Living in Harlem in the early 1970s, my father’s third floor apartment on 123rd and Seventh Avenue was upstairs from infamous barbershop and bar The Shalimar. Glancing out of the window on a Friday or Saturday nights, it wasn’t uncommon to see rows of brightly hued Cadillac’s lined-up from corner to corner and equally flashy men with their dolls hanging in front of their rides before parading inside the lounge. As I wrote decades later in the essay “Cashmere Thoughts” published in the 2007 book Beats Rhymes & Life: What We Love and Hate About Hip-Hop: “Every kid on the block wanted to be down with the loud suits, feathered hats and candy colored platform shoes that defined that funky-flared soul generation. The last ambassadors of black elegance, those brothers were slicker than a can of oil.”

In the beginning I had no idea who these dudes were, but after seeing the Blaxploitation classic The Mack (1973) when I was ten, I realized that the rainbow coalition of sharp dressed men were pimps. A cold-blooded flick, The Mack provided a window into a world of vice that regular folks (i.e. squares) knew nothing about; while many men were often “tricks” who had no problem paying a few bucks to spend time with a pretty woman, few had been Macks. Starring Max Julian as the title character, Richard Pryor as his bugged-out sidekick and Dick Anthony Williams playing the notorious Pretty Tony, the flick would go on to inspire folks from Snoop Doggy Dog to Quentin Tarantino, who included name checked the movie in his True Romance (1993) script.

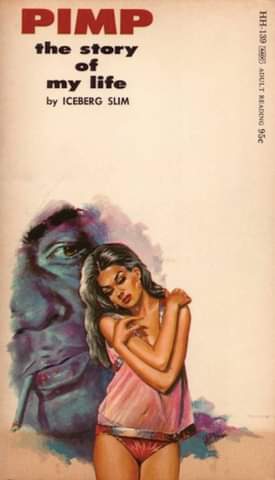

Still, in my childhood innocence, a few years passed before I realized that The Mack, as well as other pimp films The Candy Tangerine Man and Willie Dynamite, all of which I saw opening weekend at the Harlem grindhouse known as The Tapia, were themselves inspired by Iceberg Slim’s bestselling memoir Pimp: The Story of My Life. Originally released in 1967 from Los Angeles based Holloway House, the cheapo Los Angeles publishing house that later gave the world numerous exploitation novels as well as Players magazine, the book’s author, whose real name was Robert Beck, was a former “gentleman of leisure.”

A devilish man from Chicago, Iceberg Slim had turned the streets into his big pimpin’ playground for decades before relocating to the City of Angels to restart his life and spend time with his mother in her dying days. Having quit the pimpin’ profession, he worked as an exterminator by day. After-hours he and his wife Betty worked on Pimp (he dictated as she typed) and sold the raw book to Holloway House for the small fee of $1,500.

In a 1996 Observer article Iceberg Slim: Needles and Pimps, writer Sean O’Hagan noted: “Bentley Morrison, Beck’s publisher at Holloway House, remembers ‘a soft-spoken, well-built and immaculately dressed man who walked cold into the office one morning in 1967 with seven or eight typed pages of a manuscript.’ Morrison was ‘startled by the richness of the language and the overwhelming power of the story he had to tell’ and, in retrospect, credits Beck with creating a fictional genre. ‘It was black ultra realism — totally street cool and unflinchingly confessional. It allowed the reader a glimpse into a lifestyle that was alien to most blacks, never mind most whites.’”

Pimp would go on to sell millions, though it wasn’t sold in bookstores, but in urban candy stores, gas stations, record shops and head shops throughout Black America. It would also launch the genre known as street lit that included fellow Holloway House author Donald Goines as well as Sister Souljah (The Coldest Winter Ever), Shannon Holmes (B-More Careful) and Teri Woods (True to the Game). In 57-years, Pimp has never gone out of print, and has served as an influence on varied creative artists including The Hughes Brothers, Ice-T and Irvine Welsh.

