I’ve met enough crime writers in the past decade to say confidently that a lot of us don’t have much experience with the things we’re writing about. We might know a lot about trauma and injustice, but detective work, forensics, the carceral system—not so much. There are exceptions, of course, but I’d venture to say that most of us rely on research and imagination a lot more than insider knowledge.

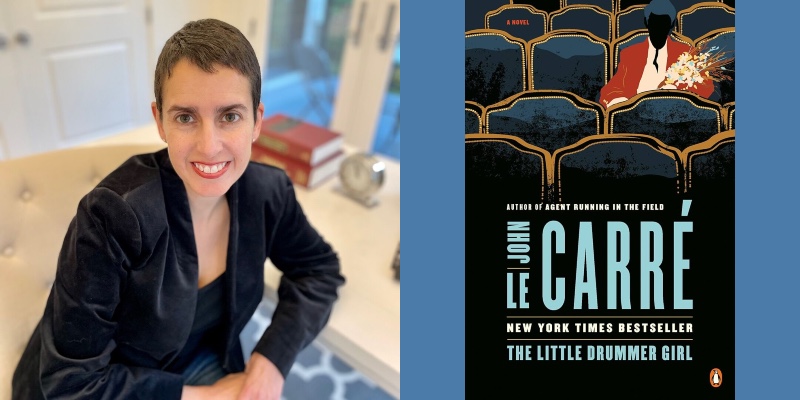

Not I.S. Berry. Her first novel, The Peacock and the Sparrow, drew on her own background as an operations officer at the CIA, specifically her time in Bahrain. It won the Edgar Award for Best First Novel, and—more subjectively—was hands-down my favorite novel of 2023. Recently I got to talk to her about another spy who turned his career in espionage into great fiction, John le Carré.

Why did you choose The Little Drummer Girl by John le Carré?

It’s my favorite le Carre novel. It’s set in the Middle East, which is rare for him, and I think it’s one of his more character-driven books. It focuses on the relationship between a handler, an Israeli spy called Joseph, and his asset, Charlie. Also, as far as I know, it’s the only le Carré book to feature a female protagonist.

I read a lot of online reviews that mentioned the fact that it’s the only one of his books with a female protagonist, but some of them seem to think that the way he dealt with her sexuality was pretty problematic. Charlie sleeps around a good bit, and a lot of her professional choices seem to be motivated by her sexual and romantic feelings about the men around her. Granted, the novel was published in 1983, but do you have any thoughts about that?

That’s so interesting. When I read it the first time, I do remember thinking, “Wow, this girl gets around a little bit.” She certainly seems to be in love with Joseph, but then she also sleeps with his Palestinian counterpart, Khalil. But it didn’t bother me, honestly, and I think it shows the malleable nature of the profession. The CIA doesn’t use honeypots, but Mossad has been known to. So having a woman sleep with someone for operational purposes seemed pretty realistic to me.

I didn’t realize until I started reading that this novel focused on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in the Seventies, but I was amazed by how relevant it felt. Is this a novel you went back to in the context of the current situation in Palestine?

I read it for the first time before the conflict was in the headlines, but it feels so relevant, as you said, and so timeless, like it could be written today. Le Carré doesn’t really take sides or make a moral judgment. He’s showing the ugly reality. There’s a scene about halfway through where Joseph looks in the mirror, and he’s so debilitated. He’s doing an operation where the end goal is an assassination, and what heavier burden is there than that? You see the toll on the Palestinians who are committing acts of terrorism and the toll on the Israelis avenging those actions. What were your thoughts about it?

I agree. It’s not that a moral judgment isn’t appropriate, but I guess I’d say that it’s not the job of a novel to make that judgment. Le Carré thanks people on both sides of the conflict in the introduction, and he’s very clear about the horrific cost of violence to the Palestinians in particular.

I know he did a lot of research, including in training camps. I think he got a lot of things right.

There’s so much in the novel about narrative, and there seems to be a strong suggestion that spying is itself a kind of make-believe or storytelling. Does that resonate with you?

So much of spying is telling a story, and it’s not just how you present yourself. If you’re working with a source and trying to convince them to betray their country, you have to tell them a story to convince them. Whether you’re playing to their vanity or their sense of justice or their love of money or whatever it is, you’re telling them a story in order to convince them to do something. A spy lives their cover, and eventually you and the cover are one in the same. It’s a pivotal moment in operations, and it’s like the moment when, as a writer, you forget that you’re telling a story and it begins to seem real.

Were you reading a lot of spy novels when you worked at the CIA, or did you get into le Carre’s work later?

I didn’t read a lot of spy novels when I was at the agency. I didn’t really make a distinction between spy novels and other novels until I became a writer. I would just read whatever was interesting, and sometimes it was a spy novel, sometimes it wasn’t. I’m pretty sure I read The Spy Who Came in from the Cold after I left the agency. That’s a lot of people’s favorite le Carré, though it’s not mine.

