It was February 24, 1995 and I was flying from New York to Memphis, Tennessee to interview soul man Isaac Hayes. As a fan of “Black Moses”—a name that Hayes’ friend and hired gun (literally) Dino Woodard began gave him and Jet magazine writer Chester Higgins popularized the moniker—since I was an eight-year-old bopping to the Blaxploitation bounce of “The Theme from Shaft” in 1971, I looked forward to spending time with the man.

The flight south was two-hours long. Lounging in a window seat, I flipped through a thick folder of Xeroxed newspaper/magazine clips on Hayes and Stax Records, the historic label that launched his career. In the segregated 1960s South, Stax was once an oasis of creative integration where Black and white worked and played together since the day founders Jim Stewart and his sister Estelle Axton took the first two letters of their last names and christened the company in 1961. “We never looked at color, we looked at talent,” Axton often told interviewers.

By 1995, 53-year-old Hayes had a 23-album catalog, three Grammys and an Oscar, but he wasn’t finished. Though it had been seven years since his last album Love Attack, he was more than ready to re-establish himself in a world that had forgotten many yesteryear legends. Although neither of us knew that was to be his comeback year, which would include the Point Blank Records releases of two new albums Branded, a collection of vocal tracks, and Raw and Refined, an instrumental disc, that May.

Five months later, Hayes contributed to the soundtrack of the neo-noir heist film Dead Presidents, the Hughes Brothers’ follow-up to Menace II Society. Released that October, Dead Presidents featured Hayes’ classics “Walk on By” and “The Look of Love,” introducing those songs to a new generation. “We wanted to embrace, transcend and reclaim Blaxploitation while taking it to another level,” co-director/co-writer Allen Hughes said in 2021 while taking a break from shooting the Tupac Shakur documentary Dear Mama. “We needed music that captured the feel, so, when I heard those (Hayes) songs I was like, ‘Yo, this is the movie.’”

Though the Hughes siblings were only 21 when they began working on the film, they were fans of old school soul and well-versed in the greasy grooves that were made before they were born. They gave the cast copies of Shaft, Super Fly and The Mack. “Isaac’s music is cinematic in the way that Ennio Morricone was,” Hughes continued, “we were so happy he signed off on it.” After Hayes signed-off on the usage, the Hughes Brothers contacted him about directing a music video for “Walk On By” featuring him and the movie’s stars Larenz Tate, Chris Tucker and N’Bushe Wright.

“He had my brother and I meet him at the Church of Scientology’s Celebrity Centre,” Allen recalled. Hayes had become a Scientologist in 1993. “We opened the door to the dining room and saw him sitting there. Black don’t crack and he looked the same. We were there to convince him that we wanted to make a video for a song that he’d made twenty-six years before. There was no ego at all, and five minutes later I felt like I was talking to my uncle. He was old school classy, but he had a wonderful sense of humor too. He still had a wicked way with women while still being a southern gentleman.”

Author S.A. Cosby, a fan of Dead Presidents, told me in 2021, “I’ve always felt the placement of the songs perfectly complemented the narrative flow of the movie. There are a few artists who are synonymous with the 70’s and Isaac Hayes is one of them. His songs solidify the time and setting of the movie perfectly.”

Three decades before Dead Presidents, Hayes began his career behind the scenes at Stax Records, where the self taught musician was a studio sideman playing various instruments including saxophone and piano on various sessions before becoming a respected songwriter and producer with lyricist partner David Porter. Stax was the home of Booker T. & the MGs, Mavis Staples, the Bar-Kays, Carla Thomas and Otis Redding, who, in the mid-1960s, was the best-selling act on the label.

Hayes’ first gig at the label was playing organ on Floyd Newman’s 1964 instrumental “Frog Stomp.” Later, when house keyboardist Booker T. Jones went away to college, Hayes subbed for him on some recordings. The following year, Hayes was the pianist on Otis Blue: Otis Redding Sings Soul. “I was scared to death,” Hayes would tell me, “but Otis was one the nicest guys anyone could work with. He had this wild sense of humor that made us all comfortable. Stax was like a family, man. Sometimes I would sleep on the floor of the studio or at the piano.”

