Death is a funny thing, in that it may be one of the only aspects of life that really isn’t funny at all. You’ve got the grief to contend with, and the loss, and usually some suffering in there at some point. It’s something we all have waiting for us, a terrifying unknown that few are comfortable thinking about or discussing. So when I sat down to write a book entirely revolving around death, I knew it needed to be a comedy.

Confused? Me too, but maybe we can unpack this morbid suitcase together.

Dark topics have always been made more palatable through the lens of comedy. The term ‘gallows humour’ has been around for over two centuries, though the notion of making light of heavy subjects has likely existed as long as the heavy subjects themselves. Death is scary, and fear is powerful, but laughter can weaken that power just a little; can make the topic easier to discuss, even slightly. We see this all the time in true crime media, podcasts like My Favorite Murder popularizing the genre with professional comedians at the helm. We see it in dark comedies like What We Do in the Shadows, where mortality is a frequent punchline. So when I set about writing a novel on death, I knew there was only one tone that felt right for me. Though it hadn’t always been that way.

I first met death the day after my eighth birthday, when my grandfather passed away. It was confusing at first, and then frightening for a while, and then that fear lingered until I found myself afraid of anything death-adjacent. Taxidermy? Horrifying. The idea of ghosts? Nightmare fuel. Cemeteries? I would avoid them at any cost (something I definitely outgrew as a goth teen, but that’s a whole other story). Death wasn’t funny; it was too busy being a phobia for that.

As I grew up, I did what all good Millennials do and began to adopt humour as a coping mechanism. It helped make the less pleasant aspects of life more tolerable, brought some light to the darker times. Which certainly came in handy when, as I reached young adulthood, my mom became a Death Doula (think, emotional midwife for the dying and their loved ones) and suddenly my old nemesis was back in my life in an ever-present way. My mom had, in a sense, become a grim reaper, and I had the choice to either avoid this development or embrace the absurdity of it. Thankfully, by that point in my life, absurdity had become something of a pastime for me.

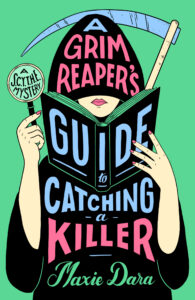

Almost as much as writing had. I’d already completed two manuscripts by the time I began A Grim Reaper’s Guide to Catching a Killer, as well as having a proverbial graveyard of incomplete works on my laptop. As a longtime mystery lover, I knew I wanted to try a twist on the genre, and the idea of a representation of death having to solve a murder was one I’d had stuck in my head for years. By the time I’d landed on a corporate grim reaper as my protagonist, the pandemic was in full swing and I, along with the rest of the world, was stuck at home twiddling my thumbs. This gave me a lot of time to think, which is often a dangerous thing for me. That thinking revolved around the kind of book I wanted to create. My two previous completed manuscripts were both comedic in nature, one a fantasy and one a middle grade mystery. After an ill fated attempt at literary fiction (I feel like every writer has to go through the ‘I’m a serious artist’ phase at some point) I realized a humorous tone was my happy place. And when I finally settled on the world of S.C.Y.T.H.E., where death is a running theme, I knew the only way I’d feel safe fully exploring the various aspects of the topic would be if I could poke fun at them, at least sometimes.

Thus began a delicate balancing act. Conner, the resident dead guy of A Grim Reaper’s Guide, died young. When Kathy, the collections agent, or reaper, assigned to his case tracks him down, he’s just a frightened seventeen-year-old kid. I didn’t want to lose his fear, or his grief at the loss of his own life. I knew those feelings were worth exploring, as much for Conner as for anyone reading who may have experienced similar emotions. I also knew that, no matter how much I love a comedic tone, it’s not easy (or particularly productive) to make light of a kid’s death. There’s an art to gallows humor, and I definitely don’t claim to be an artist, but as I got to know the characters and their dynamic more, I discovered that humour is often found in the in-between. There are moments where feelings need to breathe, and others that allow for absurdity or a joke at the expense of concepts too big and terrifying to be offended. I think that’s what surprised me most about this process; that having humour throughout gave me the emotional support tone I needed to feel safe enough to stray from it entirely at times. That I was able to explore topics I otherwise avoid talking about in my daily life, much less sink into in my writing, thanks to the comedic padding I knew I could fall back on. And that, to me, is the beauty of humour. That it can file away even the sharpest edges and render any topic graspable. And in that way, we have the opportunity to work through and even come face-to-face with our fears with a smile on.

The funny thing about death is it’s a part of life no one really likes to talk about. But maybe, if we can find a way to laugh at it instead, it can become a little less scary, or at least a little more entertaining.

***