In 2009 the Trainspotting author wrote in The Guardian, “Iceberg Slim did for the pimp what Jean Genet did for the homosexual and thief and William Burroughs did for the junky: he articulated the thoughts and feelings of someone who had been there. The big difference is that they were white. Unlike them, and despite one Harvard study of Pimp as a ‘transgressive novel,’ Slim was, and still is, marginalized as a writer.”

In his lifetime Slim wrote quite a few books for Holloway House including Trick Baby: The Biography of a Con Man (1967) and Mama Black Widow: A Story of the South’s Black Underworld (1969), but he never made much loot from his gritty literary efforts. Looking for other revenue opportunities, in 1976 he teamed-up with his saxophone playing buddy Red Holloway, whose band performed nightly at the Parisian Room. Red helped him get a record deal with Ala Enterprises, a subsidiary of the African-American comedy album folks Laff Records. The label’s roster included Redd Foxx, Richard Pryor and LaWanda Page, who played Aunt Ester on Sanford and Son.

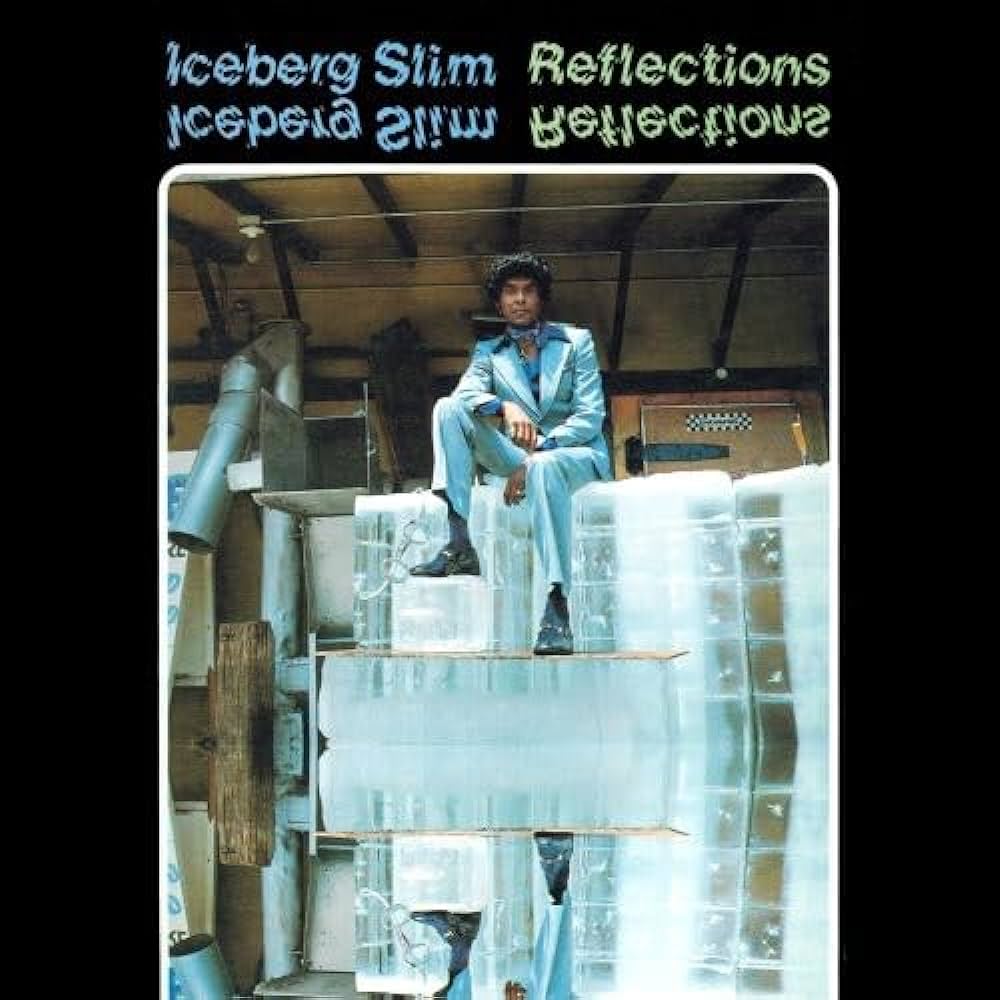

According to Iceberg Slim biographer Justin Gifford, author of Street Poison (2015), “Jazz legend Red Holloway often emceed at the Parisian and he wowed listeners by wading into the crowd playing his electric sax; he opened and closed the joint, and throughout the night he held court, announcing the arrival of pimps and black “royalty” to the crowd…It was a bravado atmosphere reminiscent of 1940s Bronzeville or Paradise Valley, and Beck (Slim) fit right in. He ultimately became a fixture at the Parisian…After hours, they often reminisced about Chicago, where they had both lived in the 1950s, and one day, Beck told him that he wanted to do a recording of pimp toasts. Holloway introduced him to Lou Drozin, the owner of Laff Records…In 1976, Beck recorded four toasts with the Red Holloway Quartet playing jazz improvisations in the background. Reflections went on to influence rappers, including Ice-T, and it predated hip-hop originals such as “Rapper’s Delight” and “The Message” by a few years.”

In 1998 rapper/actor Ice-T wrote an introduction to Slim’s last novel Doom Fox: “Iceberg Slim always kept it real. It is blatant, uncompromising and as close to the truth as you can get without going there yourself…He knew pimping. He knew hustling. He knew the streets…Black ultra-realism: totally street cool and unflinchingly confessional with a brutal twist of dark humor that you have to scratch well beneath the surface for.