Hayes joined creative forces with lyricist David Porter, who he’d known since their teenage days when they attended competing high schools. He had gone to Manassas while Porter graduated from Booker T. Washington. The first song they wrote together was the dramatic “I’ll Run Your Hurt Away” by Ruby Johnson, but it was their work on Sam and Dave singles “Hold On, I’m Comin’” and “Soul Man” that made them a hit making duo. Hayes and Porter penned over two hundred songs in the 1960s, but by the end of the decade he’d grown bored with composing for others, and wanted to transition to the other side of microphone.

His solo debut Presenting Isaac Hayes (1968) sold badly, but a year later he was more successful with Hot Buttered Soul, a groundbreaking album that mixed soul, pop and orchestration. Still, it wasn’t until the Shaft soundtrack in 1971 that Hayes became a crossover pop superstar.

In pictures published in Ebony, Hayes dressed flamboyantly in furs, leather suits, loud colors and miles of gold chains. Larger than life, he looked as though he’d been drawn by Black Panther creator Jack Kirby. However, by the end of the 1970s, Hayes’ fame was fading, his brand of soul wasn’t selling and troubled times loomed.

While he continued to make albums and tour into the late-1980s, it wasn’t until hip-hop producers began using his music that he and the old jams were rediscovered by a new generation. To name a few, Hayes was sampled by The Notorious B.I.G. (“Walk On By”/”Warning”), Mary J. Blige (“Ike’s Mood I”/”I Love You”), Tricky (“Ike’s Rap 2”/”Hell Is Round the Corner”) and Public Enemy (“Hyperbolicsyllabicsesquedalymistic”).

Isaac Hayes was born in Covington, Tennessee in 1942. His mother died when he was a year old and daddy dipped soon afterwards. He and sister Willette were taken in by his mom’s parents Willie James Wade and Rushia Addie-Mae Wade. They moved to Memphis when Hayes was seven, and he had a love/hate relationship with the city since the days when he was a poor boy with holes in his shoes, tattered clothes and an empty belly. As an adult, he often got frustrated with the town and he fled.

“It was the possibility of reform that kept bringing Isaac back,” Memphis resident and writer Robert Gordon, who has written books about the city (It Came From Memphis) and its premier label (Respect Yourself: Stax Records and the Soul Explosion), explained. “He could be an activist, because his voice carried in Memphis, and could have real, practical effect. He was involved in a number of practical social movements like voter registration drives. He became so powerful in the city and in the world, that he could do a lot of good.”

The first time Hayes left Memphis was shortly after Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated on April 4, 1968 at the Lorraine Motel. A mile away from the Stax, the Lorraine was where Hayes and his label mates hung-out, drank at the bar and swam in its pool. After the killing, life in that community changed considerably.

Still, while Memphis gave Hayes plenty of hard times, it was also where he strived, thrived and survived after tapping into the talent that took him far from the tin roofed houses and cotton fields of his youth. “I was born very poor,” Hayes said in 1973. “I didn’t realize when I was a kid just how poor my family was, but as you get older you become aware of it. I’ve seen so many people do well and forget their origins, but I’m proud that I can still go back and relate to the people I grew up amongst.”

After taking that first hiatus in 1968, Hayes returned to Stax and in 1969, channeled his anger, pain and sorrow into making Hot Buttered Soul. “Hayes hit on a psychedelic-era continuation that there doesn’t have to be a boundary between orchestral/symphonic music and funk,” explained critic Nate Patrin. “He took it that further step by allowing for a sense of jamming and improvisation that was a bit jazz and a bit rock.”

***

The morning after I flew into Memphis, I waited for Hayes at the bar in the lobby of the Peabody Hotel. He’d attended a funeral before our meeting, but at the appointed time I watched as he made his way across the lobby wearing sunglasses and a black suit as hotel visitors and workers greeted him like an old friend. He smiled, shook hands and chatted as he made his way over. Hayes greeted me with a smile and slipped his sunglasses into his jacket pocket.

“Who was the funeral for?” I asked.

Hayes chuckled. “It was this white dude that used to work at the Cadillac dealership. About two years after me and David Porter started at Stax, we both wanted to buy Caddies. So we go to the dealership dressed kind of bummy, just wearing dirty jeans and sweaters, and none of the salesmen came our way. They were thinking we just broke Negroes eyeballing the rides. And then this one dude dashed across the showroom to us. Every year we would go back for new cars and the dealers would be like, ‘Oh, Mr. Hayes, can we help you?’ But, we would only give our business to that one guy. I’m sure he was able to send his kids to college from the commissions he made from us.”

