At the cross streets of Sixth Avenue, West 10th Street, and Christopher Street in New York’s Greenwich Village sits a small oasis of a garden. Bordered by a fence on three sides, the garden is adjacent to an impressively ornate 19th century brick building that is the Jefferson Market Public Library. Few who pass by the library’s distinctive, stocky clock tower know that it was originally a courthouse, or that the fenced in garden was once the site of a massive, art-deco designed women’s prison, known as the Women’s House of Detention.

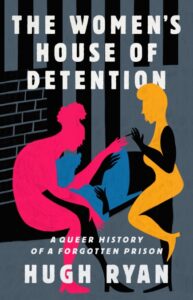

In his new book The Women’s House of Detention: A Queer History of a Forgotten Prison, Hugh Ryan recovers the complex history of the building and the women who were either incarcerated or detained there, many of whom were queer women. The House of D, as Ryan often calls it, was not far from the Stonewall bar, where, in June of 1969, queer patrons famously fought back against a police raid, sparking what many consider to be the beginning of the LGBTQ rights movement. For Ryan, the two sites—one memorialized today as a national park, the other almost completely erased—were very much intertwined. “The House of D helped make Greenwich Village queer,” Ryan writes, “and the Village, in return, helped define queerness in America.” In his deeply researched and illuminating book, Ryan tells the history of the prison not only through personal stories but also the social and political shifts during the 20th century in how queer women’s lives were contained, regulated, and criminalized through an ever complex and paradoxical criminal justice system.

I recently spoke with Ryan about his research into the House of D, it’s erasure from public memory, and the legacies it has had on our culture of incarceration.

James Polchin: What was the Women’s House of Detention and what drew you to write a book about it?

Hugh Ryan: The Women’s House of Detention was a 12-story, maximum security detention facility for women. I refer to it throughout the book as a prison but it actually functioned as both a prison and jail, which means it held people who were sentenced and people who are awaiting trial. It opened in 1931 technically, but I think the first people incarcerated there was in 1932, and it closed at the very end of 1971, though I think the last people to leave was in 1972. So it dominated Greenwich Village life for most of the 20th century.

I was drawn to it for a couple of reasons actually. When I was working on my first book, When Brooklyn was Queer, I encountered people whose lives flowed through it at some point. Or, if not the Women’s House of Detention, then the women’s court [now the Jefferson Market Public Library]. The court predated the Women’s House of Detention, but was in the same location, and is part of the reason why the House of Detention was located in Greenwich Village. I was already thinking about prisons as places where queer history gets recorded because of arrests and because of the ways that doctors and guards watch prisoners. But as I began to research the Woman’s House of Detention, I saw a much broader role that these places played in queer history.

It helped that after I had seen those connections from my first book, I went on a tour with Jay Toole, who was formerly incarcerated in the prison and is an incredible activist these days in New York. She leads tours of the West Village, telling people about the Women’s House of Detention. And then they’re all these other, suddenly small details where the House of Detention popped up. I was reading Joan Nestle and there was the House of Detention. I was reading Audre Lorde and there was the House of Detention. I was talking to the author Lisa Davis, and she said kind of idly one day. “You know the boys, their bars pop up wherever you have an elevated train. There’s a gay bar section in Times Square and there’s a gay bar section down here and there. But the girls were only in Greenwich Village and I never understood why.” And I was like, well that’s actually a question I had never thought to consider: why Greenwich Village? And so the details just kept pointing to the House of D, and I knew nothing about it. It was five-hundred feet from Stonewall, but wasn’t part of the history of the Stonewall riot. It just suddenly felt like there was this big hole that I could feel the edges of. That’s where I really love to do my research—something that feels like it should be in the public memory that feels central and yet isn’t there.

JP: The connection to Stonewall is central to the story you tell. You write about how, on the night of the uprising, the women in the House of D joined in the resistance with their own protests. Can you talk more about that prison protest, which is certainly something we haven’t included in the annual Stonewall commemorations?

HR: Some of the incarcerated folks could see the Stonewall Inn, and could see the uprising. Not all of them could hear it, but they could smell it. The writer Arcus Flynn said the first way she knew it was happening is she saw points of light flying through the sky as she was driving and she didn’t know what they were. She stopped and pulled over and she realized that it was women setting fire to their belongings at the House of Detention and throwing them out the window while chanting “gay rights! gay rights! gay rights!” The writer Rita Mae Brown, who was on the ground in the Stonewall riots at that time, remembered seeing this too. But it just gets dropped out of the conversation over and over again. I will say there was a riot in the prison that night. We don’t have any good records of it except that the New York Age, the very important black newspaper in New York, wrote an article a week later about seven women who were disciplined for attempting to escape that night.

