Set largely during covid lockdown, Sing Her Down introduces Florida, recently released from prison due to issues with overcrowding, thus finding herself with a second chance at life. Pursued by a woman named Dios, also recently released from the same prison, Florida has to reckon with her own past and what the future might hold in a world that seems to be on fire, the pandemic only intensifying the sense of desperation that permeates Florida’s world. Florida skips parole and travels out of state to find her most prized possession, a car she left behind when she was locked away—only Dios, and Florida’s own true nature, can’t seem to leave Florida alone. Sing Her Down proves Pochoda can occupy any voice, any time, any place, pushing her characters to the type of reckoning that would make Flannery O’Connor proud.

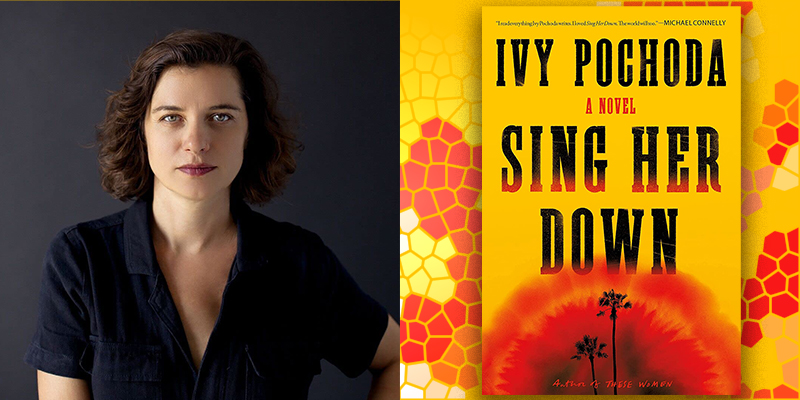

Ivy’s brightest gift is her ability to morph into anyone and anything, occupying a different type of person as easily as she might cover any landscape, making her home in any and every fictional universe imaginable. Sing Her Down is Ivy’s most brilliant work yet, and Ms. Pochoda shows no indication of stopping her rise any time soon. Ivy, who found a natural home in crime fiction with Visitation Street, sat down to discuss with me how she fell into crime fiction, a genre which suits her spectacularly well, especially in answering the questions which interest her most, and exploring the people she wants us all to find a part of ourselves in.

Matthew Turbeville: Ivy, I’m so excited to interview you for CrimeReads. I have loved your fiction since reading Visitation Street. You have a voice that’s so distinctively yours, much like Megan Abbott, Alafair Burke, and Attica Locke. Which writers have most informed your writing and shaped you most during your formative years? Which books and authors do you continue to turn to for inspiration?

Ivy Pochoda: I think the book that inspired me most now is Fortress of Solitude by Jonathan Lethem. Jonathan and I are different in age, but he grew up two blocks from where I grew up. When I was first trying to write, I thought you had to write super wild imaginative, made-up books, and I tried to write these super wild books, and then I read Fortress of Solitude. I found out you can write a book about your neighborhood, and you can make it poetic and beautiful, and take the small things that occur to you on a daily basis and turn it into art and fiction. It sort of changed my life. I went from trying to invent crazy, wild stories to writing more closely observed fiction about what was going on outside my window. For me, that was a game-changer.

Ivy Pochoda: I think the book that inspired me most now is Fortress of Solitude by Jonathan Lethem. Jonathan and I are different in age, but he grew up two blocks from where I grew up. When I was first trying to write, I thought you had to write super wild imaginative, made-up books, and I tried to write these super wild books, and then I read Fortress of Solitude. I found out you can write a book about your neighborhood, and you can make it poetic and beautiful, and take the small things that occur to you on a daily basis and turn it into art and fiction. It sort of changed my life. I went from trying to invent crazy, wild stories to writing more closely observed fiction about what was going on outside my window. For me, that was a game-changer.