Outside, Hayes tipped the valet when the uniformed kid brought back a white Cadillac. Of course, it couldn’t compare to the custom made 1972 peacock-blue, gold-plated Cadillac that Stax president Al Bell bought him after the success of Shaft. It contained a refrigerated bar, a television set, twenty-four-carat windshield wipers, custom crafted wheels and fur-lined interior. The car is currently in the Stax Museum. “We’re just going to drive around,” Hayes said. “I wanted to take you on a little tour of the city.”

Twenty minutes later we were far from the tourist side of town. Hayes turned down a dead-end street and stopped. We got out and for a moment he simply stared at a faded green shack of a house and shook his head. “This house looked so big to me when I was growing-up,” he said. “There was a big fat lady who lived next door who was crazy about me. Her name was Miss Nanny, and she always fed me pig feet, black eyed peas and corn bread. When she died the kids used to tease me, ‘Miss Nanny is goin’ come back and get you.’ It was August, but that didn’t stop me from sleeping under the covers so Miss Nanny’s ghost couldn’t find me.”

Many of Hayes stories, including climbing down the sewers to catch big black roaches to sell as bait and living in another house that was infested with rats, had a southern gothic tinge straight out of Toni Morrison. While we were looking at the house, an older woman stepped onto her neighboring porch and stared. “How you do, ma’am, I’m Isaac Hayes…”

Before he finished the sentence, the lady screamed, “I know who you are. I remember you when you were a little boy…you was a bad little boy.” We looked at one another and laughed. Minutes later, we climbed back into the car and he pulled out of the cul-de-sac. A few blocks away we made a quick pit stop at a seen-better-day’s corner store. Hayes parked in front and we dashed inside.

On the counter were jars of pickles, pig feet and hot sausages. We bought bottles of water, but before we left word had spread through the neighborhood that Isaac was in the store. Boys and girls together were genuinely happy, and a bit surprised, that a real life native son legend was standing next to the cheez doodles.

“What up, Isaac?!” a few young men screamed, giving him a high five while others asked for autographs. Hayes spoke to everyone as he signed scraps of brown paperbags. For some of those kids that would be the best day of their life. With gleeful expressions on their young faces, the kids followed us out to the car.

A few miles away, Hayes pulled into the parking lot besides a massive building. “This is where it all started,” Hayes said, “Manassas High School.” Though he started singing in church when he was five, it was at Manassas where he cultivated his talents. After noticing him hanging around the auditions, a guidance counselor named Mrs. Georgia Harvey convinced Isaac to try out for a talent show.

Shyly walking on stage, he told the pianist to play his favorite Nat King Cole ballad “Looking Back.” Closing his eyes, the lanky teenager began: “Looking ba-a-ack over my life I can see where I caused you strife But I know, oh yes I know I’d never make that same mistake again…” However, that once sweet voiced kid that used to sing during Sunday services experienced a voice change that had gone basement deep.

The song went on for two minutes and at the end Hayes fell to his knees and crooned the last notes. Head bowed, he heard the swoons and screams of a group of girls in the rear. “Man, when I heard them young gals yelling my name, I knew right then and there what I wanted to do,” Hayes remembered. Yet, shortly after winning, he dropped out of Manassas, because he was tired of being broke.

“I was ashamed. I was wearing hand-me down pants with patches and my shoes had big holes in them.” Only in 9th grade when he quit school, he shined shoes, delivered newspapers and bussed tables; additionally, much of his time was spent harmonizing on street corners and drinking cheap wine. Everything was fine until a teacher went to his house and ratted him out. “The next day, I was back in class.” Hayes graduated with honors, but since he’d gotten girlfriend Emily Ruth Watson pregnant he found work instead of continuing his studies.

“I got a job at a slaughterhouse,” he said. “It was a horrible experience. Blood would be dripping down my back and chest, and the floor was covered with guts and shit. At night I woke-up sweating, because I heard hogs screaming in my sleep.” While the couple later married, Hayes continued with his music. Performing with Sir Isaac and the Do-Dads, the Teen Tones and Sir Calvin Valentine and His Swinging Cats, each group struggled, playing gigs in gin mills and juke joints.

