The action in City Under One Roof, Iris Yamashita’s taut debut novel, plays out against a backdrop of natural splendor and eerie desolation. The fictional Point Mettier, Alaska, is popular with temperate-weather tourists looking for glaciers and mountains. But by the time winter arrives, the only ones left are the town’s 200 or so year-round residents—all of whom live in Davidson Condos, a gloomy apartment building that locals call Dave-Co. There’s just a single road out of town, and come January, snow and ice frequently render it unpassable. The remoteness complicates a criminal probe involving a detective who, at least initially, has more pressing tasks on her agenda.

Cara Kennedy, an Anchorage cop, heads to Point Mettier looking for leads into the disappearance of her husband and their son. In time, she’s drawn into an investigation that begins when a high-school student finds a hand and a foot near a secluded cove. Are the remains from a person who died after falling from a boat? Or has someone been murdered? If so, the killer almost certainly lives at Dave-Co. It’s a subzero spin on Agatha Christie’s every-person-on-the-premises-is-a-suspect conceit. As Cara soon discovers, many of Point Mettier’s residents have secrets—even Amy, the smart teenager who delivers takeout from her mother’s Chinese restaurant, and Lonnie, an eccentric who struggles with her mental health and keeps a moose as a pet.

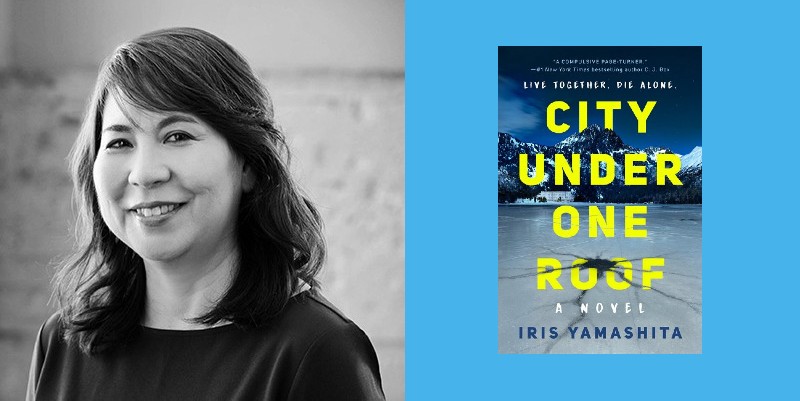

Though this is her first book, Yamashita’s name will be familiar to many movie fans. She wrote the screenplay for the 2006 Clint Eastwood-directed Letters from Iwo Jima, earning an Academy Award nomination. City Under One Roof is the first book in her planned series of novels. Yamashita took a break from writing the follow-up to answer a few questions from her home in Los Angeles.

Kevin Canfield: Your novel has a terrific set-up. It pulled me in immediately. What inspired your fictional town?

Iris Yamashita: I had seen a documentary, probably over 20 years ago, about a town where there was no car traffic in. They had a tunnel, but it was only for the train. The setting was always in the back of my mind: wow, this is a crazy town that’s very isolated, you can’t get through except by train or by boat.

KC: What’s the name of the town?

IY: Whittier, Alaska. I thought it would be a great setting for some kind of story, but I didn’t know what it was until I started thinking of this murder mystery.

KC: And you just tweaked the name of the place a bit.

IY: I didn’t want it to be based on any people there with that small population, or for anyone to think: oh, this is about this person. I wanted to change a little bit of the geography too.

KC: Right, make it your own. Did you always think this would be a novel? Or did you see it ending up on the screen?

IY: I saw it as a television series first. I was coming from the film world and the opportunities in film were all headed toward streaming. I just thought I’d better get a sample out there, being unknown in the streaming and television space. I wrote the pilot (episode). A lot of producers were interested in it as more than a sample, as something to “take out,” as they say in the business.

KC: What does that mean?

IY: Take it out and pitch it (to streaming services). I had a really great director attached at one point. You have to do a lot of work to pitch. You have to know what the whole series is going to look like, and then the possibility of the next season—what’s that going to look like? So I had developed all the characters and the story. Ultimately, we didn’t sell the series, but I thought: I’ve done so much work on this story, let me try writing it as a novel. I found I really enjoyed this process. I wanted to write books before I ever wanted to write films.

KC: Are you a longtime mystery fan? Did you read mysteries growing up?

IY: No. I mean, I read Nancy Drew, but that’s probably it. I wasn’t a huge mystery fan, but I had seen some streaming series that were mysteries that I really got into, and I thought: that’s a great genre, I want to try it. (In a follow-up email, Yamashita cited Top of the Lake and Fargo as TV shows that inspired her work.)

KC: Your characters feel authentic. Can you tell me how you find a character’s voice and the internal monologue that explains their motivations?

IY: When I was thinking about this story, I thought about how the only way in (to the real town of Whittier) was through this train tunnel. There’s a tunnel for cars now, and I visited. It’s a single lane and driving for two-and-a-half miles—it’s a very long tunnel—I had this feeling that I was falling down the rabbit hole and I’m going to end up in a place full of strange characters—people who are quirky and odd. I also felt like if you’re going to go to live in this isolated place, you probably would have some secrets. I didn’t know what everyone’s secret was when I started writing—they just came together. I’m sure a lot of authors say this: the characters start to speak to you. They evolve, and you discover things about them that you didn’t necessarily know when you started.

KC: Can you tell me about the nuts-and-bolts differences—and similarities—between writing for the screen and writing a novel?

IY: For the pilot pitch, you have to know your characters quite a bit. One of my first writing teachers in screenwriting said, “Good characters are those that when you read a line of their dialogue, you know which character is speaking.”

KC: Without even seeing the character’s name.

IY: Yeah, and that’s always in the back of my mind—how do you make their voices distinct? How would a teenager speak? How would a senior citizen speak?

Writing a screenplay is much easier than writing a novel, in that if it’s going to be for a movie, it’s about 100 pages—mostly dialogue, a lot of white space—and if it’s for television it’s even less. An hour pilot would be 60 pages. But it’s harder to have an end product to produce. It can take thousands of people to get something for the screen produced, and a ton of money, whereas a book it’s mostly dependent on the writer. It feels so welcoming and so liberating to write a novel because not everybody is also going to be putting their hands in your pot. You don’t have the director and the producer and the actors involved in the process.

KC: You anticipated my next question. In the acknowledgments, you thank your editors, whose “eagle eyes and questions have enhanced the story in so many ways.” How does working with book editors compare to, say, working with film producers and a director? For instance, did you get producers’ notes on Letters from Iwo Jima?

IY: Yes, a lot of times it is a very frustrating process getting notes in the screenwriting space, because everybody tries to steer it according to their own vision. A lot of times, if they’re not that great with the notes, the producers will just come up with something very ethereal, like “darker” or “more personal”—vague notes that are hard to understand. Others do give better notes, where they’ll say, “This needs a little more comedy here.” Specific notes are always good.

KC: Book editors can’t be vague—they have to dig into the text in front of them.

IY: Yes, they’re trying to help you tell your story. It’s not like they want to change the tone or make it splashier. They’re really trying to enhance the story that’s there, so that is wonderful.

KC: I got a chill—this is true—when I read the last line of the book. I won’t spoil anything here, of course, but I think we can say that it hints at a really interesting new direction for some of these characters in a second book. You’re writing the follow-up now?

IY: I am. Crossing my fingers, it’ll be out in 2024.

KC: Hopefully, this first novel will do well, and all of your new fans will be begging for more and more.

IY: Oh, that would be great.

–Author photo by EF Marton Productions