Have you ever seen those Progressive Insurance commercials about becoming your parents? Would you be surprised if I told you they inspired a horror novel? Specifically, my new novel BLACK SHEEP. It wasn’t so much the commercials themselves that got me thinking, but the message behind them. Are we destined to become our parents? Can we ever truly separate ourselves from the people and the environment we were raised in? Sever blood ties?

It’s terrifying to wonder how much of ourselves is ours, and how much is determined by DNA. Who among us has not asked ourselves at one point or another (on Thanksgiving, always Thanksgiving) “Who the hell am I related to?” But the horror genre is happy to remind us not all dysfunctional families are created equally. All happy families are alike; every horror family is horrific in its own way.

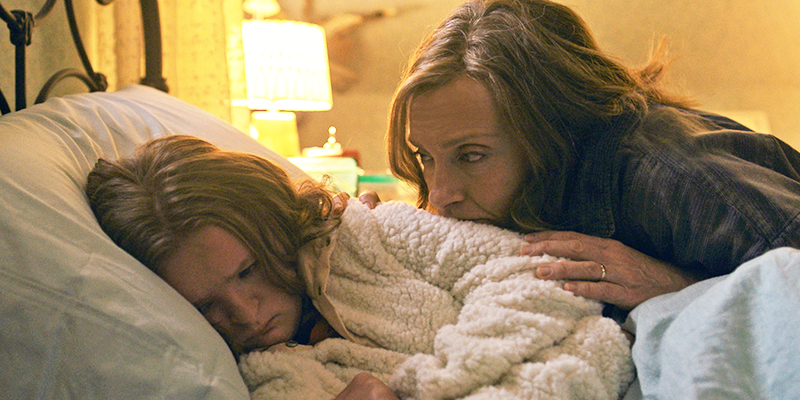

Let’s start with the Graham family, of Ari Aster’s 2018 film Hereditary. Imagine your mother, Annie, is a miniature artist. There’s already a lot going on there. Your dad is Steve, you have a teenage brother, Peter, and a sister Charlie. Your weird grandma has recently passed on, and your already weird home life is about to get weirder. Because turns out grandma was a cult-queen demon-worshipper! And though she may be gone, the rest of her coven isn’t. There’s no giving a polite “no thanks” to the occult. There’s only so much we can do to separate ourselves from our legacies. If you were a Graham, you may choose to skip coming home for the holidays, but not sure opting out of possession is really a possibility.

But at least Annie and Steve are generally decent people who attempt to be decent parents. What if your mother wasn’t Annie, but Margaret White of Stephen King’s Carrie, quick to accuse you of sin and lock you in the closet. A mother who constantly shames you for existing in body and calls your breasts “dirty pillows.” Or Norma Bates of Psycho, overbearing even after her death. A mother who created a harmful, codependent relationship, who is mean and controlling and honestly just pretty annoying overall. There’s a long list of epically bad moms in the horror genre, and I think it’s because of how scary it is to reconcile that the person meant to be your caretaker can be your tormentor.

And then there are the horror daddies. What if your father was Jack Torrance of King’s The Shining, who lets his demons, figurative and literal, get the best of him. The quick pitch of living in a hotel for the winter sounds appealing, especially for a kid, but not if it ends in daddy trying to murder you. Not only that, but through dad, you’ve also inherited a supernatural psychic ability that allows you to see ghosts and have terrifying visions. Not for nothing, I’d take my genetic thyroid issues over the shining. Or what about The Omen. I know Damien is not the most sympathetic character, but what if your dad was Satan? Damien didn’t really have any choice in the matter, did he? Neither did Adrian of Rosemary’s Baby, who we know at the very least inherited his father’s eyes. We don’t get to pick our parents, it’s truly the luck of the draw. We can try our best to forge our own paths, but is it inevitable those paths lead back home?

All that said, you could do worse than Margaret and Norma, than Jack and Lucifer. You could have been born into the Sawyer family of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, or the Jupiter family of The Hills Have Eyes. Imagine that’s the gene pool you were swimming in, one with a whole lot of murder and cannibalism. What if the ugly sweater your aunt gave you for your birthday was made of human skin? The question of nature vs. nurture gets a little more complicated in the context of these families. Were all these people inherently evil, or were they born into an environment that made it near-impossible not to be?

I don’t know the answer. That’s part of the reason why I wrote BLACK SHEEP, to explore these questions and complex family dynamics. Even if there’s valid reason to be estranged from your family—whether it’s because they’re murderous hill people or skin-wearing cannibals or demon-adjacent, or because they’re cruel or callous or their beliefs don’t align with yours—it doesn’t make it any less painful to walk away.

Heredity’s Annie Graham was estranged from her mother. When she discusses their relationship with a grief support group after her mother’s death, Annie reveals her mother had a difficult life. Her husband, Annie’s father, and son, Annie’s brother, both died by suicide. This is perhaps an attempt on Annie’s part to justify her mother’s behavior to better understand or cope with the trauma of her upbringing. But there was also blame. Annie held resentment toward her mother, who she calls manipulative, and in turn worries about blame and resentment from her own family. She grapples with guilt, though acknowledges her mother never experienced any. Her mother wasn’t capable of taking accountability for anything, leaving that burden on Annie. In spite of all that, Annie admits she loved her mother.

In Doctor Sleep, King’s sequel to The Shining, an adult Dan Torrance struggles with anger and alcoholism, just like his father before him. He eventually gets himself sober, but the alcohol was a tool to help him suppress his childhood trauma and his psychic abilities, a tool he now no longer has. Though Jack has been out of Dan’s life for decades, his presence still looms, proving sometimes the scariest ghosts aren’t strangers, but the ones we know best.

There’s no shame in creating boundaries and deciding that maybe the families we were born to aren’t ones we need to belong to. And frankly, I think there can be catharsis in the horrors of somebody else’s bad family. It can maybe help us gauge our feelings about our own. Because hey, no family is perfect. We inherit what we inherit, and let’s just cross our fingers it’s good cholesterol and not Paimon.

And as for becoming our parents, we do have control over that. But please take your shoes off before you come in the house.

***