Picture it: Woodstock, Georgia, 1988. I’m at a sleepover party. We’re eating pizza and watching The Amityville Horror and probably drinking Ecto Cooler and jumping around on Pogo Balls because the eighties were wild like that. There are four other girls and one mom hanging out in the living room, braiding each other’s hair, and even though I’m tragically awkward, I’m having a great time. We’re all twelve or thirteen, so being around a cabal of other girls with no boys means we’re safe to wear ratty pajamas and silly socks and play pranks and just be kids, one of our last chances to do so before we’re pushed through puberty like meat through a grinder.

And then the unthinkable happens. A fist pounds on the door, a man’s voice screaming to open up—that he has a gun and he’s going to shoot everyone if we don’t let him in. We huddle together in a corner, five girls in pajamas, shaking, crying, terrified, while the birthday girl’s mom goes to the door and begs the man to leave us alone, holding the cordless phone between ear and shoulder while she calls the cops and fumbles with the safety on a pistol she’s pulled from her purse.

I am certain, in this moment, that I’m going to die.

And then she opens the door, and we all scream, and—

It’s her boyfriend. The whole thing was a setup to scare us as part of the party.

And the mom laughs and laughs and laughs as we cry.

When I think back to that night—and the fact that I’ve never been comfortable home alone ever since—it occurs to me that my lasting impression is one of betrayal. There is a comfort in the company of women. There is safety. On the cusp of teenagerhood, all we wanted was to let down our hair and eat junk food and gasp at an old horror movie, but instead, because somebody’s mom thought it would be funny, and because we thought she could be trusted, five girls were forever traumatized.

because somebody’s mom thought it would be funny, and because we thought she could be trusted, five girls were forever traumatized.First of all, screw you, Terry. And secondly, this horrible memory calls to mind the way that female relationships can open the door for unexpected horror for the precise reason that in the company of other women, we are primed to trust deeply and let our guard down. After all, it’s just us girls. What could go wrong?

In Things Have Gotten Worse Since We Last Spoke by Eric LaRocca, a vulnerable woman forced to sell a family heirloom is approached by a kind benefactress who takes pity on her and only wants the best for her. Whereas men are assumed to always want something from us, to be brash and aggressive and forceful, we women are meant to gently and lovingly support and celebrate each other free of ulterior motive. When another woman tells you, over and over again, that she wants to help you, it can be easy to ignore the fact that her actions don’t support that line. LaRocca’s main character, Agnes, reveals her desperation and weakness early on, and thus Zoe is able to poke and prod her defenses like a snake hunting for a knothole in a henhouse. The softness of her approach doesn’t raise alarms like a different sort of animal clawing at the door. Agnes is slowly, carefully urged to open herself, to change for Zoe, and that is how the horror finds it way inside.

In The Merciless by Danielle Vega, one of my teen daughter’s favorite series and which I read because she wanted to discuss it, a teen girl named Sofia is desperate for friends at her new school, torn between the fun-but-real bad girl, Brooklyn and the holier-than-thou good girls, Riley, Alexis, and Grace. As it turns out, Riley is convinced that Brooklyn is possessed, and the only thing to do—the right thing to do—is perform an exorcism. Sofia gets swept along with this plan, pulled deeper and deeper down the rabbit hole, until it becomes clear that fighting back against Riley and her minions suggests that she, too, is possessed. Sofia wants friends so badly that she’ll do almost anything, and since Riley only wants to help and is literally doing God’s work, there’s no good argument against her actions. Again and again, Sofia’s lines are crossed, but all for the sake of a holy act: to save a friend. Because Riley’s goal is unimpeachable—serving God to fight evil—Sofia can’t push back without implicating herself—and because of the secrecy around the exorcism, she’s left with few resources once she wants out. Of course, at the end, we learn that maybe Sofia had an ulterior motive all along, because sometimes, the prey is actually the predator, lying in wait.

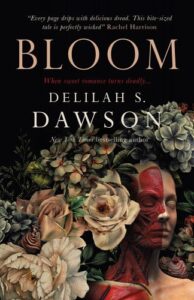

In my own novella, Bloom, an insecure young academic struggling after a bad breakup falls for a seemingly perfect artisan she meets at the local farmers market. Ro thinks she’s straight… until she meets Ash and tastes her pastel cupcakes heaped high with unctuous frosting. Ro isn’t sure if she wants to be Ash or be with Ash, but she is mesmerized by her competency and confidence. Entering her first relationship with another woman, Ro undergoes a stage of transformation and sexual awakening, the emotional equivalent of opening every door in a house for some fresh air, regardless of what might crawl in. Because Ro is exploring new territory with rose colored glasses, she is less likely to recognize red flags, and when something does give her pause, she is quick to explain it away and ascribe only the best attentions to her beloved. She knows what bad behavior looks like in a male partner, but she is unfamiliar with setting boundaries with another woman, especially when such boundaries she feels, should just come naturally. Two women, she thinks, must be on the same side and want the same things. Unfortunately, what Ash wants is compliance… because she’s hiding something in the cellar, something she doesn’t want Ro to see.

In all three books, these intense female relationships push boundaries, spur transformations, and suggest a level of safety and trust that isn’t necessarily present. Much like a screen door that offers friendliness and openness while providing very little protection, such a relationship leaves the innocent party all the more exposed, believing they are safe when in fact, they’ve cozied up to a monster. These bad actors hide behind the illusion of true connection and mutual goodness, all the while creeping over boundaries with soft words and gentle promises, controlling the situation to their own gain. The victim is changed by this intrusion, irrevocably altered at a point of great vulnerability.

The idea for Bloom came to me when my teen daughter fell in love with the Hannibal TV show and wondered aloud why all the hot serial killers were male. I set out to write a book about a female serial killer a smart person would fall in love with—even a smart, straight person who should know better. I wanted to craft a character so beautiful and mysterious that any red flags would be taken for velvet ribbons. In doing so, I had to give Ro insecurities and traumas, and then I had to allow her to be so infatuated that she would accept any lie fed to her with a bite of cupcake. If a strange man at the farmers market invited her out to his lonesome farmhouse in the middle of nowhere, she’d turn right back around and drive home. But because Ash is a woman, and because she projects authenticity and comfort and grace and beauty, Ro interprets her tummy flutters as excitement instead of fear. Ro is not allowed to open the door to Ash’s basement, but Ash is invited to open the door to Ro’s heart, and this invitation is Ro’s undoing.

In Horror, as in real life, a screen door won’t keep you safe. Especially if the killer is already in the house, curled up in her pajamas beside you, braiding your hair and feeding you cake.

***