Why isn’t it your favorite?

I don’t think it’s as character-driven as The Little Drummer Girl. I’m so interested in the relationship between handler and source, and you don’t see that as much in The Spy Who Came in from the Cold. There’s really no other relationship quite like it. In The Little Drummer Girl, you see how Charlie and Joseph come to trust each other, but at the same time they don’t fully trust each other. In All Quiet on the Western Front, Erich Remarque describes soldiers as being closer than lovers in a simpler, harder way, and in The Peacock and the Sparrow, I have Collins, the protagonist, say something similar about his source, Rashid. One of the things that makes the handler/source relationship so close is that you’re the only people who know what’s going on. You’re sharing the same risk, the same dangers, and nobody outside that relationship can really understand it. The last scene, where Charlie and Joseph are walking away together, to me it’s one of the greatest last scenes of any book ever written. They’ve literally just collaborated to kill a human being, and no one can understand that experience. It’s a perfect way to represent the fact that they’re in this world that no one else can understand.

I really enjoyed this novel, but for people who are more familiar with modern, action-oriented spy novels than I am, it might seem a bit slow. What did you think about the pacing?

I hear that from a lot of modern readers who don’t love le Carré for that reason. His pacing is slower, and sometimes I wonder if he could even get published today. One of his novels, The Perfect Spy, I couldn’t get through. Some people think it’s his greatest book, but I really found it difficult.

Reader preferences have changed for sure. People have shorter attention spans; they want constant action. They might not want to pick up a slower-paced, more character-driven novel. It’s a challenge for writers, but slower-paced books are my favorite, so I think there’s still an audience for it. I never blinked at the pace of The Little Drummer Girl.

I teach the Victorian novel, so I’m with you—pacing is definitely a matter of taste. It did surprise me here, though, I guess because I was expecting a contemporary spy novel.

Yeah, but the plot is actually pretty simple. We’re following this assassination operation, but there aren’t a ton of twists and turns. With the novel I’m currently writing, I thought of it at one point as a modern version of The Little Drummer Girl, but I ended up moving away from that partly because I didn’t think it would have enough twists and turns for contemporary readers.

Does it bother you when writers get things wrong about the CIA?

Yeah, a little. Then again, there aren’t many of us who have been on the inside, so getting things wrong is probably the only option for most writers. People can do research, of course, but as far as I know, I’m the only current traditionally published American spy novelist who used to be a spy. There’s David McCloskey and Alma Katsu, who both worked as analysts—they have a lot of insider knowledge as well, of course.

There are certain telltale signs that give away if someone knows what they’re talking about. Generally it has to do with tradecraft and operations. Tradecraft is so much more layered than people think it is. In The Peacock and the Sparrow, I have surveillance detection routes nearly on every page, because that’s reality. That’s what you do for every operation, and it’s very tedious. Writers sometimes make it sound like the characters are trying to evade surveillance—like you speed around a corner to lose the tail, but that would never happen. The goal is to detect it, and if you detect it, you abort the meeting. There are no chase scenes, no screeching around corners. If someone has a character talking on an open phone line in a hostile country, that’s another sign that they haven’t done their homework. When characters are scaling roofs or somersaulting through windows, that doesn’t really work for me either. I prefer my spy novels to be more realistic.

That said, I think every writer wants to use a little bit of literary license. In The Peacock and the Sparrow, I have a scene where the characters communicate using invisible ink. People have asked me, “Did you really use invisible ink?” and I say, “No, not once, I got that idea from my son’s science project.” Then there are terms that we used at the agency that I don’t use because they’re just too weird. I refer to headquarters as Langley, but nobody calls it Langley in real life. We call it HQS. We always put an S on the end for some reason, which is weird. Also I refer to the counterintelligence officer as a broom, but nobody refers to counterintelligence officers as brooms. I got that from Graham Greene in The Human Factor. The interesting thing is that le Carré made up a lot of terms too and then they actually became part of insider parlance. Lamplighters is one that comes to mind, and I don’t think people were using the term came in from the cold before he did. But le Carré had so much gravitas that his terms got traction and became part of insider jargon.

Was he still at MI6 when he started writing spy fiction?

I think he was, but it probably wouldn’t have been as much of a problem as it would be over here. I’ve talked about this with my British counterparts, and they don’t have a formal system for getting writing approved the way we do in the US. We have a very formal publication review process for former spies. My understanding is that in the UK, it’s a little more loosey-goosey, but there are informal constraints.

Is there anything else you took from this novel that you might come back to in your own work?

As I mentioned, the novel I’m writing now is influenced by The Little Drummer Girl. The main character is a woman penetrating a terror cell. I think le Carré was a pioneer in that regard, because you never hear about women penetrating terror cells. Also I’m writing about the relationship between handler and source, although in this case, the woman is the handler. That power dynamic is really interesting to me.