A tower stands alone.

J. G. Ballard’s modern fable High-Rise is almost fifty years old. In the past few decades, its potency has come closer to resembling prophecy, yet Ballard’s obsession with affluence and self-isolating communities isn’t limited to this novel alone. Novels like Super-Cannes, Concrete Island, and Cocaine Nights all invoke similar themes of alienation, isolation, and unrestrained affluence from the depths of his back catalogue, the rich coiling tightly around one another to block out the pressing realities of the wider, poorer world. Yet High-Rise remains a singular invocation, summoning a sturdy mental image with ease, a fraught zoo, a series of stacked cages, a social order imprinted on the quivering skyline in concrete—a book that has shaped its legacy at times with just a title and a stark image on the cover.

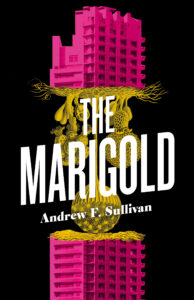

You can’t write a novel about a tower without a nod toward High-Rise. My own experiment in exploring the boundaries of vertical living, The Marigold, literalizes much of the ongoing dread suffused through each floor of Ballard’s building. The Marigold is the story of a city consuming itself, a toxic, sentient mold spreading through the condo towers of Toronto, taunting its residents with their deepest fears, drawing out their loneliness and insecurities, letting them stew in condo units already starting to show the wear-and-tear inherent to our day-to-day existence, the parts of life that do not appear in the brochure or the animated walk-through on the real estate agent’s website. A dead bird’s dusty wings imprinted on that bedroom glass forever.

So, what does draw us toward Ballard’s tower on the horizon? The nature of prophecy. Foretelling and prognostication is bound up in the very first lines of the novel, an iconic opening littering PowerPoint presentations across the anglosphere, a single sentence reminding the reader almost all of this has already happened:

“Later, as he sat on his balcony eating the dog, Dr. Robert Laing reflected on the unusual events that had taken place within this huge apartment building during the previous three months.”

We begin at an end with a warning for the narrative we will experience and what might follow. Ballard at one point considered presenting High-Rise as a social worker’s report on his unnamed 40-story building, and the narrative very much holds to that format. Splintered between three distinct points of view in the various strata of the tower, Ballard primarily references characters by their employment. Dr. Robert Laing introduces us to the tower, while the earthy documentary filmmaker Richard Wilder brings us along on his quest to reach its disputed peak, even as the injured architect Anthony Royal attempts to retain control over his new home from a deluxe penthouse suite. We meet masseuses and pilots, actresses and newscasters, doctors and dentists, all working through their own psychic breaks as the tower descends into chaos.

Ballard’s prose is unmoved by these escalations, depicting rough shoulders in the elevator and flat-out murders in the swimming pool with the same dry delivery. The details of the residents’ lives are explored through their purchases, what they own and how they abuse those possessions and those around them. Ballard’s critics often accuse his prose of a chilly affect toward his characters, a distance between their depiction and their interiority that he refuses to bridge beyond brief, singular asides. What Ballard instead uses is the accumulation of incident to explore their desires, what they actually do, and how they do it. As he puts it, “Their real opponent was not the hierarchy of residents in the heights far above them, but the image of the building in their own minds, the multiplying layers of concrete that anchored them to the floor.”

His tower does its best to reveal a true self, one that still struggles to strip away the titles and occupations tethering each person to the outside world. The accumulation of detail is much like the accumulation of ownership—it creates power, the power to overthrow communities or environments, and replace them with something new. High-Rise endures in our consciousness as this cycle does. The building’s residents are more than happy to undertake these desperate power struggles, convinced they can remake their community, isolated from the rest of the world.

Yet in our modern towers, even that sense of community can be broken. In my world, and in the world of The Marigold, the idea of a community has dissolved even further, the advances in technology since 1975 making it even easier to withdraw from the world around you. While Ballard’s characters eventually end up secluded in their own homes toward the story’s end, our modern tower residents are often even further removed from one another, a series of renters and short-term stays attempting to play at “luxury”, which was always just a patina for some middle-class aspirations toward “success” defined primarily by what has not yet been achieved. Ownership is elusive, human interaction is strained, and the food is delivered directly to your doors. As long as the elevators work and the stairwells aren’t full of dog shit, Ballard can be held off. Until a voice starts speaking to you from the drains, asking for some solace. The fantastical eventually becomes the mundane, even in The Marigold.

Ballard could see this. Surveillance is integral to the structure of High-Rise, the camera a participant in the dehumanization of his characters. Decades before everyone held a living camera in the palm of their hand, Ballard gave one to his documentarian Wilder as he explored the tower, recording incidents of violence, collecting the fragments for posterity, the building becoming an archive of its own degradation. As Ballard declares,

“The true light of the high-rise was the metallic flash of the polaroid camera, that intermittent radiation which recorded a moment of hoped-for violence for some later voyeuristic pleasure. What depraved species of electric flora would spring to life from the garbage-strewn carpets of the corridors in response to this new source of light?”

The world of The Marigold is what sprouts here so many years later, invoking this surveillance on monitored streets, riding temperamental elevators, or in the bedrooms of the lonely and the damned. In the years since High-Rise’s publication, the desire to claim our attention has only accelerated, the speed and breadth of our knowledge often exceeding our capacity to do anything about what we see and experience. The residents in our modern tower begin to make money from coopting this surveillance, streaming their lives to the outside world, selling their own time to continue living in the sky. This was part of Wilder’s dream before he was diverted from the task at hand by baser instincts—food and water and lust overtaking any desire to create. What this perpetually increasing modern surveillance reveals is the same song Ballard sings throughout this novel, “the old social subdivisions, based on power, capital and self-interest, had reasserted themselves here as anywhere else.”

Ballard’s tower in High-Rise is only 40 stories, barely worth acknowledging in a modern metropolis. We have doubled this while somehow housing even fewer people. These towers require sustenance to live. Bodies to fill them, bodies to pay for them. Bodies are the first and final currency for any work. The novel ends with new buildings sprouting up around that first tower, a parallel spire greeting Robert Laing from across the acres of parking lot, one of its floors already blinking out of existence in the night, the power unstable in this fresh, uncanny structure:

“Already torch-beams were moving about in the darkness, as the residents made their first confused attempts to discover where they were. Laing watched them contentedly, ready to welcome them to their new world.”

A tower stands alone. Until it doesn’t. Until the entire horizon is filled with glass and concrete, every room isolated with its own perfectly obstructed view, an accumulation of our collective alienation. A new Marigold growing across the street, for no reason beyond greed or boredom. Ballard saw this as a vision of the future, one where most of the ownership was still located in the building itself. But the suites these days are often just investments in a city like Toronto, holders of value, vessels for hidden wealth, the engine for even more mindless accumulation. Housing as an asset rather than a right, the hoarding happening in public before our eyes, the numbered corporations of the world rejoicing in the bloody run-off of a fiscally rewarding crisis.

Slimmer towers fill in the choked sky, while the actual population itself remains unfulfilled below, that missing middle the urban planners of the world shriek for swallowed up by ravenous greed, architectural arrogance, ongoing capitalist surveillance, and the ancient truth of pure, unbridled spectacle. The world of High-Rise has accelerated, exceeding its own image, manifesting so thoroughly the fiction wears thin and reality begins to flicker at its edge. Or as Ballard himself might put it, “this hanging palace self-seeding its intrigues and destruction.”

Eventually a tower falls, part of the same prophecy. And that too is a spectacle all on its own.

***