A well-known exercise designed to expose implicit sexism: you are asked to think of a doctor, a lawyer, a soldier, any number of high-powered and widely lauded careers – and mostly likely the mental image you conjure will be one of a man.

Now turn this exercise on its head. Think of a criminal. Think of a thief, a stalker, a killer. Almost invariably, you thought of a man in this version of the exercise as well.

The American carceral state spares no one its mercurial brutality, but the stories we are exposed to about incarceration are overwhelmingly the stories of men. When we think of incarcerated people in general, we rarely think of women. It’s true that women comprise only 10% of the incarcerated population. One-quarter of people arrested in the United States are women, and women are responsible for 20% of violent crimes and 37% of property crimes committed annually. While these figures position women as a minority within the carceral system, those numbers are hardly statistically insignificant. To compare, people with blue eyes account for 10% of the global population. Surely we can all think of at least one blue-eyed person we know.

Women face unique challenges both while incarcerated and after release – some of which are easy to surmise, others of which more difficult, and all of which are underpublicized. While incarcerated, women experience sexual abuse and coercion so frequently that, in a report about the epidemic of abuse in women’s prisons, Human Rights Watch states plainly “…being a woman in U.S. state prisons can be a terrifying experience.” (One must frankly question if this needed to be said aloud, as if we could not fathom how the misogyny and threat of violence women encounter in everyday life would be amplified behind bars. Women are brutalized and water is wet.) Incarcerated women also receive disciplinary action at a rate that far exceeds their male counterparts.

These woes extended beyond the prison grounds. The unemployment rate of all formerly incarcerated people in 2008 exceeded that of peak national unemployment during the Great Depression. It remains about five times higher than the unemployment rate of individuals who have never been incarcerated. Despite legislative efforts in some states to “ban the box” asking about criminal history on employment applications, discrimination against formerly incarcerated people remains a common practice. Women, particularly Black women, suffer most from this stigma in their job searches, with incarcerated women being unemployed at a rate of six to seven times more than their counterparts who have avoided incarceration. This is to say nothing about the universal challenges faced by all women in the workplace: the gender pay gap, the motherhood penalty in career advancement, America’s appalling lack of maternity leave, the inescapable burden of being perceived as less competent than male colleagues, so on, so forth. Ad nauseam.

In an America that frequently touts its (alleged) commitment to the sanctity of the family, one would also be remiss to gloss over the carceral state’s barbaric treatment of mothers and pregnant women. Three-quarters of incarcerated women are mothers, with two-thirds of these mothers having children under the age of eighteen. Compare this to the roughly 50% of incarcerated men who are fathers. Saying that incarceration shatters families is nothing groundbreaking. Mothers, however, are much more likely to be the sole caretakers of their children, and their incarceration generally visits more far-reaching consequences on their families. Only 18% of incarcerated mothers report sharing their children’s caretaking duties, compared to two-thirds of incarcerated fathers. When a father is incarcerated, his child will likely remain in the care of the child’s mother; when a mother is incarcerated, her child will likely be placed in the care of grandparents or, more frequently than we would like to imagine, in the nightmarish American foster care system.

This cruelty starts earlier than we should be able to fathom. Up to 9% of women in prison are pregnant at the time of their incarceration, and they will receive little to no prenatal or postnatal care. In every state except New York, these women will be separated from their newborns shortly after birth. These women will, of course, likely receive no counseling to help them manage the animal grief a mother-child separation brings – a separation that should break anyone’s heart just to consider.

The crimes of incarcerated women are real, but so is their pain. So is their humanity. Why, then, do their stories remain vanishingly rare in the modern fiction landscape? Even in crime fiction, why do we struggle to center these women?

I have my suspicions. Chief among them is this: we have been conditioned to view incarcerated people are morally black instead of morally gray, and while we abide and even occasionally enjoy morally gray women, we do not like our women morally black, even in fiction.

When I started writing this article, I searched “books about incarcerated women” in Google to see what I could find. Only works of nonfiction came up, most notably the household name book-turned-Netflix-sensation Orange Is the New Black, first published nearly fifteen years ago.

Okay, I said to myself, I’ll change up my phrasing a little. So I typed in “books about ex-felon women.” To my amusement (and frustration), this search yielded a selection of ex-convict romances – and yes, all of the ex-convicts in these books were men. Maybe this speaks to the fallibility of the Google search engine, but I would argue it also speaks to the startling lack of incarcerated women in fiction. Their stories remain all but nonexistent.

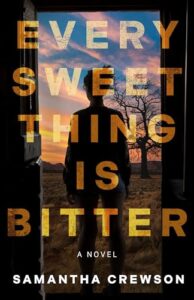

When I wrote Every Sweet Thing Is Bitter, I wanted to look the dark underbelly of female rage in the eye. For me, this meant writing about a woman whose anger went beyond sassy one-liners and being cutely labeled as “stabby.” Women are capable of violence and brutality. Women are capable of the unthinkable. It has been my experience that considering this makes people more uncomfortable than they are willing to admit, and I, for whatever deep-seated psychological reason I should probably plumb further, enjoy making people uncomfortable with my writing. So why not write about a woman who tried to murder her own mother and spent five years in prison for it?

Providence Byrd is a formerly incarcerated women – but like every other formerly and currently incarcerated woman, she is more than the consequences of her crime. She is a devoted sister and friend, a lesbian, a tattoo artist, a survivor. To understand her humanity is to understand that she is capable of violence and hungry for revenge, but also that she feels love, sorrow, joy, pain, and all the other emotions add richness to our world. Like other formerly incarcerated women, her story is layered, complicated, unconventional, and undeniably human.

Women need not be paragons of virtue to have stories worth telling.

***