What exactly happened is hard to know. But what we do know is that these folks in the prison had rioted previously many times, sometimes in concert with things happening on the outside, sometimes on their own. They understood that setting fires to their belongings and throwing them out the window was a way to get attention. Many people in the prison were queer themselves and had histories of resisting the cops and arrests.

There were other folks with incredible political educations who were in the prison that night. For example, Afeni Shakur [Tupac Shakur’s mother] and Joan bird, both leaders in the Black Panthers, who had been arrested on conspiracy charges in April of 1969, were held in the prison on the night of the Stonewall riots. Afeni Shakur actually talks about how seeing gay liberation banners outside the prison helped her to understand the politics and reality of queer life. The connection she made in the prison helps you bring those things together. After she got out of prison, she was pushing here girlfriend, Carol Crooks—who I was able to talk to and interview—to get more involved with the newly formed Gay Liberation Front to raise money for them. When Huey P. Newton comes to New York City he writes a letter about how the future of the Black Panther Party is connected with Women’s Lib and Gay Lib. Newton wanted to do a press conference and he held it at Jane Fonda’s apartment. Afeni Shakur called the Gay Liberation Front and had them send people to Jane Fonda’s apartment to meet with her and Newton to discuss working together. She goes to the Black Panthers Revolutionary People’s Constitutional Convention and works with the gay men’s group to help them formulate their demands. She is living at one point with Joan Bird and a couple of members of the Gay Liberation Front in an apartment in Greenwich Village. The prison for women was a place that connected a lot of political struggles and enabled women to think about their lives in different ways, away from men and away from heterosexuality.

I think this gets at why Stonewall matters. It doesn’t matter because a group of people fought back against the cops for one night at a bar. That happened before, and it was going to happen after. What matters is all of the people who were organizing and bringing that energy together, making the Village a queer political space.

JP: Right, and an important strength of your book is how you intertwine the history of this prison with Greenwich Village in those decades, and particularly the development of a queer political consciousness that was emerging around the House of D.

[C]ollectively, we can imagine ourselves beyond white supremacist, hetero patriarchy because as a group we can see the ways we are commonly oppressed by it. And I think that is what the House of D did for Greenwich Village.HR: Whenever I would read histories of the folks who were leaders in the early gay rights, homophile movements almost all of them say at some point, “Well my first experience before I joined the homophile movement was being at the bars. And at the bars I got to see queer people and to imagine us as more than just individual freaks. And I can see us as a community and see what was possible.” And I think that those kind of lumpen proletariat who never get named, who are the vanguard of this thing that we call Pride, are the very folks who were filling the House of Detention and other detention facilities too. They are working class people whose lives aren’t remembered because they did not have the power, or the ability, or the money, or the prestige to form an organization like the early gay rights organization called the Mattachine Society. Or they were so multiply oppressed by race and gender and class that they never had the time to do something like that. But that idea, what the artist and activist Tourmaline wrote about as “freedom dreaming,” a concept from black liberation thinking. It’s an idea that collectively, we can imagine ourselves beyond white supremacist, hetero patriarchy because as a group we can see the ways we are commonly oppressed by it. And I think that is what the House of D did for Greenwich Village. It concatenate women and trans men in that area for decades, thousands of them, many of them queer at a time when queer spaces had been shut down or raided. The Village is filled with these people who understood that the criminal justice system was targeting them unfairly, often without evidence, who had a political outlook, simply because it was their lives and their struggle to survive. They may not have been involved in electoral politics or consciousness raising politics, though people involved with the House of D were involved in all of those things over the course of the decades. But I do think that they are the ones largely who helped to conceptualize the idea of Pride and of living outside of heterosexuality that so much of gay liberation is built on.

JP: You dedicate this book to the “memory of the forgotten,” as you phrase it, and throughout you focus on recovering the stories of women who were incarcerated in the House of D. The book is shaped by the words and experiences of these women, many of them people of color and queer. I’m interested in the challenges you faced in finding these voices and finding material to tell these stories.

HR: That was the biggest challenge. The entire first year of doing research was just trying to figure out where I would find the right kind of information to tell the story. I didn’t want to tell a story that was entirely from the official records of the prison because I didn’t trust those records, and I think that they are intentionally dehumanizing as they treat incarcerated people as fungible numbers, not as human beings with experiences and lives and thought.