“Understand, it allowed the reader a glimpse into a lifestyle and a language that was alien to most blacks, never mind most whites. In that very same way I chose to take my life experiences and put them to music. I spoke from the inside about the hustler lifestyle. I rapped about guns, drugs, gangs, and fast women. I even took on the name Ice. The most important thing Iceberg Slim did was not only show the world the game, but show young men like myself that no matter where you come from, you can always go on to that next level. My job was to show the hustlers from my generation that they too can take it to the next level.”

Reflections was a strange, but enticing album that featured Iceberg’s spoken-word reciting what is known as hustler toasts, a type of ghetto poetry that was popularized on street corners dark bars and prison yards, three places Slim knew a lot about from his hardcore life. The hard to find The Life: The Lore and Folk Poetry of the Black Hustler by Dennis Wepman (1976) is the perfect book for those wanting to know more about those streetwise poetics. In fact, Iceberg remixed the lyrics from the toast “Duriella Du Fontaine” for his track “Durealla.”

As Slim’s velvety voice dropped lyrical jewels about wicked whores (“The Fall”), his own dying mother (“Mama Debt”) or a sharp dressed pimp who becomes a shabby heroin addict (“Broadway Sam”), Holloway’s quartet supplied the laidback grooves of easy listening soulful jazz that blends perfectly with the rhythm of Iceberg’s speech patterns. On “Broadway Sam” we hear a hint of the Drifter’s 1963 hit “On Broadway” played on guitar while on the “The Fall” we get a taste of Holloway’s smoky sax, but the musical solos on Reflections only last a few beats before Iceberg slides in and starts talking about sin again.

While the album cover featured a cool picture of Slim sitting on blocks of ice, an idea photographer Robert Wotherspoon swiped from a 1968 Esquire magazine cover shot by Carl Fisher used to illustrate a James Baldwin essay, the back cover had liner notes written by the record label’s bookkeeper Shelby Meadows Ashford: “Throughout the Album you will laugh with the ‘BERG’ as he turns many a colorful phrase sprinkled liberally with licentious humor, in setting his memories to rhyme. You will also share the anguish as he rhymes poignant memories delicately laced with the despair of the forgotten…ICEBERG SLIM has been and continues to be a tremendous asset to our literary culture.”

Forty-eight years after its release, Reflections sounds a little dated, but that doesn’t make it any less interesting. A natural born shit talker, Slim’s voice is hypnotic, but he doesn’t rush through his words as he patiently schools us lames about the brutal pimping game that he never tries to glamorize. “You know the price when you’re dealing vice,” Iceberg says coldly on the opening track. However if don’t, you soon going to learn.