I love to laugh.

I love reading stories and watching films that make me laugh.

I’m not so fond of people trying to make me laugh. You have to be really talented to try to make me laugh and succeed at it. Comedians like Dave Chappelle, Richard Pryor, George Carlin, Steven Wright, Lenny Bruce—they are the exceptions—they try and succeed at making me laugh. But I say to the rest, “Stop trying so hard. If you’re funny, you’re funny.”

I learned long ago that true humor comes from observing people behaving as people. Don’t try to be funny, just be human.

Now, I certainly know that the topic of humor in serial killer novels must be approached with sensitivity and caution, and I believe that all the writers on my list do so. While the use of humor can be a powerful tool in any kind of literature to lighten the mood or provide comic relief, it can also be offensive or inappropriate when dealing with dark and disturbing subject matter such as serial killers.

If you’re going to write about serial killers, be serious about your writing, but with an eye for humans being human. That kind of humor, when handled correctly, serves to relieve the pressure of reading about murderers and their dark deeds.

Joyce Carol Oates’s short story “Where Are You Going, Where Have you Been?” and her novel Zombie are good examples.

“Where Are You Going, Where Have you Been?” tells the story of Connie, a teenaged girl who encounters a menacing stranger, oddly named Arnold Friend, while her parents are away. Arnold Friend knocks on Connie’s door and oozing false and cheesy pick-up lines, requests that Connie let him in. The story reads like a chilling fairytale, the kind that ends in the happily ever after of kidnapping, rape, and murder, but there are elements of humor that had me as a college freshman suppressing a smile as these words were playing in my head: Connie, don’t open the door to this weirdo with the fake wig, the strange, affected way of speaking. The scene with creepy Arnold Friend speaking to her through the door was frightening and amusing at the same time. Mission accomplished. Tension relieved.

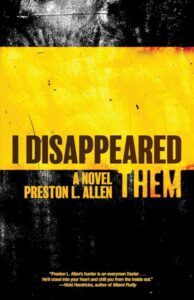

In Oates’s novel Zombie, protagonist Quentin P. comes off as charming and intelligent, but underneath he is a serial killer, loosely based on real-life serial murderer Jeffrey Dahmer. I read this powerful book after I had finished writing my serial killer novel, I Disappeared Them, which one Goodreads reviewer calls “A dark twisted tale that’s also hilarious and touching at the same time.” The online magazine Grimoireofhorror.com calls it “A riveting exploration of human complexity, blending elements of mystery, psychological depth and societal commentary into a compelling narrative.”

Hilarious and also touching? The same can be said about Joyce Carol Oates’s novel. Zombie is dark, twisted, and gruesome, but Quentin P.’s narrative humanizes him with its humor, its witty observations. I found myself suppressing smiles.

Tension relieved. Mission accomplished.

I was introduced to the works of Bret Easton Ellis as a college senior. A friend got me hip to him. I can say “got me hip to him,” because we are the same age and I assume that we were going through the same life events at the same—but Bret Easton Ellis was already published and I was still in college! Rules of Attraction was the first of his novels I devoured, then Less than Zero. The main characters were people my age. Like me, they were college students, yuppies in the making. They were serious books, but they had me laughing. Then in 1987 came his monster hit, American Psycho.

Patrick Bateman is wealthy, charismatic, and narcissistic, the ideal characteristics for a successful investment banker who is secretly a brutal serial killer. There is an extreme disconnect between Bateman’s outward appearance of wealth and success and an inner voice that is violently insane, but the combination serves to roast the 1980’s in a litany of observations and commentary on designer clothing, gourmet meals at the best restaurants, and how having a superior quality business card improves one’s status. Patrick Bateman is no comedian, but the juxtaposition of his vile acts with commentary on the merits of the new Phil Collins album is absurd and surreal. The book is dark, sure, but there are moments while reading when you can’t help but shake your head and smile. Tension relieved.

Mission accomplished.

