Prague in the 1990s was a magical place. Communism had fallen, a seat at the opera cost a few bucks, the city’s magnificence had yet to be sullied by hordes of tourists or chain restaurants. Playwright and former dissident Václav Havel was at the helm, transforming and privatizing and chain-smoking. NATO had opened its arms. In 1994, President Clinton played saxophone at the Reduta black-light theater, where absinthe was served. Statues of Soviet dictators were vanishing. A promise of something was in the air, rising from the city like káva turk steam.

To outsiders, Prague was irresistible precisely for its halfway quality. The feeling that all you had to do was dust off a bit of grime to reveal majesty. That down every alley was something undiscovered, a café or rococo church, whose first arresting view you could claim as your own. Each cranny spawned revelations. The next great thing was just around the corner. You could be the next great thing.

It’s no wonder expats flocked to this new Left Bank. Modern-day beatniks were eager to pan the fertile avant-garde soil; to get a hit of hedonism and a deprivation buzz; above all, to strike literary riches. If you didn’t have a manuscript in progress (or paint, play in a band, smoke, sip brightly colored cocktails into the night), you didn’t belong. Literary salons were de rigueur. The Globe bookstore was perpetually packed, its bulletin board a veritable collage of hopes and dreams.

Full confession: I was one of the flocks. Fresh out of college in 1998, with pots and pans and all my worldly possessions clanging in my suitcase (who knew what would be available in stores?), I headed to Prague on a one-way ticket to try my hand at becoming a writer. The great expat novel, I felt sure, was just waiting for my pen.

In a cheap room above a seedy nightclub called The Roxy, I lived with two Irish roommates. The bathroom was down the hall; the trashcan, wedged between the girls’ beds, served as their vomit bucket; all night long, drunk revelers stumbled past our door, bass from the subterranean bands shaking the linoleum floor. Lucky for me, the dot-com boom was in full swing—thriving in untapped Eastern Europe—and I found work at a startup, the European Internet Network. I edited newswire pieces on emerging economies and nascent stock markets, becoming an expert in transition countries.

Quality newspapers were proliferating in the free-press-starved landscape (Prague Post, originally run by famed journalist Alan Levy, is still around), and I felt I was contributing to the country’s budding fourth estate, gaining valuable editorial experience. My career as an author was surely underway. While my peers imbibed and pontificated into the wee hours, I hunkered down to write.

Eventually, after saving money, I moved to my own flat at Nerudova 47—a cozy attic in the “House of Two Suns”—where, serendipitously, the Czech writer Jan Neruda had lived. (His Tales of the Little Quarter is a whimsical celebration of the Mála Strana neighborhood.) Now, I thought, everything was in place. Living in an attic, tracking news leads by day, watching evening snow settle on a dormer. If this wasn’t the secret sauce to becoming a writer, what was?

And every night, I’d open my journal, waiting for the stories and inspiration to come. From the corner pawnshop, the cellar bar in Žižkov. From my colleagues and their lives and aspirations. From the precise hue when fading sunlight hits centuries-old yellow paint. Images I’d collected were just waiting to be used as literary flats, love nests, hideouts, safehouses. From this city’s rough slab of clay, surely, like Rabbi Loew, I could bring my Golem to life.

It never happened.

Those of us who participated in the great migration now know that Prague in the nineties was notorious for having produced absolutely no notable works of expat literature. (Prague, published in 2003 by Arthur Phillips, is probably the closest approximation—but, despite the title, is actually set in Budapest.)

After less than a year, my infatuation with Prague ended. The bohemian culture was too bohemian. I wasn’t into drinking or drugs, or living in hovels and on leftovers. I wasn’t particularly anti-establishment or angst-ridden. Above all, no story had materialized. Prague had broken its promise to me.

So late one night, when the Cold-War-era radio phone in my Nerudova flat rang, I knew my answer before I’d picked up. Yes, I shouted into the clunky handset. I’d love to work as an intelligence analyst. The connection was bad, but the woman on the other end got the gist. Great, she said. We need someone with knowledge of transition countries. I’ll arrange to have your household goods shipped to England.

A few weeks later, I entered the American embassy on Trźište, just down the street from my flat, where a Foreign Service officer handed me my paperwork. I was headed to Cambridge, England to work as a Balkans intelligence analyst for the U.S. Department of Defense. The move would be easy: just a few pots and pans. My worldly possessions barely filled a suitcase.

Nearly six years later, I would again pack my bags, this time with different items—navigation beads, cargo pants, a compass watch. I was headed to wartime Baghdad for my first assignment as a CIA spy. It would be a harrowing tour, filled with failure, danger, confusion, and heartbreak.

In 2012, I would return to the Middle East, spending two years in Bahrain during the Arab Spring—a movement also filled with disappointment and broken promises.

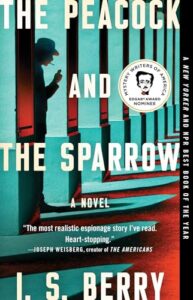

By the time I returned from Bahrain, my suitcase was finally full. I had a story to tell. Last year, my debut novel, The Peacock and the Sparrow, was published. It’s a tale of an aging spy stationed in the Persian Gulf who becomes embroiled in murder, consuming love, and a violent revolution. It’s about expats and their foibles, indulgences, and delusions. It’s the culmination of my years abroad. Two-and-a-half decades later, Prague had finally worked its magic.

Stories, I’ve learned, need more than time and place, more than physicality. They need substance, lived experience, depth. And sometimes you don’t find the story; it finds you.

***

Version 1.0.0

Version 1.0.0