“No one knows it’s a horror story when it begins.”

–Mal in Salt Bones

*

At all hours of the night, I would sneak from my bedroom window and dart through the alley, turning either toward the donut shop or through the empty lot where the jeweled date palms dropped their cockroach fruit, across the irrigation ditches that the district mascot Dippy Duck warned us never to swim in (Stay cool in a pool), and beyond the wildflower fields and scrubland to the river where La Llorona roamed—

Whether I’d brought a maple bar and sweet tea or shown up empty-handed, the water kept calling me back, for I, too, was haunted.

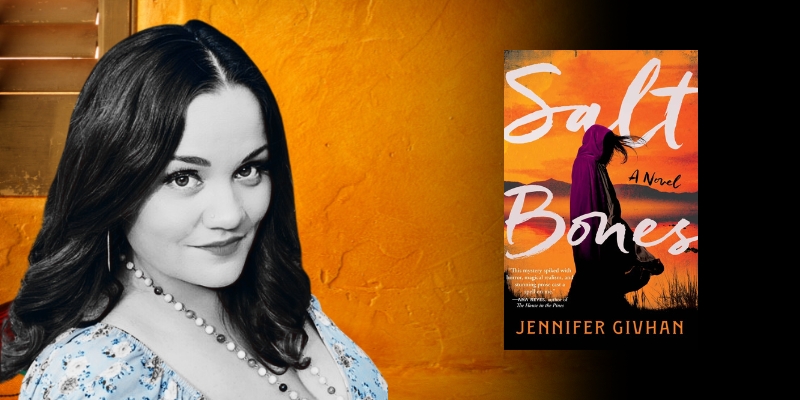

My mother never knew I’d gone beyond my friends’ houses down the street during the day or past the perimeter of my own bedroom at night or the gray hour before dawn. We lived in a small Mexicali border town I affectionately call El Valle in my newest novel, Salt Bones, about Malamar “Mal” Veracruz, a mother-daughter haunted by the disappearance of her sister, Elena, and tormented by the fear that her two daughters will follow their tía into that emptiness.

As Mal navigates the monsters of her girlhood, so too must she contend with the motherguilt and motherfear that come with them.

There were times my mother’s trauma mothered us instead of her, times she should have protected me, but couldn’t. These fractures or twin truths are the root system of my fiction and what I’ve meant to convey in Salt Bones—that a mother can love with her whole heart and still pass down her hurt. Protection can come wrapped in failure.

These fractures or twin truths are the root system of my fiction and what I’ve meant to convey in Salt Bones—that a mother can love with her whole heart and still pass down her hurt.A few years back, I was fetching my daughter from her school pickup line on the Rio Grande bosque; except, when the bell rang and the buildings released their swell, my daughter did not appear. She didn’t answer her phone or texts. All the other kids climbed into cars that drove off. The minutes ticked by, and my anxiety spiraled.

Where was my daughter?

*

When I look back at my girlhood running through the fields, I might praise my wild spirit for rushing to the river every chance I got, or decry my false sense of security; it was not naivety, since by the time I was thirteen, I’d already inherited and experienced trauma. Maybe it was bravado. Or bluster. Or a kind of unintentional healing. All that freedom. All that roaming. The otherworldly continually beckoning—Come. Keep watch with me.

I was a girl vulnerable to the horrors of this world, yes, and I was also something else.

A writer. A healer. A seer. Eyes wide open, heart likewise.

Not everyone sees the girls running free or away from predators night and day on the borderlands. As Salt Bones opens:

For a moment, she’s glowing yellow, gleaming with beads of sweat. Saintly.

Then the gunshots resound.

One. Two. The deafening booms reverberate through the mountains. Aerial drills. Only this is no drill. Following the shots—metal clanks its sick click, click. Boom, click, click. Boom.

If anyone were out here but the night animals, the stars, they’ve shut their eyes. They haven’t seen a thing. They haven’t said a damn word to anyone.

Pero, my bisabuela and tías had nicknamed me La Abogada, the lawyer. I cannot keep quiet about what I see.

*

Cause and effect is the mode of crime and thrillers; Let us show you the underbelly of the world, the broken wheel of justice, the chase and catch. Let us show you what’s wrong, and how it got that way—or how we might fix it.

Braiding poetry and magical realism, I’m after what you can’t quite believe you’ve seen, a trick of the light or misfiring in the brain. Here, events rhyme instead of follow. Correlation hums without demanding causation. And something shifts inside the one who notices.

In many mainstream stories, a missing girl is a trope or plot device. She exists to disappear, like the assistant in the magician’s box. She serves as a metaphor to demonstrate the strength and skill of the protagonist.

I wanted to speak back to that.

As Tana French says in Why Mystery Books are So Satisfying, “In wild mysteries, order isn’t restored, because order isn’t the point. Truth isn’t objective and solid; it’s dark, slippery, double-edged….The questions stay unanswered because they’re unanswerable.”

On the borderlands, truth is slippery and surreal. Our mysteries are not puzzles but hauntings where one girl’s absence shifts the earth and all the girls who’ve disappeared transform the fabric of the universe.

Magical realism stretches wide enough to cling to the strangeness of the world around us, heightening long enough for us to notice it more deeply, allowing everything to bleed and blur, demanding no clean lines, clear delineations, or pat explanations where there are none. Allowing, for instance, imperfect mothers who can fiercely love and protect their children even when they fail to do so, making space for their flaws without demonizing them.

What I love most about magical realism is its compassion. It’s not about excusing harm, but understanding its roots. In my work, I try to forgive what once felt unforgivable—how many times I’ve screwed up as a mother; how my children are safe because of luck, sometimes, not because of me.