The subject matter of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo by Swedish writer Stieg Larrson, is undeniably serious and often disturbing, but Larrson manages to inject moments of levity that serve to break up the tension and provide some relief for the reader. The novel is a dark and suspenseful tale that delves into themes of murder, corruption, sexual abuse, and rape. Lisbeth Salander, a computer hacker and Mikael Blomkvist, a magazine publisher, team up to search for the decades-missing Harriet Vanger, whose uncle believes that she is still alive because each year since her disappearance he has received on his birthday an exotic flower from her, or from someone who knows that collecting rare flowers was a passion they shared.

One aspect of the book’s humor stems from the relationships between characters. The dynamic between Blomkvist and his partner and married best friend Erika Berger, and the rest of the staff at the magazine is light-hearted and playful. Lisbeth Salander and Blomkvist are quite a pair, she the fiercely independent social outlier with her body piercings and her dragon tattoo, he the magazine editor forced to resign as a result of being sued by the crooked businessman he was investigating.

Among my favorite scenes in the film version of the novel is when Salander finds Blomkvist in the serial killer’s basement torture chamber where he’s strapped into an apparatus used in S&M sex play, struggling to breathe through the cellophane wrap covering his face. Salander gets the jump on the serial killer by attacking his head with a golf club, whacking him until he’s on his knees, barely conscious. As she is ripping the plastic wrap off Blomkvist’s face so that he can breathe, the injured, half-dead killer Martin Vanger crawls up the stairs, making his escape from the basement dungeon. Salander sees him escaping and turns her face toward Blomkvist. In a gleefully-expectant, childlike voice she requests permission to pursue the killer. She says the two words politely, like a server asking if you’d like more cream in your coffee.

“May I?”

She is gripping a golf club with which she’s beaten a man half to death and is requesting to go finish the job.

Blomkvist with the proper urgency says, “Yes.” Then she proceeds to go finish the job.

I chuckle as I type this because … tension relieved, mission accomplished. By the way, this two-word request is only in the film version. In the novel, which in my opinion is better than the Oscar-winning David Fincher film, when Salander notices Vanger attempting to escape, she says the more mundane:

“I’m going to take him.”

I’m going to take him may not be as much comic relief as what is said in David Fincher’s film. But in the novel just before Salander attacks Martin Vanger, she says, in a cold voice that cut across the room, “… I’ve got a monopoly on that one.”

The stoic Salander, who rarely spoke more than a few words, had laid claim to Blomkvist. He was her man, and Vanger who had said, “I’ve never had a boy in here before” as he tenderly touched Blomkvist’s face was treading on her sexual territory. At some point earlier, she the acerbic, tattooed outlier and Blomkvist, the ruined newspaper publisher, had become lovers. And that line I’ve got a monopoly on that one reminds that the waiflike Salander is as insane and dangerous in her own way as the sadistic rapist and killer Martin Vanger. In other words, the murderer has met his match. I smile just remembering.

Tension relieved. Mission accomplished.

Finally, there are more examples out there, of course, like the novels of Thomas Harris:

Silence of the Lambs: Hannibal Lecter’s mocking Clarice’s discomfort because of her failed attempt at disguising her West Virginia accent and cheap pocket book and Jame Gumb reciting his unnerving mantra, “it rubs the lotion on its skin. It does this whenever it’s told. It rubs the lotion on its skin, or it gets the hose again.”

Red Dragon: The unethical reporter Freddy Lounds strapped to his seat in the burning wheelchair; the facial features of Serial killer Francis Dolarhyde’s grandmother that resemble George Washington; Dolarhyde in the museum eating William Blake’s painting.

In Cold Blood: Murderers Richard Hickock and Perry Smith collecting pop bottles on the side of the road with an old man and his grandson to cash in for nickels at the gas station instead of stealing the old man’s car or perhaps killing him and his grandson as they had done to the Cutter family just a few hours before.

Finally, humor plays a significant role in serial killer novels and film by providing a means to explore complex and dark themes in a more accessible and engaging manner. Through the use of dark humor, authors can add depth to their characters, create irony and contrast, and make their stories more compelling and memorable. So the next time you pick up a serial killer novel, don’t be surprised to find yourself suppressing a smile, chuckling at the darkest subjects, or saying to yourself:

Tension relieved, mission accomplished.

***