“Working in those roadhouses was no joke, it was a man’s game. Sometimes guys would come in shooting up the joint and I had to dive behind the piano. I remember one night a trumpet player was blowing ‘Blues March.’ This drunk stumbled through the door shooting at the ceiling. He screamed, ‘I don’t want to hear no damn bugle! I heard enough of that shit in the Army. Play me some blues.’ Well, we looked at him like he was crazy and played the hardest blues that we could.”

Hayes auditioned for Stax Records a few times before being allowed entry into that sacred temple of sound. However, as he grew in the business, he realized how shady the music profession could be. “When David and I were doing all that work with Sam and Dave, we didn’t realize we were also the producers. Then one night Steve Cropper got drunk and started bragging, ‘Oh, you and Dave aren’t getting paid for your productions, I’m getting paid for mine.’ The next day Dave and I marched up to Jim Stewart’s office and demanded that he pay us.”

From the beginning of his time at Stax it was Hayes’ goal to record a solo project, but co-owner Stewart initially vetoed that idea by telling Isaac that his voice was “too pretty” for soul singing. Finally, he got his chance in 1966 with Presenting Isaac Hayes, though not many appreciated the soul-jazz-lounge songs he recorded with drummer Al Jackson Jr. and bassist Duck Dunn one drunken night in January, 1966. Presenting Isaac Hayes was an interesting experiment, but in no way hinted at the brilliance to come.

In 1969 he released the excellent Hot Buttered Soul. Produced by executive (and future Stax co-owner) Al Bell, keyboardist Marvell Thomas and Allen Jones, Hayes recorded with the Bar-Kays. Hot Buttered Soul sounded like nothing else on the charts and inspired the future shock of seventies soul. There were only four songs on the disc: one original “Hyperbolicsyllabicsesquedalymistic”) and the covers (“Walk On By,” “One Woman” and “By the Time I Get to Phoenix”). Though “Walk on By” was known as a Dionne Warwick number, Isaac made it his own.

The album’s songs were long, the sort of lengths happening in jazz fusion and progressive rock, but hadn’t gotten to soul until Hayes took it there. “For Hot Buttered Soul, I wanted to do some stuff that was outside of the Stax formula,” he said, “You know that I-III-V blues chord thing. I was into all sorts of things including George Gershwin and Burt Bacharach. What I was doing was outside the realm of Stax’s understanding, but the folks listening to the radio were digging it.”

Lush, textured and beautiful, Hot Buttered Soul soon became Stax’s best-selling album. Quickly he recorded two more platinum albums (The Isaac Hayes Movement (1970), …To Be Continued (1970). In 1971, through executive Al Bell’s dealings with the almost bankrupt film studio MGM, Hayes was approached to compose the soundtrack for a different kind of Black movie.

“For Shaft, they already had a leading Black actor (Richard Roundtree), director (Gordon Parks) and editors (Hugh A. Robertson/Paul L. Evans), so they wanted a Black composer and they picked me.” With the exception of Quincy Jones, who’d been scoring films since 1961, it was rare that Black musicians were tapped to record scores for a major film studio, but the then 29-year-old Hayes was up for the challenge.

“I also was a little nervous. I had never recorded a soundtrack before and I was scared that I would mess up.” As a test, Parks gave him some footage and Hayes went into the film studio’s sound lab and composed the iconic theme as well as the vibraphone heavy “Ellie’s Love Theme” and downtempo “Soulsville.” Parks loved it. “It was an exciting time. They turned me loose and let me do it.” Holing up for four-days with the Bar-Kays, the Memphis Strings & Horns and advisor Tom McIntosh, an American jazz trombonist, Hayes cut the music to film in a penthouse studio on the MGM lot.

“The engineer asked to see our charts and I told him, ‘We don’t have no charts, just roll the film.’ We had worked out everything in our heads already and memorized it. The first two days we laid the tracks, the third day we did the strings and the fourth day we put down the back-up singers. I would go sit in my car and write lyrics. We finished a day and a half early.” Both the film and its soundtrack were a hit.

