script, libretto, or book. They can keep telling stories and rewriting them in different ways from different perspectives and discover deeper meanings about themselves through their stories. Over a lifetime, they can amass a lot of stories and become better at writing them—ars longa, vita brevis—art is long, life is short.

A beautiful thing to also consider is that their writing will still be making meaning and having an impact long after they’ve run out of breath, perhaps helping future readers see how they can rebuild their own lives through writing.

***