I reread Jesus’s Son by Denis Johnson routinely. There are small moments in that book where he has the most poetic and beautiful observations about gritty things and finds the most beauty and joy in the most desperate and down-and-out characters. I look at those two books quite a lot, and at Zadie Smith’s NW. I admire her amazing use of dialogue and language and flexibility with form. I love how she summons that neighborhood in northwest London, which is something I do and something Jonathan clearly does. Also, it’s no secret that I reread Blood Meridian a lot!

There are also so many new books I’m inspired by—one example is Julia Phillips’ Disappearing Earth. I love seeing how she stacks all those stories together into a novel.

MT: You write crime fiction, which is such a great match for your gritty voice and your ability to slip into worlds outside your own. Has your fiction always had such a crime fiction slant? What do you feel is so inviting and enticing about crime fiction, and how did you make the move into writing in this genre?

IP: It was a complete accident. When I wrote Visitation Street, had been inspired by Fortress of Solitude and wrote about something outside of my window, and at that time I was thinking my book was a combination of this and Carson McCullers’ The Heart is a Lonely Hunter. To my surprise, when it was sold to my publisher, they told me it was crime fiction. I thought I was writing straightforward literature, and my editor asked me, “Well, what did you think was happening? You wrote a book where two girls go missing on page one, and you find out what happens on the last page—that’s a mystery.”

Back then, I didn’t know anything about the crime community. I thought I was going to be marginalized and no one is going to respect the writing—not the story, but the writing. I feel like it’s the luckiest thing that has ever happened to me in my writing career. Win awards, write a best-seller, who knows, but the fact that this book moved me into the crime community is the best thing that’s ever happened to me. The people! I went to the Edgar Awards recently, and the love in that room, for everything from cozies to hard crime to procedurals, it’s the most supportive community out there. Obviously, it has some problems. We need to do better with representation and embracing diversity and new voices, but it’s way ahead of where it used to be and other genres. I love crime fiction because people love to read it and it’s not a chore, and people embrace it. It gives you the flexibility to mess around with tone or structure or form, and it’s super fun. It doesn’t necessarily have to be cut and dry murder and white guy PI who solves it! Now we can write about all sorts of things, and the crime doesn’t have to be the center of the story.

MT: It really feels like the crime fiction community is a family.

IP: It really is.

MT: I love the idea that you write fiction that allows women to be as violent as in the fiction of authors like Cormac McCarthy. It helps dispel this notion that women don’t have a certain violence to them, and it steers clear of the only violence from women appearing in movies where actresses like Charlize Theron wear make-up and fat suits in order to play a villain. But even in your novel, characters like Florida change their names to allow themselves to slip in and out of this more chaotic, sometimes sinister world. What is the importance of allowing Florida to move in and out of her own violent persona, and how do you avoid the notion that women who enact their own forms of violence must necessarily become villains?

IP: I feel like one of the things that’s in this book, not in Florida but in Dios’ character, is code-switching. Dios is a Latina girl from Queens, who is given a scholarship to a really ritzy predominantly white school, and from there, she has to negate her sense of self, which is not why she’s violent, it’s just something that’s happened to her. It’s funny you bring that up about Florida, because she’s also code-switching. She feels like to be safe and survive in prison, she has to pretend she isn’t that person that she was before she committed these crimes. The secret is she is that person. To survive, she has to dissociate, and she is not able to embrace who she really is and almost allows this persona to be created for her.

I’m glad you brought up Monster because we are so able to embrace violent women if they are violent because men have done something to them. We only can understand women’s violence if it’s put through a male gaze or male lens. I wrote my thesis in college on Macbeth and Oresteia, and when Clytemnestra kills Agamemnon or when Lady Macbeth commits various acts of violence, the vocabulary that the playwrights use is very anti-maternalistic—“unsex me now,” “rip this baby from my breast”—there’s no baby! When Clytemnestra is talking about her strength, she is framing it as the nurture has been ripped from her. We can only talk about this by keeping men in the picture or keeping women rebelling against their feminine nature in the picture, and we love Aileen Wuornos’ story because she is a prostitute and she has been raped and men have done this to her. We love stories where women have been attacked or their kids were taken away from them by a man.