Later, when there was speculation that Shaft’ music would be nominated for an Oscar, some Academy members tried to disqualify Hayes claiming since he didn’t write the music on paper then he wasn’t a real composer. Hayes’ respected friends Quincy Jones and Henry Mancini, who covered “Shaft” in 1972, came to his defense. The next year Hayes became the first Black composer to win an Oscar for Best Song. “I took my grandmother as my date; she was so proud.”

That year Hayes also headlined the concert movie Wattstax. The event was held on August 20th, which was also Hayes 30th birthday. The show, a benefit concert organized by Stax Records to commemorate the seventh anniversary of the 1965 riots in Watts, started at 2:30 pm, but it wasn’t until six hours later when the police escorted Hayes’ car through the gates of Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum where 112,000 screaming fans were ready.

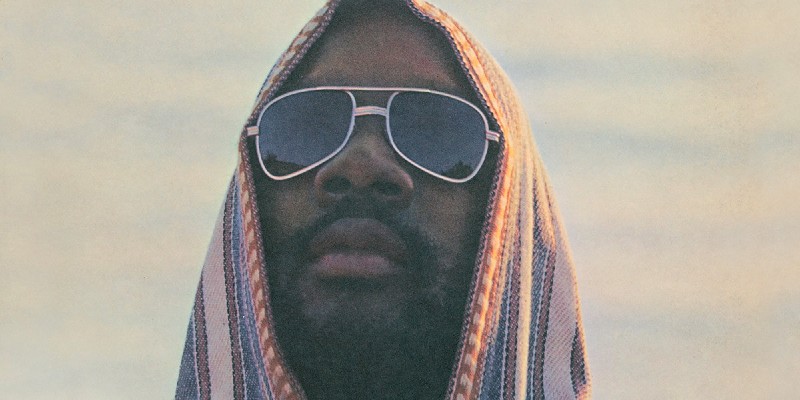

Wearing a multicolored Kaftan, red leather pants and exposing a bare chest draped in gold chains, he was introduced by Jesse Jackson as “the one we’ve been waiting for…a bad, bad brother.” The crowd cheered as Hayes dramatically launched into his explosive set. For the next hour Hayes, the Bar-Kays and back-up singers Hot, Butter and Soul (sisters Pat and Diane Lewis, and Rose Williams) stunned the audience. The film was released on February 4, 1973.

“Isaac was there in all his glory in that movie,” said Allen Hughes. “That whole concert was a grand moment of Black culture, and Isaac was right in the center of the chaos, just being cool and singing his songs.” For the remainder of his career, Hayes became an iconic presence in movies (Truck Turner, Escape from New York), television (The Rockford Files) and a cartoon. A year after I interviewed Hayes, he was cast as the voice of Chef on the popular adult cartoon South Park and played the beloved cafeteria cook for ten years.

In 1974 Hayes left Stax and bought the former Universal Studios (no connection with the entertainment corporation) located at 247 Chelsea Avenue and converted it into his office/recording studio Hot Buttered Soul (HBS) Records. One can imagine how flashy the spot once was, but when Hayes and I drove by twenty-one years later the building was abandoned, the windows were shattered and weeds were growing wild.

Disgusted, Hayes sucked his teeth. It was the only time that day I saw him look upset, as though he was still mad that his HBS Records, which was distributed by ABC Records, hadn’t done better. “I was working on getting my thing together,” Hayes said. “I had a complete band, a few guys had left Stax with me, but most of the crew was new guys.” The label closed in 1977.

***

In 2002 the man from Memphis was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Hayes was introduced by fan and collaborator Alicia Keys, who’d worked with him on “Rock Wit U,” a track from her best-selling 2001 debut Songs in A Minor. Standing at the podium during the induction ceremonies on March 18, 2002 at the Waldorf Astoria, she said, “For thirty-five-years he’s advanced the forms he’s worked in while handling himself with dignity and grace. He’s always cool, always in control and, in a business full of screamers, he knows how to command control with a whisper.”

Six years later, Hayes last big project was the film Soul Men, a comedy that was a tribute to the classic track he co-wrote, the songs of Stax Records and musical memories of Memphis. Starring Samuel Jackson and Bernie Mac, Ike played himself. However, on August 10, 2008, three months before the film was released, Hayes’ wife found him unconscious on the floor next to the treadmill. Pronounced dead an hour later at Baptist East Hospital, he was sixty-five.