One night in the 1990s, a Honda Civic pulled up alongside Martin Suarez, who was arriving home after a night out with his wife and their two young sons. “I couldn’t make out any faces,” he writes, “but today, thirty years later, I can still hear the guy’s voice.”

We’re going to kill you, the stranger said before speeding away. Suarez was shaken but not surprised. This kind of thing happens when you try to topple a crime syndicate.

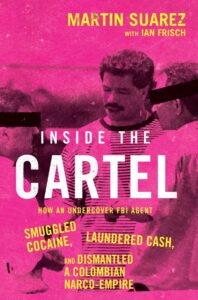

Suarez’s memoir—Inside the Cartel: How an Undercover FBI Agent Smuggled Cocaine, Laundered Cash, and Dismantled a Colombian Narco Empire—is full of gripping scenes. A gun battle breaks out in a quiet neighborhood. A plane ferries bales of cocaine to a boat waiting in the Caribbean Sea. Undercover agents wear wires to risky meetings, gathering evidence leading to dozens of convictions. In the middle of it all is Suarez, whose work, he writes, took hundreds of millions of dollars of drugs off the street.

In a recent video interview, Suarez, who retired in 2011 and was later diagnosed with ALS, or Lou Gehrig’s disease, shared some memories from his remarkable career. We were joined on the call by Ian Frisch, the journalist who wrote the book with Suarez.

*

Kevin Canfield: You were almost killed on the job more than once. The book opens with a hitman trying to murder you in your home. What inspired you to tell the story of your career now?

Marin Suarez: After I was diagnosed with ALS and confronting mortality issues, I figured I would come out with a memoir that would be a legacy for my family. My grandkids, most importantly.

KC: How many grandkids do you have?

MS: Two.

KC: You spent twenty-three years with the FBI. How much of that was undercover?

MS: All of it was undercover in one capacity or another, either running my own cases or assisting other people with theirs.

KC: You estimate that you helped smuggle hundreds of millions of dollars of cocaine, is that accurate?

MS: Over a billion dollars. I stopped counting when I reached a billion when I was researching with Ian. The book covers six years of my early career as an undercover. But then after that, I worked hundreds of cases the rest of my career.

KC: Ian, when you’re working with Martin and he shares a great anecdote, how do you proceed? Do you fill in the blanks by interviewing him as a journalist?

Ian Frisch: Almost, yeah. When Martin and I started conceptualizing the book, I had two questions. Where does the story start? And where does it end? Because I’m not interested in telling a twenty-three-year-long story.

A lot of the FBI memoirs kind of become anthologies of the greatest hits. And I really wanted to try to tell a truly narrative account that had a clear beginning, middle, and end. We quickly realized that the first six years were the most consequential for him and for the agency.

I would fly down to Florida, and Martin and I would sit in an Airbnb for five or six days in a row—six, seven, eight, nine hours a day. And we would just talk through it in as complete a way as you can looking back thirty-something years.

We would have follow-up phone calls, and we got closer and closer to details that ended up on the page. How did you feel in a certain moment? What would it smell like? All the little things that make a scene come alive. That process took us a very long time.

KC: The book circles back to show us what brought you to the FBI, Martin. Your dad envisioned a law-enforcement career for you.

MS: Pretty much everything that led to my career is based on those early years of my dad being such a noble guy. I wanted to be that way.

IF: I really wanted to explore the emotional and philosophical layers of this story. And so much of that was centered on the family. You might come to this book for the swashbuckling undercover adventures, but you’re going to leave understanding what it means for a man to try to do right by his family, right by his country, while balancing this high-stakes, conflict-rich job.

KC: How did you weigh the risks and responsibilities—the work on one side, your family and health on the other?

Suarez: It was quite a balancing act. My family had the hearts of volunteers. They taught me that, from the time I volunteered for the Navy and then volunteered to work undercover with the FBI, they were supporting me.

KC: The loads of cocaine you helped smuggle were seized soon thereafter. But what about the cash that was laundered?

IF: Like Martin said with the smuggling, no drugs ever hit the street. They had these elaborate ruses where the seizure would come at a distant place, so not only could Martin insulate himself, he could also obtain his final payment (from the cartel for smuggling the drugs) and put that money into the U.S. Treasury.

The difference in the two operations was that when Martin was a money-launderer, he actually laundered money for the cartel in a way that that cash went into the underground financial system. That way they could come to understand how the cartel did it. If you seize $1 million from a drug lord, the operation is over. To be able to get the intelligence, they had to actually participate.

KC: There’s been a lot of retrospective criticism of the War on Drugs. That was inefficient, that it didn’t get at the route of the problem—the demand for the drugs in the US. You were extremely brave and stopped a lot of bad guys, but in this broader context, how do you think about your work?

MS: Based on my experience, a bunch of cases didn’t come to fruition not because of our lack of effort, but because the War on Drugs never really started. With some of the presidents like Reagan and (the first) Bush, we see some semblance of the war starting. We were given a mandate to only attack core groups of the cartel at the highest level.

But then things changed over the years, and the support dwindled out. In the middle of operations, they’d call us up to stop and desist, and we’re already in Panama or Colombia. It’s hard to work that way.

KC: You’re a civilian now, but you worked with some scary people. Do you still look over your shoulder?

MS: You can never get rid of that. But not only undercover work. I think soldiers and police officers look over their shoulders, specifically when dealing with bad hombres that have a lot of money to support an operation against you. Yes, I do it, but it doesn’t rule my life.

***