There ought to be a word for the particular form of melancholy you feel, upon finishing a book you’ve been enjoying so much you never wanted it to end.

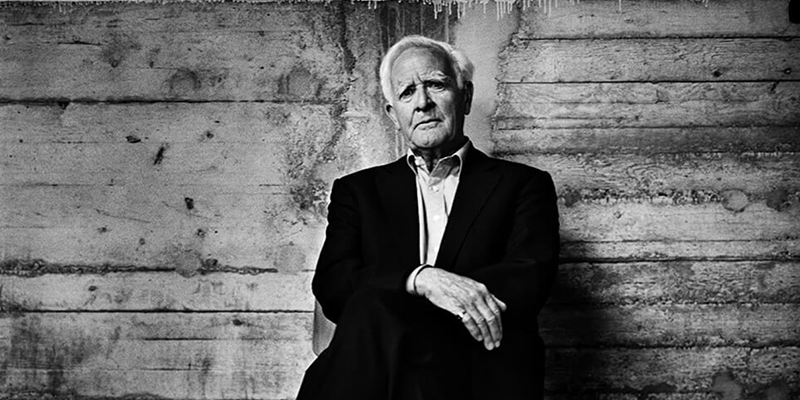

If there is such a word, in some language or other—I’m looking at you, German—then I experienced the extreme form late last year, as I arrived at the hopeful concluding passages of Silverview, a slim 2021 novel about a seaside bookseller in a small British town who becomes entangled with a former spy in a bad jam. That novel, of course, is by John le Carré, nee David Cornwall, and it was quite good—not le Carré’s best, but le Carré’s best is a very high standard, indeed.

What distinguishes Silverview is that it was the last book the master of spy fiction ever wrote (technically, the last one he was writing, because he left it unfinished at his death—although only just barely unfinished, according to a loving postscript by his son, the novelist Nick Harkaway, who completed it posthumously).

For me, the end of Silverview meant the completion of a years-long project I set for myself almost a decade ago: to read all of le Carré’s twenty-six novels, chronologically, from the beginning of his career to the end.

I am hoping this doesn’t sound like some sort of nerdy literary flex, like the guy who read the whole Oxford English Dictionary, or the people who stay up for a whole weekend reading Moby-Dick. I decided to take on le Carré’s oeuvre out of honest enthusiasm, after reading Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy quite randomly. I was designing a course in mystery-thriller writing for an MFA program and realized I had no espionage on the syllabus. Twenty pages in, I felt like David Letterman in that marvelous clip after Future Islands plays his show, and he grins and goes, “I’ll take all of that you got!”

That’s how I felt when I was done with Tinker, a complexly plotted, impeccably crafted, and morally probing novel of Cold War spycraft: I’ll take all of that you got.

What I sensed was that somehow there was much to learn here: much to be excited about as a reader and much to be inspired by as a writer. I started at the top, not wanting to miss anything, and not wanting to allow someone else’s arbitrary rankings to dictate which books I read, in what order.

And so I traveled with John le Carré from the beginning, with Call for the Dead (1961) and A Murder of Quality (1962) two delightful if unremarkable mystery-thrillers very much of their time and place. It is only with book number three, The Spy Who Came In from the Cold (1963) that we can feel the great man becoming great; it is in In From the Cold that he finds his metier, the grubby heroics of Cold War spies, and the sophisticated nuance and drollery of his voice. By the time we get to The Looking Glass War (1965) one has the sense of a true artist, alive in a world he would make his own, adding notes of comedy and world-weary melancholy to his canvass, expanding outwards from the core.

And does he ever, in books six, seven, and eight—Tinker, Tailor (1974), Honorable Schoolboy (1977), and Smiley’s People (1979), the famous trilogy starring the flawed spymaster George Smiley, whose owl-frame glasses and air of heroic melancholy will forever define for me what a protagonist should be: not a hero who is always heroic, but one who tries to be, and never quite can.

And of course, le Carré was only get started.

Indeed, one of the many interesting things I discovered by reading the entirety of le Carré is that his reputation as the definitional Cold War novelist badly undersells him. It was revelatory to watch him develop certain muscles as he wrote his classic Cold War thrillers—in particular his form of complex moral inquiry, a way of seeing all sides without ever abandoning a commitment to simple right and wrong—and then bring those facilities to bear throughout his long, fruitful post-Cold War period, when he turned his searing attention to to, say, Israel and Palestine (The Little Drummer Girl, 1983) or international arms dealing (The Night Manager, 1993) or the slick wickedness of the pharmaceutical business (The Constant Gardner, 2001).

As I approached the end of the list, and the 2000s le Carre gave way to the 2010s le Carre, I was afforded one of the most moving pleasures of my life as a reader—reencountering George Smiley, who we had left behind three decades and a dozen books ago, as he wandered into the pages of A Legacy of Spies (2017), a much older and diminished man, still trying his best to see the world clearly and set it to rights. Much, I like to think, like his author.

Having arrived at the end of this project, I do heartily recommend it, and not just as regards my man John; whoever your literary fave happens to be, start at the beginning and read until you’ve arrived at the end. (It helps, of course, if your fave published or publishes relatively sparingly; if you’re obsessed with, say, Trollope, you may need to quit your job).

What you’ll gain, first of all, is a deeper enjoyment of each individual book, seeing what themes extend from the previous one, and which will be picked up and explored further down the line. What’s to be gained even more so is a deeper, overarching pleasure, of watching this larger entity come into being, this thing called a career, a corpus, emerging as its own text that you can read and enjoy, alongside of and over-top of the individual novels.

I will say that in the months since I finished Silverview, I I’ve experienced some version of mourning. I’m sad not only that the man born David Cornwell is gone, and will not be writing any more of these astonishing books…but also that I’ve read them all, and will never again experience the sublime pleasure of reading a le Carre novel for the first time.

Although—and maybe it’s a coincidence, and maybe it’s a sly plot turn worthy of the master—but shortly after I finished I saw the news that Harkaway will be writing new novels in his father’s style, to feature George Smiley. I don’t think that under the terms of my deal with myself I will be obligated to read these…but somehow I suspect that I will.

***