“Bonjour, madame, and welcome. What brings you to Lyon?”

The man and woman behind the counter at the Hotel de Verdun 1882 looks cool and elegant despite the hot September day. There’s something annoyingly put together about the French, as if they would never condescend to being sweaty or disheveled.

I, by contrast, am both. I have just spent the last eighteen hours on three different trains, traveling from Stockholm to Lyon by way of Hamburg, and then lugging my suitcase from the train station to the hotel. It is only a ten-minute walk, but one of the wheels of my bag has fallen off, making it unusually hard work.

I am warm, uncomfortable and tired when I answer, somewhat crossly: “I’m looking for a good place to kill someone.”

It is the truth, but I’m still not completely sure about my decision to come here. Normally I like to do my killings from the comfort of my favorite chair. Tove Jansson once said that reading is like traveling without leaving your place, and that is also how I like to conduct my murders.

After a possibly too long pause I add: “I’m a writer.”

At this, both the man and a woman (perhaps a couple, I muse. They have that happily married quality of looking at the person they speak to as if they are one entity, presenting a common front behind the counter) perks up considerably.

“But of course!” says the man. “There are so many great places to discover a dead body in this city.”

The woman nods eagerly. “Have you heard about the Fishbones? It’s a secret underground network of tunnels underneath the Croix-Rousse–”

The man continues: “Thirty-two identical tunnels –”

“In the shape of a fishbone! Hence the name. But I’m not sure if they are open to the public?”

The man shakes his head regretfully. Then his face light up again. “But of course! The traboules!”

“The perfect spot!” agrees the wife happily.

I already know about them. They are, in fact, part of the reason why I’m here. I’ve read about the fascinating history of Lyon. But I haven’t been able to see the city clearly in my mind.

Two third of Just Another Dead Author, my murder mystery about a writing retreat that turns deadly, is already written. The majority of it takes place in a fictional and run down castle outside of Lyon. One person had already been killed, right in front of the eyes of Berit Gardner, my writer turned amateur sleuth. So far so good. But for my last murder, I found myself inexplicably floundering.

Lyon is a city of rich and fascinating history. During the renaissance it was the center of a lucrative silk trade. The silk arrived by boat on the rivers Rhône and Saône and had to be carried up to the weavers, protected from the weather at all times.

Lyon is also built on hills, making the small streets steep and tricky to navigate. The solution was a sort of covered short cuts—traboules comes from the Latin trans ambulare, meaning to pass through—where you can enter on one street and come out on a completely different one.

The dark, winding streets of the old weavers quarter seems like the perfect place to die, and I say as much now.

“Let us know if you need any help!” they say. “A few of them are open to public, but others are private and are only open for the postman on certain times.”

In the end, I find a guide who takes me on a three hour, intense, almost running tour of Vieux-Lyon, the part of the city that dates back to the fifteenth century. Afterwards, I return to a small square in the middle of the old silk weavers quarter.

A large mural on one side of the square depicts Guignol, an early puppet theatre about a man who hits authority figures in the head with a large baton, mostly politicians, police and priests. From the square, a small, steep street leads up towards the cathedral Fouverie that looms high over the city. My attention is drawn to a large but surprisingly nondescript red door at 2 Montée de Gourguillon, right in the beginning of the street.

Behind it lies one of the oldest traboules in town. A rounded stairwell leads up, up, up, until you reach a new small courtyard. You cross it, and a new stairwell continues even further.

Residents live here: in front of the doors are doormats saying welcome, and on the walls, signs telling you to respecter les habitants!! It’s a private building, but more than one tourist sneaks up here.

And if you stop and look out through one of the small openings in the walls, you understand why. The rooftops of the old silk weaving quarters spread out before you in a jumble of orange-colored bricks, chimneys, and beautiful, French skylight. Once you reach the end, you’re almost at the top of Fourviére Hill, with its antique Roman theatre and dramatically lit-up cathedral.

My guide tells me that if it was murders I was interested in, a young colleague of his gave a tour of the dark side of Lyon, and he text me later the same day telling me that there was quite a story behind my red door at Montée de gourguillon. Intrigued, I pay the 50 euros for a tour, a find at any price.

The tour features a diverse cast of characters, including, but not limited to, a group of freedom-loving nuns keeping lovers and making a fortune of their many real estate affairs, Nostradamus, a few secrets societies, a group of alchemists, and the French resistance, which used the tunnels to fool the Nazis during the second world war.

And then, of course, there is this story that takes place behind that red door that holds such a strange fascination for me.

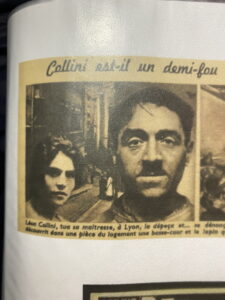

One day, a man walks into a police station in Paris. The first thing he says is: I’ve killed someone. And then nothing more. He doesn’t say another word. No matter what the police asks him. Not his name. Not anything.

Eventually they find a letter in one of his pockets. It’s addressed to his wife, at number 2, Montée du Gourgillon. In the letter, the man confesses to a horrible crime, and begs her forgiveness. The police in Paris call their colleagues in Lyon, and they go over and knock on the door, probably expecting to find the wife dead, murdered by the silent man who now refuses to talk.

Instead, they find her very much alive. She has no idea where her husband is or what crime he’s talking about. Eventually they find out it was the mistress that he killed.

And that wasn’t all. He also chopped her up into seventeen pieces and cast her into large concrete blocks. He had a workshop in the building, and that’s where he did it. The police searched it and found pieces of her.

But not all of them. The head was never recovered.

“And that wasn’t even the weirdest part,” my guide tells me.

“What’s the weirdest part?”

“The workshop was full of rabbits. It was crawling with them. Eventually he told the police why he did it.”

“What did he say?”

“He said the rabbits told him to.”

*

The next day I’m back at the square, sipping my morning coffee.

The door is looked, but I hang around the puppet theatre until a student exits and then sneak in before the large door closes behind her. Ahead of me is a dark and gloomy tunnel, leading toward a bright light. I walk by a row of mailboxes, a reminder that real people live here. Water drips from somewhere, and despite the heat outside, it’s deliciously cool.

I stop when I reach the courtyard and look up. Above me is a gloriously blue sky, framed like a painting by the buildings around me.

It’s a beautiful sight, but also surprisingly haunting; the murky shadows below and the almost taunting sunshine above, the blue sky so close and so far away at the same time.

I knew there and then that it would be the last thing one of my characters ever sees.I knew there and then that it would be the last thing one of my characters ever sees.

As I return to my hotel, the man and the woman ask me if I’ve found the spot for my murder yet.

“Yes,” I say slowly, still thinking about that poor woman, killed and chopped into small pieces. “Yes, I think I have.”

“And is there anything else we can help you with, madame? Perhaps a reservation at one of our many excellent restaurants? We can recommend the rabbit stew!”