“She never acclimates to spilling her girls out into the world. How could she? Daughters disappear here.”

All that motherfear, teaming. Spilling our daughters into the world.

My daughter’s teacher had held their entire class five minutes late, but I was ready to set the world on fire to search for her.

“Mal braces herself, eyes fixed ahead. She’s a hellhound unleashed, barreling toward the brine-swept beach of her youth.”

I write Mad Maxes for brown girls on the Mexicali borderlands, myth-drenched, grief-bright, bone-deep.

And the monsters underpinning our search?

The monsters are not always what we think they are.

I grow weary of crime novels that glorify the human monsters, most often men, or the puzzle-solving itself. The tidy wrap-up or twist for its own sake.

Missing girls and women are not board games or treasure hunts.

In some ways, I realize, I’ve been complicit in the commodifying of missing girls and women. By using the crime fiction mode, I’ve borrowed a structure that can sometimes exacerbate the problem. My hope is that by including my own mother-daughter heart and magical realism, I’ve shaken the mode enough to demonstrate the issues without preaching.

*

“Mal has long worried it’s not only drunkards and womanizers La Siguanaba comes for but children. Teenagers. Girls—everyone blames women when things go wrong.” One monster I complicate in Salt Bones is La Siguanaba, the mythical, shapeshifting woman said to lure men to their deaths. In some ways, she’s every disappeared girl. Every mother’s rage.

But a strange facet of this retelling is how some people believe she takes children, or more specifically, girls, more akin to La Llorona. What is the monstrous mama becomes the central question of this novel, and the ecological and sociopolitical crises unfold from that familial one.

The crime, like the monster, the one I grew up alongside near the Mexicali border, too often goes unseen, disappeared without notice like the girls and women who were never centered enough in the public eye to be missing in the first place. As Laurie Dove says in her debut novel Mask of the Deer Woman, “When Indigenous women disappeared, they disappeared twice. Once in life and once in the news.”

That’s the sleight of hand that narratives about the border perform ad infinitum, convincing the world the real terror is elsewhere. That it’s not an ecological devastation wrapped in colonialism-steeped poverty, where the people are inexplicably tied to the land and vice versa.

A decade ago, when I returned to my hometown with my children, my comadre barbecued carne asada and told me that the Salton Sea had been drying up and releasing its toxic, wind-swept dust, threatening to transform El Valle into a wasteland within the next decade: We’ll all have to leave, she said. It’ll be a ghost town if no one does anything.

Something inside me knew the disappeared were entangled like particles through space and time. The land. The girls and women. The people and our history.

And since I was La Abogada, called by La Llorona, I immersed myself in my predominantly Mexican farming community and the primarily white, wealthy elite who arrived after the late 1800s railroad boom, dividing the land through racist laws and practices. Despite the billions of dollars this land generates for California annually through agriculture, its people endure some of the highest poverty rates in the country.

And yet, so few people have any idea where the Imperial Valley is or how the Salton Sea and the politics surrounding it threaten to destroy not only their precious winter salad bars but an entire community and way of life.

The possibility that everyone and everything I’ve loved since girlhood could vanish and Americans would only notice that they had to eat canned vegetables ignited the same motherfire within me as when my daughter disappeared for those horrifying minutes. I felt a profound responsibility to live up to the high praise bestowed upon my work by Luis Alberto Urrea, who had called one of my books “the Great Mexicali novel.”

I needed to speak up for my homeland again.

Rather than wobble atop a soapbox, I wrapped my ecological swansong in a murder mystery, the very mode I recognize as problematic for its treatment of girls and women as objects, as bodies, as pawns, as mere victims and background.

The crime is not what you think it is. We are all culpable.

*

My work shares the surreality of Stranger Things and Twin Peaks but with a spiritually, politically, and culturally urgent core—Latina-fueled, Indigenous-informed, mother-driven mythology crafted to disturb and protect, witness, and remember…

To chant the names of the girls screamed into the silence of apathy and systemic racism.

What the Duffer Brothers and David Lynch did for small-town hauntings and American subconscious dread, I’m doing for the Mexicali borderlands and my communities where Chicana and Indigenous girls vanish without national outrage.

A fellow writer of color and I once shared stories from our childhoods—his in the Caribbean, mine on the Mexicali border—and we laughed wryly at how readers often called our work horror or fantasy, when to us, we simply write our lives, layered with injustice, folklore, familia, y más. As one of my greatest inspirations and spirit guides, Frida Kahlo, says, “I never painted my dreams. I painted my own reality.”

Myths are not escape hatches; they’re survival maps. I believe crime fiction should not only entertain, but excavate. Not restore order, but reveal what was never orderly to begin with.

I write women who rage and resist—who behave badly because, in the borderlands, behaving often means silence and erasure.I write women who rage and resist—who behave badly because, in the borderlands, behaving often means silence and erasure. Mexican women are rarely allowed full humanity in literature or media. We’re rendered holy mothers or broken bodies rather than complex protagonists with agency and the freedom to make poor choices, then learn from while fixing our mistakes.

In the end, Salt Bones reclaims a woman digging through layers of personal and collective silence to recover her daughter by demanding space in stories that rarely center us. Where Mexican and Indigenous women are often erased, pigeonholed, sainted, and silenced, I offer instead imperfect Latina mamas and daughters living full, embodied lives.

My sleight of hand, my magic, is showing you what’s been in front of you all along, if you only open your eyes—if you say a damn word about it to anyone.

***