So in my initial thinking I looked through all the periodicals or newsletters or meeting minutes of early LGBTQ groups or social organizations, and really struck out. I found little moments of discussion of laws, occasionally, but primarily only in relation to arrests for specific gay crimes You can find discussions of soliciting, occasionally even masquerading, but that was kind of it. And then I thought, well I’ll look at the records of famous or well documented LGBTQ people who are kept it the New York Public Library and maybe I’ll find something in their diaries or in their letters. But even there, there was not a ton.

Then I had to really rethink. Maybe the materials I need to tell the story that I want to tell are just not out there. All the books about historical prisons, particularly prisons for women, talk about how hard it is to find information from inmates’ point of view. So I spent a long time thinking about how does one end up in public history? How do you get into the archive? And there are two ways: you either have the power to preserve your own records or you have money or you’re famous so people want to write about you. Or, other people have power over you and you’re the raw material for their entry into public history. This second way is prisons taking records on you. But it’s also police, it’s also doctors, and its parents and its social workers. That’s what I finally hit on, that folks who were social workers working with incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people were likely to have kept notes that would at least give me an outline of their lives. I didn’t expect to find the robust kind of files that I did end up finding. I thought I would find names of people who were queer and had been incarcerated and I can do all this other research around them. Of course, when I opened up the files, I found that there was so much more there. The Women’s Prison Association kept incredible notes, and whoever had the foresight to donate them to the New York Public Library in the 1980s preserved an incredible archive.

JP: The Women’s Prison Association was such a vital source for you in this book. What was the WPA and its role in the history of the House of D?

HR: The WPA was a spin-off of the Prison Association of New York, which is one of the oldest correctional related nonprofits, as we would call them today, in existence. It was in fact the first standalone women’s penal organization in America. They split off from the Prison Association in the late 1800s, and by the early 1900s they were providing services to a lot of incarcerated and formerly incarcerated women in several ways. They established Hopper Home, which still exists in Manhattan as a transitional group home for formerly incarcerated people. They also provided social work services and they worked directly with people who were leaving the House of D and the Women’s Court. They also provided the funding for the psychiatric and social work services in the prison for many years. Staff members from the WPA were often working in the prison. This ensured a really close collaboration between the two organizations, and produced rich, detailed documents. During the Great Depression, New York City didn’t even bother to put out annual reports from the Department of Corrections for the entire decade. But in that time period because the WPA was funding these services and therefore funneling formerly incarcerated people directly to their outside organization, they have a kind of note taking that almost no one else was doing. Or if they were doing it, they certainly weren’t preserving it. The files get less useful in later years as folks became less interested in funding work with formerly incarcerated people, and as the country becomes more conservative as the nature of the such social work changes. But in those early years that connection to the prison was really crucial.

JP: You show how the WPA and the prison were often intertwined in the women’s lives for many years. You write, “The House of D remained a dominate force in the lives of the many women long after their incarceration ended.” What do you mean?

HR: A lot of things. There are the formal ways. For instance, if you wanted to work in nightlife in New York City, you had to have what was called a cabaret card. Cabaret cards were given out by the police—and solely at the discretion of the police—and you had to be fingerprinted in order to get one. This comes about largely during World War I and World War II. The police set up the fingerprint drive right down in the Village because that’s where the Women’s House of D was. For formally arrested women, if you wanted to be anything from a bar waitress to a stripper, you had to come back there to get your fingerprints taken. If you were still seeing a psychiatrist funded by the WPA, you might still be taking those meetings in the prison or somewhere nearby. If you were going to visit someone who had been arrested, you were going to come back to the Women’s House of Detention—whether that was a formal visit or a street visit because they could yell up and down from the street to the windows. If you tested positive for a venereal disease, gonorrhea or syphilis, it was likely that you would be sent to a detention hospital, and in New York that largely meant the House of D, though, you could also be sent to certain parts of Bellevue or some other places.

Then there were the informal ways that it remained in their lives. One of the things that comes up from the 1930s through the 1970s is that butch lesbians hung out in the nearby drugstore called Wayland’s on Sixth Avenue, because there was a soda fountain and a payphone there, and they could watch the women coming in and out who are being arrested. Women talk about going down there in their free time to hang out outside the prison in the chance of meeting a lesbian. It was a landmark. It was a place that people came to—both those who had been incarcerated and also tourist New Yorkers who wanted to see the Bohemian side of Greenwich Village. The prison is largely what gave the neighborhood that Bohemian atmosphere. And so, in all of these ways the prison remained in these people’s lives. There’s a great Audre Lorde quote where she talks about how it was always there as a feeling of “one up for our side.” Even though it’s a prison, even as a source of punishment, it was also a place of female resistance, she says.

