Though I haven’t lived in New York City in a decade, its grit is in my blood and memories, always making its way into my essays and fictions. Nonetheless, after the malling and gentrification of the Big Apple many believed that the metropolis would be safer, but according to the nightly news the town has returned to the Death Wish days. While some folks tell me the stories are media hype, others have confessed to feeling as though it’s more dangerous than a decade back. This is especially true when it comes to the subway, that infamous “hole in the ground,” where just standing in the station can lead to a being shoved on the tracks, sliced in the face with a box cutter or sexually accosted by some perverted stranger.

Since many native New Yorkers, myself included, don’t drive, the subways are introduced into our lives as babies and are often our primary means of transportation. In addition, it was also a place to meet friends, pick-up girls and read books. I’m one of those people who has passed my stop because of a good book and once had to run off when I thought I was going to be sick after reading the gross Lincoln Tunnel passages in Stephen King’s pandemic novel The Stand.

Living in the Sugar Hill section of Harlem back in the 1970s, our main subway station was located on a 145th Street and Broadway, a few feet away from the McDonalds where Jay-Z used to wait for the Dominican drug dealers to deliver his kilos. That was where the #1 ran.

Back then the station and the subway cars was covered with graffiti. While I was never a “writer,” as the Pilot markers/spray paint artists called themselves, I was a fan of their work, especially the whole car “masterpieces.” More than a few were created in the tunnel between 145th and 137th where a popular “lay-up,” where some subways were parked, was located. As depicted in my 2008 Colorlines short story “Bombing Babylon,” that lay-up was where graff writers from all over the city trekked to create fresh pieces. It also became the stomping grounds for the baseball bat swinging gang the entire neighborhood knew as The Ballbusters.

Though I was a corny Catholic school nerd, I heard Ballbuster horror stories from public school friends about them ruthless Dominican dudes roaming the tunnels smashing limbs and stealing paint from unsuspecting writers. “The Ballbusters made problems for everyone in the 1 tunnel,” graff artist PADE told the website “What You Write” in 2012. “They were a gang of Dominican drug dealers and thugs who lived between 137th and 145th, just upstairs from the IRT #1 tunnel. A few of them wrote graffiti. They didn’t believe in one on one fights, preferring the stomp out.”

Wild style graff writer SPADE 127, who also lived in the neighborhood, was down with the Fast Breaking Artists (FBA) crew who were friends with the Ballbusters. “FBA’s association with the Ballbusters came out of territorial issues and concerns,” he told @149st in 2003. “They were the gang that was directly from the neighborhood that we grew up in; they were heads we had grown up with. We had no beef with them. In fact, they backed us up, and we looked out for them. We had no beef with many writers, but due to the association with the Ballbusters we had a lot of beef.”

SPADE 127

SPADE 127

During that era a pale faced bad boy who lived in our hood named White Mike resided around the corner. He was like Tommy on Power, but not as nice. While his older brother was a suit wearing driver for illegal numbers racket kingpin Spanish Raymond Marquez, who worked out of the Gallery Bar (and later LA Oficina Bar & Restaurant) on Broadway, White Mike rolled with a crew of street punks straight outta a Hal Ellson paperback.

One morning, when mom bought the Daily News at Jesse’s Candy Store, we saw White Mike mean mugging on the cover. He and his homeboys had killed a man on the train the night before. Mike was wearing handcuffs, jeans and a hoodie. “Don’t we know this guy?” mom asked. After I explained that the delinquent lived a block away, she shook her head.

A decade after the White Mike episode, when I was an 18-year-old taking the #1 everyday, I witnessed cool white boy Keith Haring at that same station creating one of his classic chalk drawings on the black space where ads were hung. Occasionally he got arrested, which was crazy when considering the amount of real criminal behavior that was going down in the underground.

One summer evening in the mid-1980s I boarded the subway at 42nd Street and ran into a friend. Robin, a young reporter at the New York Times, was a recent transplant from Detroit and unused to the anything can happen vibe of the subway. Suddenly an argument broke out between two men and both pulled out knives. While everyone made a mad dash to other cars, Robin was frozen in place staring until I grabbed her by the hand, pulled her away and ran. When we got to safety, I shook my head and screamed, “We don’t stand around and watch blade fights on the train. We get the hell out of the way.”