We forgive violent women if their violence is inspired by some original male violence, but we cannot deal with violent women who are violent under their own sail. It’s infuriating to me. These women exist, but we never tell their stories.

MT: One of the most compelling aspects of your writing is your ability to inhabit multiple voices all at once. Reading your work is an amazing experience, where I’m looking to engage with multiple characters who are beyond me, but finding some of myself in every character. When you write, how do you go about tackling the different voices and narrative strands of each character to keep them individual and distinct?

IP: Let me tackle that in two parts, because it’s really interesting what you said about identifying with yourself in every character. That’s exactly the point. I want to go back to Visitation Street. When I wrote Visitation Street, there was like all these different characters: a drunk white musician, a Black girl who’s getting in trouble at school, and others. What I thought when creating these voices is how they’re all having a problem or there’s something going on in their lives, and I had to figure out how I would react in those situations. I put a little bit of myself in all of them regardless of race, class, gender. I found something that they were reacting to, like the failed musician—I put some of my own disappointments in there—or the girl who is having issues with her best friend, which is really about me growing up. Identify with yourself in every character, that’s exactly the point.

These people are not nonfiction–they are fictional people–and I do like to have a whole cast of characters people can find points of identification with. Someone like Dios, who is both from a disadvantaged background and goes to a ritzy college, is beautiful, violent, well-read and misunderstood. The reader should be able to find one thing they can relate to, whether it’s “I went to a fancy college” or “I am misunderstood” or “people deny me my strength because I’m a woman,” and there are all these things that make up a person. We should have more empathy for people in our lives, so I like to create characters who are fully rounded so we can find points of identification in them.

Now, as to the voices. There comes a point in your writing career where you can say, “I can just do it,” and I can just do it. I remember Jennifer Egan talking about A Visit from the Goon Squad, and she said, “I went running and I ran, like, eight miles and I forgot to pick up my kid from school and the whole plot appeared to me,” and I thought, “bitch, you’re lying!” But the voices just come. This book is a little less voice-heavy to me than my other books and these voices change. I was really inspired by Blood Meridian and that open ending, and there’s this distance in this voice, and I sort of wanted to make it Dios’s voice, so that voice just started talking to me one night, and that sounded like an kind of overly educated person who’s a criminal, and I kept listening, thinking of what she would be saying, riffing on Blood Meridian in my head as if a woman was narrating it.

When creating voices, I give every character one thing they’re obsessed with. So, Dios is obsessed with Florida and women being denied their own power, and Florida has her obsession about the car and the tree. I circle their voice around their obsession, and I can sort of find them.

MT: I remember meeting Jennifer Egan at a literary festival and I remember her saying something along the lines of how she rarely wrote from a woman’s point-of-view because she didn’t want her own self to bleed into her characters—and I love that you do not seem to give a shit about that.

IP: It’s funny you say that because Wonder Valley only has one woman in it, and when it came out, I got a lot of pushback on that book. I was in conversation with Megan Abbott, and she asked, “What are you doing next?” My agent was sitting in the front row, and I sort of had These Women in my head, but it wasn’t about women, it was about people surrounding this serial killer. I remember saying, “I’m going to write this book” (and my agent was so worried about the all-male thing in Wonder Valley) “and it’s going to be all these different women’s voices around a serial killer,” and I remember thinking, “Fuck, now I have to do this, and I’m not good at writing women,” and I wasn’t. The women’s voices in Visitation Street are young, they are in their teens, and that I can do that. But with These Women, I remember thinking, we need to go really deep into voice. Like with Jennifer Egan, the characters are going to be inspired by things I’m thinking but I don’t need my character in these voices. And it’s so hard!

MT: I remember reading that Toni Morrison often wrestled with characters and their voices, ones who wanted to be heard much more than she wanted to permit them to be present on the page. Do you ever wrestle with characters who may want to take over the page or even over a whole novel? How do you tame the voices that are so commanding for your readers?