JP: The book is filled with fascinating details about policing sex in mid-century America, a history that seems acutely important as we think about the ongoing efforts to regulate sex and sexuality today. One moment I was really compelled by was your discussion of “The American Plan.” What was it and what is its legacy?

HR: The American Plan is shocking. It’s one of the elements of the book where I was like, is this even real? Starting in World War I, particularly 1919 which is a big moment for the American Plan, the U.S. government pressured every Attorney General around the country to work with them to find, test, and, if found to be positive, incarcerate women and girls who were thought to have gonorrhea, syphilis, or possibly some other STDs. This had nothing to do with their health. It was about girls and women as disease vectors spreading to military men. This plan, which lasted through World War I up to World War II and through the 50s, the 60s, and even into the 70s in some places, reveals a number of different things. One, it says that anyone arrested on sex work charges needed to be tested, and if they tested positive confined until they test negative. This was done at a time when the tests were terrible and there were almost no good drugs for treating these diseases. You were being treated with arsenic derivatives and mercury derivatives, both were toxic and poisonous, and oftentimes took months of treatment and didn’t necessarily cure the disease. The tests were riddled with human error, so you might get a false positive and then spend months in jail being injected with arsenic.

This is a crazy situation and reflected drastic changes in the laws around prostitution. In the early and mid part of the 19th century, there are almost no arrests for sex work. There were fines and some punishments, but neither women nor men were arrested very often. But as we get into the late 1800s and early 1900s, sex work becomes a huge issue. Thousands of women are arrested for it because women’s justice is seen as a moral issue and sex work can be a moment to fix them. We very quickly go from arresting actual sex workers to arresting anyone who might be a sex worker, which, in the eyes of the government, was any poor woman or a woman who is likely to be poor. All of these arrested “sex workers” are really just women and girls who they thought weren’t going to make a living any other way. And that included many, many queer women and trans masculine people because they were improperly feminine. They would never, so the thinking went, be wives and never be maids, so they couldn’t take care of themselves. Economically they’re going to be forced to be prostitutes, so we have to treat them as a danger to men and arrest them and incarcerate them until they’re cured. You could be found innocent of what you had been arrested for and still be held in prison for five months if they found you were positive for gonorrhea. Scott Stern wrote a book called The Trials of Nina McCall that documents the American Plan, and it is fantastic. It was really an eye opener for me.

JP: There is a fascinating thread in this book about how our current approach to drugs and addiction took shape in the early 20th century. Particularly, you show how the House of D epitomized a shift from seeing drug use and addiction as a medical concern to a moral concern, shaping a series of state and federal laws criminalizing certain kinds of drug use. Can you talk about these shifting norms around drugs use and the law?

HR: One of the things that jumped out immediately in my research is how we go from a moment where there’s not a lot of arrests for drug use in the early decades to, by the 1970s, 80% of those people who have been arrested are drug addicts, not just users but drug addicts. They may not have been arrested on drug charges. Something huge was happening. I don’t think it was just that more people were using drugs. I can see in the files who these people are and who’s using. Instead, it’s about who’s being penalized and how they’re being penalized and how drug use is being considered.

I started to look at the laws around heroin use in the late 19th and early 20th century. In New York, if you had a prescription from a doctor, you could legally get heroin. And that was shocking to me. This was one of the hardest things to wrap my own head around as I was trying to understand the move from a regulatory model, which is the model that we use for cigarettes now, where you don’t ban them and you don’t criminalize them, but you put a tax on them to punish people who want to use them. It’s a way to try and discourage use without criminalizing use. And that used to be a model for drugs and we switched over the course of the early 20th century to a criminal model. In the process, we created millions of criminals in the sense that we criminalize behavior that previously was legal.