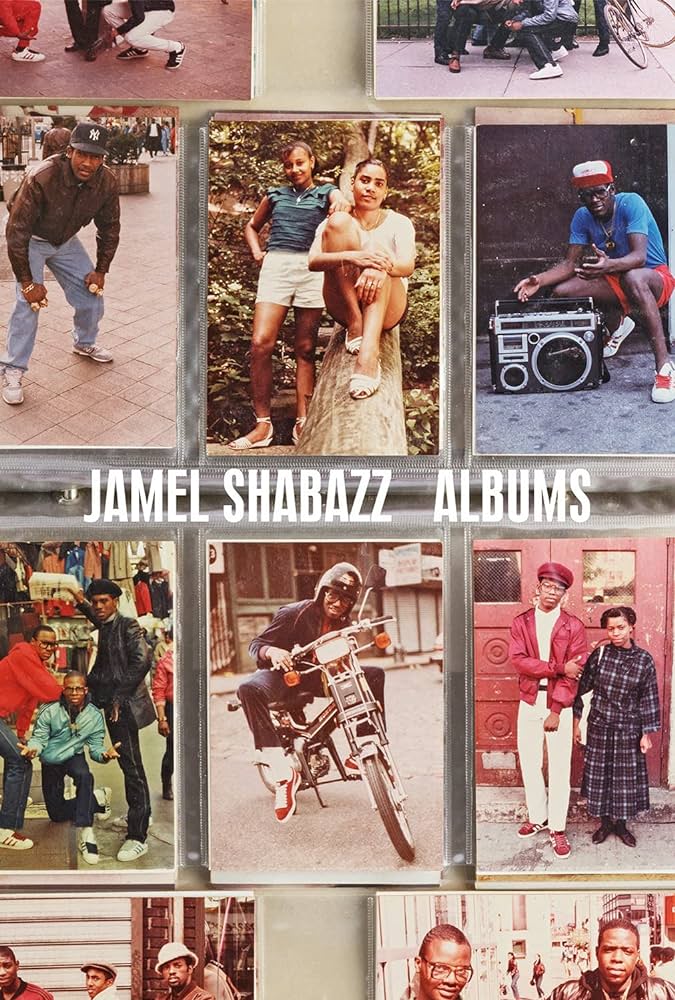

Two New York City photographers whose work I study when writing about yesteryear portrayals of the city are Martha Cooper and Jamel Shabazz, who ventured into the subway system and emerged with visual jewels. While Cooper concentrated on the graff artists and crews in various locations, Shabazz shot young Black folks just chilling in a Brooklyn groove be them packed on a crowded car, styling in the open door or profiling on the platform as he once captured my homeboy Scot La Roc who was with his crew the Ex-Vandals in the mid-1980s.

These were the vibrant pictures I absorbed when I wrote “Graff Art Crime” for the Rock and a Hard Place anthology Under the Thumb: Stories of Police Oppression edited by S.A. Cosby. The story was inspired by the subway station (L train on First Avenue) beating of 25-year-old Michael Stewart at the hands of the N.Y.P.D. in 1983. The battered and brain damaged young man went into a coma and died 13 days later.

Having turned 20 three months before, I felt, as many Black men and boys did–it could’ve been me. Of course the police denied the beating, claiming that Stewart was high on weed and fell down the stairs. As a fellow who constantly rode the rails in the middle of the night leaving clubs and bars in various states of intoxication, Stewart’s story haunted me for years.

My homeboy (and future author of neo-noir novel The Devil’s Mambo) Jerry Rodriguez and I rode the subway together many times, but one night, thankfully, I wasn’t there when he was chased by a few mutant sized rats in the 14th Street station walkway. “Oh my God, they were so big,” he laughed nervously. Back then I often spotted rats on the dirty tracks, but rarely did I see them on the platforms and never did they pursue me through a walkway.

Like me, Rodriguez was a native New Yorker who loved NYC crime films. One night after VHS watching the wild cowboy subway scene in the 1981 flick Nighthawks, featuring ebony and ivory police detectives Matthew Fox (Billy Dee Williams) and Deke DaSilva (Sylvester Stallone) running through the tunnels after terrorist Wulfgar (Rutger Hauer), we talked about our favorite subway movie scenes.

While Jerry opened with recalling the long journey The Warriors took from the Bronx to Coney Island my joint was the cat and mouse game in The French Connection between Popeye Doyle (Gene Hackman) and the Frenchman (Fernando Rey) in Grand Central’s subway station. Later there was the classic car chasing an El train subway scene in Brooklyn that was the cinematic achievement that first made William Friedkin a much beloved director.

At one point in our discussion Jerry brought up the original Taking of Pelham One Two Three (1974), which was, as most people know, a brilliant film about a crew of organized hoods hijacking a subway and demanding a million dollar ransom. Though the film was shot in the ‘70s the train was surprisingly graffiti free, which was a MTA demand thinking that people would think badly of the city if they saw the “tags” on the train.