IP: Julianna’s voice in These Women was the easiest part of that book for me, and I had no problem writing it and could have gone on forever. Dorian’s voice, which opens the book, was really hard, and I kept working on Julianna and writing more of that perspective but had to make it balanced. So, when I can hear somebody like that, I understand her outlook on the world. I knew she wanted to take pictures. I knew she didn’t understand why some art was more valued than other art because she’s wondering why her pictures would never be shown in a museum like Larry Sultan’s work—a photographer who shot behind the scenes of porn shoots. Julianna’s voice was really powerful, and Dios talked a little too much in earlier versions of Sing Her Down. I had to peel it back because the danger with Dios talking too much is that I don’t want to explain her or justify what she is doing. I just want her to do it, so I had to have her talk less so I didn’t get into any explanation or back story of why she’s doing what she’s doing.

MT: Do you write all the scenes with certain voices at once, or are you able to go back and forth?

IP: I can go back and forth, but I try to write them in complete blocks. Like in These Women, I wrote all those sections fully, and then I went back and edited them, just because I want them to tell their complete story. But with Visitation Street and Wonder Valley, I have alternating shorter chapters, so I can go back and forth.

MT: Do you have any specific methods you use to go about writing outside of yourself?

IP: I try to find something in each character that is me. When I was writing about Skid Row in Wonder Valley, that’s very much not just inspired by but about the people I worked with in Skid Row. I try to tell their story but not make it mine. I try to respect wherever the story is coming from. I don’t know if that gives me permission to do it. I try to find a story that I feel comfortable telling about my characters, what they are going through, but I’m not speaking to the whole experience of whatever race, culture, community that person comes from.

MT: Moving from each of your books to the next, they’re all completely different. When you write a book, you’re truly setting out to write something unique and individual. Are there any rules you have to avoid writing something you’ve done before? Are there characters you want to revisit in future books?

IP: I revisit Ren from Visitation Street. He is in Wonder Valley, has a one-second shot in These Women, and he’s the muralist, although is not named, in Sing Her Down. My characters live on. I teach my students that these people don’t end when the book ends–try to think of them existing in the world after the story you’re telling about them concludes–and I think that makes it easier to write the book and they stay alive for me. Jonathan Lethem and I had a conversation about this, and he said, “hell no, when I’m done with a book, these people cease to exist.” I can see it both ways. But my characters—and some of them are dead—live on in me. When I start thinking of a book, it often has something to do with the previous book.

Recently, I started writing something that I’m not sure I’m going to use. Blake from Wonder Valley was living in Mexico by himself, and I wrote twenty pages about him. I think I’m going to use it in my new book, but maybe not. One problem I have writing a new book is I often feel like I’m writing my last book, and it takes me a while to get out of that.

MT: What do you think is the most important point of writing a novel, especially a crime novel?

IP: I think it’s different for different books. I often don’t know the full story of my book when I set out to write it, but I like to think of my books as a three-dimensional panorama, with all these different perspectives looking at a single event. It’s figuring out how to build that sphere, and I like to create a community of characters to see how they interact. For me, that community of characters is the most important thing.

MT: When you write, do you start with the crime or the character, the setting or the story?

IP: Character and setting for sure. I had no idea what the crime was in this book. Wanted to open with a super violent scene of women being violent in prison and that’s all I knew. And that’s not the crime in the book, it’s just some other act of violence. Then I figured out what it was about.

MT: I remember reading that scene and thinking, “Wow, I love this, but oh my gosh.”

IP: I thought long and hard about that, but said, “Let’s just go for it.”

MT: What are you working on now? What’s next for the great Ivy Pochoda?

IP: I’m writing a short story now, then writing a horror novella based on The Bacchae, and I also have an idea for a novel that I hope to start in the new year. I thought I was going to wrap up writing about Los Angeles with this book, but I thought one more. It’s darker, but it’s also a more about love and family and apocalyptic violence.

***