If you’ve ever watched a show like Deadwood, it’ll give you an idea that rich white ladies used a lot of laudanum and opium in the late 19th century. That, in fact, was the image of an opium user in the late 1800s—a rich white society lady. So, in criminalizing those people, and everyone else who’s using drugs, we also created whole new classes of criminals, because now we’ve created an illegal need for what was formerly a legal product. We need whole new chains of supply to get that illegal product to folks. Previously, under a regulatory model, you don’t develop illegal supply chains because there’s always legal methods to get it. When you have a criminalized model, there is not a legal version at every step, so you have to create an entire illegal supply chain, and new criminals, and new criminal enterprises that span the country and the globe. So we created these massive groups of drug users and drug traffickers and then arrested them and sent them to jail. This transformation happens basically between the 1890s and the 1950s. We could’ve treated drugs as a legal form of entertainment or medical use. We chose not to. We go straight to a criminalization and into a moral issue. Much as we did at that same time with Prohibition and alcohol.

JP: Your book sits at the intersection of queer history, women’s history, and the history of incarceration and policing of women who didn’t conform. But this book also is about the problems of incarceration. How did researching and writing this book show you something about the history and present moment in our carceral system?

HR: One of the things I started to see right away was the abject failure of the system to do any of the things that I was told it was supposed to be doing: rehabilitation, justice, job training, keeping the people incarcerated safe. All of those things the system was an abject failure at, decade after decade after decade, through conservative administrations and liberal administrations, after there was outcry and when it was ignored, when it was funded when it was unfunded. I started to ask, what is it really doing? That is when I started to really look at and read and understand some of ideas around abolition from writers such as Angela Davis, Andrea Ritchie, Ruth Wilson Gilmore. Once I saw that the prison was obviously not doing any of the things that I thought it was doing, and that it wasn’t about justice because we would care about the recidivism rates, it began to help me make sense of what was actually happening.

We had taken a system, a 19th century—even an 18th century—conception of justice that was used to punish the anti-social, generally violent acts of mostly white men and repurposed it as a method of social control over people of color, particularly black people, and women, both of whom we’re moving into the public sphere in the post-Civil War era. As we are developing this whole new idea of incarceration, including this expanded move towards reformatories that focused on younger people, people who are more able to be reformed apparently, we were really building out an apparatus of social control over things that were not previously considered crimes like drug use and drunkenness and gender appropriateness and prostitution. And then that led me directly to seeing how important abolition is for everything else.

Before I started writing this book, I probably would have said that prisons were broken. But they’re not. They’re actually massively efficient. Everything else is broken. All of our other systems of care are absolutely broken, threadbare, letting everyone fall through them. Prisons exist as a catch basin, as a stopgap, as a pressure valve.Before I started writing this book, I probably would have said that prisons were broken. But they’re not. They’re actually massively efficient. Everything else is broken. All of our other systems of care are absolutely broken, threadbare, letting everyone fall through them. Prisons exist as a catch basin, as a stopgap, as a pressure valve. They are how we deal with every other broken system and the people who we refuse to care for through those systems. It’s where we put people who are poor. It’s where we put people who have substance abuse issues. It’s where we put people who do not have job training. It’s where we put people who have mental health issues. That can’t change until the other systems change. You can’t reform the prison because it’s like trying to take one piece of a giant pipe system and putting a new piece in but the flow is still the same. It will make the system conform to what it was before. Therefore, the only answer is a much more root approach. Abolition is the way forward, not, I think, because I wouldn’t love it if reform would work, but that reform just isn’t going to work. When you look historically it becomes so clear that reform does not work. That prisons are doing something very different than what we think they’re doing and so when we try to reform them, it just doesn’t take. It doesn’t do anything.

And so, when I read all of this and saw all of this and saw all this abolitionist thinking it really began to hammer home to me. This is what prisons do. They take care of all the people we as a society refuse to care for in any other way. The people we refuse to give healthcare to or education or housing or treatment. We live in a country that imagines care as primarily being the work of the nuclear family. Queerness is not a vertical identity. Your parents and your children are unlikely to share that sexual orientation, or that gender identity. Therefore, queer people are always in danger of losing the nuclear family protection. In a country that imagines that care comes primarily from the family and not the state, queer people will therefore always be in danger of being uncared for. Elders without descendants, children kicked out of their families, people with AIDS, folks who need gender transition services. Care is actually an operative principle around which we can build a really robust queer politics.

***

James Polchin is an Edgar Award nominated writer, cultural historian, and author of Indecent Advances: A Hidden History of True Crime and Prejudice Before Stonewall (Counterpoint).

Hugh Ryan is an award winning writer, historian, and curator living in New York. His second book, The Women’s House of Detention: A Queer History of a Forgotten Prison is out now from Bold Type Books.