While that Walter Matthau, Robert Shaw, Héctor Elizondo and Jerry Stiller classic featured a great ensemble cast and the best 1970s theme song that wasn’t in the opening of a Blaxploitation movie, a lesser known train terrorizer was released seven years before. Shot in stark black and white, I watched The Incident one night in the mid-‘70s on The Million Dollar Movie and that haunting film stayed with me for decades.

Subway riders being kidnapped by a band of well-dressed criminals named after colors as they were in Taking of Pelham was slim, but the chances of two crazed loons frightening an entire car of passengers was more likely. The machine gun toting hoods in The Taking of Pelham were on a mission for money, but the crazed duo (Introducing Tony Musante and Martin Sheen) from The Incident were drunk, violent assholes that were “just having fun” by threatening, taunting and beating people who had done nothing to them.

On a quiet Sunday night in the Bronx, they went from harassing a pool hall manager to mugging (and perhaps killing) a random man on the street to cruel criminality towards the passengers on the Grand Central bound train. What struck me as a child was the level of passivity the men displayed; until the bloody climax the hardest fights are the women, with the oldest lady sneaking in with the hardest slap.

We’re introduced to the passengers heist movie style where we meet the characters and hear their mundane conversations before they step into the chaos. The riders included an elderly couple (Jack Gilford, Thelma Ritter), a Black couple (Brock Peters, Ruby Dee), a middle-aged couple (Ed McMahon and Diana Van der Vlis), a teen couple (Victor Arnold and Donna Mills) and a couple of soldiers played by Robert Bannard and Beau Bridges, whose character has a broken arm and was the only non-New Yorker on the train. It was startling how big and bad rapey Tony Goya (Arnold) and militant Arnold Robinson (Peters) were when bullying the women in their lives, but became soft as a Carvel ice cream when confronted with real danger.

There was also one gay character with Robert Fields as Kenneth Otis, “A man whose homosexuality makes him physically ill,” Vito Russo wrote in The Celluloid Closet (1981). “At the outset of the film he tries—pathetically—to pick up a straight man (Gary Merrill) in a local bar and becomes sick in the john. It is a film that, while being repulsive, gives a sense of the alienation that results from being gay in a straight world.” Ken was the third victim (after a sleeping bum and a fresh off the wagon alcoholic played conceivably by Gary Merrill), but he was no more a fighter than the other men.

Director Larry Peerce, a native New Yorker had only made one feature (One Potato, Two Potato, 1964) when he took on The Incident, collaborating with screenwriter Nicholas E. Baehr and cinematographer Gerald Hirschfeld. Though a version of the script was made four years before as The DuPont Show of the Week episode Ride with Terror, I’m sure it wasn’t quite as brutal as Peerce’s.

Method acting bad boys Tony Musante (John Ferrone), revising his role from the original, and Martin Sheen (Artie Connors) were scary, because their characters were more interested in tearing their victims down mentally and emotionally than what they had in their pockets. Musante, who a few years later played now-forgotten TV cop Toma, was even more chilling due to his scary smirk that grew wide as the Joker’s. Sheen was a pretty boy, but Musante appeared really nuts.

Though The Incident hasn’t been written about as much as other New York films, it’s part of a small crop of my favorite flicks, movies that had no problem showing the sinister side of the city. Alongside The Incident that small canon includes Shadows (1959), Strangers in the City (1962), The Cool World (1963), The Pawnbroker (1964) and Who Killed Teddy Bear (1965), films that a later inspired works by Big Apple auteurs Brian De Palma, Martin Scorsese, Abel Ferrara and Spike Lee.

In the real world, I’ve seen similar thug behavior on the subway in the ‘80s that included a gold chain snatched from the neck of a young Latina teen and a bugged out crackhead sitting in a few riders laps. Nobody helped anyone, they just moved away.

The Incident switchblade sliced through sex, stereotypes, class (Jack Gilford ranting about his rich son not giving him money for new teeth is hilarious) and race–Black ain’t beautiful to everybody, especially in 1967. It’s quite telling that when cops board the subway at the end, they first attempt to arrest the innocent, suiting wearing Black man. A year later “Negro” writer Henry Dumas was killed by a policeman in a Harlem subway station.

Filmmaker Larry Peerce would go on to direct a slew of films including a praised adaption of the Phillip Roth novel Goodbye Columbus (1969) and the panned John Belushi bio-pic Wired (1989), but he never made another grimy New York City film, the kind that became so popular in the 1970s. More than two decades after its release, The Incident serves as the telling document of subway crime in New York City, a crisis that ebbs and flows, but will never disappear. No matter how wonderful life might be on the surface, the underground will always be unpredictable.