On January 27, 1943, the first American women’s expeditionary force in history landed in North Africa. This company, the 149th Post Headquarters Company, had been specifically requested by General Dwight D. Eisenhower to work at his Allied Force Headquarters (AFHQ) in Algiers.

At the time, the Women’s Army Auxiliary Force (WAAC), was a controversial corps of women attached to the United States Army. Women in uniform were an anomaly in American life and their assignment to a combat theater was unprecedented.

Initially, General Eisenhower himself opposed the use of women in uniform, but after serving in London, he had seen firsthand how British women filled out the ranks and helped the war effort by serving in non-combat military roles. The 149th Post Headquarters Company was an all-volunteer group of highly qualified women sent over by Oveta Culp Hobby, commander of the WAAC.

The company was led by five female officers who commanded this newly formed auxiliary force. As auxiliaries, they were outside traditional army command, working in conjunction with regular army. These forgotten heroes played an integral part in helping to win the war.

The roughly one hundred fifty women soldiers worked as typists, translators, codebreakers, switchboard operators and more. They even worked in a top-secret headquarters planning the invasion of Sicily. General Eisenhower himself assigned six WAACs to his office and engaged several WAAC drivers to man his staff cars.

The main switchboard at AFHQ, called Freedom, was in dire need of help and almost half the WAACs in the 149th were assigned to man the telephones, putting through vital calls as the Allies battled the Germans in Tunisia. The male callers were surprised to find an American woman on the other end and often begged them to speak, not having heard the voice of an American woman in some time.

The WAACs worked in almost all major sections of Allied Force Headquarters and were an integral part of the successful North African campaign.

When they first arrived, there was much skepticism and criticism of the WAACs. Enlisted men and officers alike expressed unease at women’s presence in a combat theater. Some were outright hostile. Some warned their girlfriends back home not to join the WAACs. Many men told the women they belonged at home.

But throughout the campaign, the WAACs proved themselves to be capable soldiers and as the war progressed, the demand for women soldiers only grew. Before long, officers and generals were vying for WAACs to work in their offices.

In fact, it didn’t take long for the men at AFHQ to realize that having women in a combat theater might be beneficial in unexpected ways. Almost as soon as the 149th Post HQ CO arrived in Algiers, various Army and Navy companies arranged dances and social engagements to draw the WAACs out. And the Americans weren’t the only ones. British companies did the same. Soon, battle weary soldiers coming to the city for some rest and relaxation found themselves dancing with American women and enjoying some sense of normalcy in the midst of a theater of war. Most of the WAACs were happy to blow off some steam after work and dance with GIs, although some chafed at the presumption that they were there to entertain the troops. They’d signed up to serve their country. But generally, the men and women fighting for freedom were happy to have each other in a strange land, so far away from home.

Though fraternization was technically verboten, more than one officer dated an enlisted WAAC. Since the WAACs were an auxiliary force, the army had no disciplinary jurisdiction over the company in Algiers. The women were not disciplined the same way as regular army soldiers, so any mild indiscretions were often overlooked.

But life in a combat theater was not easy, even for those working behind the lines. When they’d volunteered for overseas duty, the women knew they risked being killed, but because they were an auxiliary force, they did not have the same protections as their male counterparts. Their families did not receive life insurance if they were killed in a combat theater. They were not included in any of the usual protections afforded to men if they were captured by the enemy. Initially, the women even paid for their own postage on letters sent home, a service the men received for free.

The company was billeted in a sprawling 18th century convent. They lived in large dormitory-style rooms, slept in rickety, hastily built beds without the luxury of pillows. They washed up in the central courtyard, drawing water from an old well and using their helmets as sinks. Soap was scarce and hot showers were unheard of.

Just the day after their arrival in Algiers, the Luftwaffe bombed the city. Over the course of the next few months, the WAACs endured over sixty air raids. One night their convent was hit. The women huddled under their blankets while some of their fellow auxiliaries patrolled the rooms and halls “armed” with first aid kits in case anyone was injured. Women were not allowed to carry firearms. During one raid, some unexploded shells went through the convent roof, just missing the bed of one of the WAACs, showering her with plaster. Luckily, she escaped with just a few scratches and bruises. After the war, one WAAC described hiding in her closet during thunderstorms for the rest of her life.

Despite the dangers and inconveniences, and the long hours at work, the WAACs managed to have some fun. They joined a play put on by the Signal Corps and entertained the troops coming to Algiers for some R&R (rest and relaxation). They attended dances and dinners, and even attended a tea party at the Governor’s Palace at the express invitation of the French General, Henri Giraud, head of all French forces in North Africa. They worked and socialized with their British allies. They swam in the Mediterranean and explored nearby historical sites. But in all their descriptions of their service at AFHQ, their fondest memories are of their service to their country.

It would be several months before the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps transitioned to a fully integrated army corps, renamed the Women’s Army Corps. During their time as auxiliaries, the 149th Post Headquarters Company proved their value as soldiers and paved the way for future generations of women to join the military and participate in the defense of our nation.

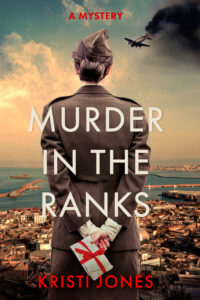

Sadly, for the most part, their stories have been forgotten. I hope my debut novel, Murder in the Ranks, will illuminate their sacrifices, courage, and the critical role women played in combat theaters during World War II. Ike’s girls proved themselves to be invaluable women soldiers who forever changed perceptions on what women are capable of.

***