Something that looked like a sea urchin was growing on the office door. I hadn’t noticed it at first because it was the same dark brown color as the wood but on closer inspection, the tendrils (I called them tendrils because I didn’t know what they were) looked like they were dusted with a fine powder. I had an urge to reach out and touch them—they seemed spongy and inviting in a weird kind of way—but I didn’t. Living on a tropical island had taught me that much.

Growing up in New England, nature was, for the most part, bucolic and unthreatening, thanks to a few hundred years of farming, hunting, and logging. I’d walk for hours in the woods, hardly seeing any wildlife, and the only things that bit me were mosquitoes. Then living in concrete Californian cities like Los Angeles or Oakland, what little nature existed was conscripted to landscaping or parks, with maybe an occasional rectangle of hardened dirt along sidewalks so long as the roots didn’t mess with underground sewage pipes.

On Maui, nature was bountiful, beautiful and it had teeth. Something I learned the hard way within the first five minutes of getting out of the cab in upcountry Maui. I saw a slow-moving chameleon and picked it up only to discover that while its legs moved slowly, its head moved quickly, and it locked onto the thin skin of my wrist with its tiny but powerful jaws. I, Dorothy, wasn’t in Kansas anymore.

More lessons followed. Ignoring the warnings of posted signage, I waded into knee-deep water off Makena Beach, and a powerful rip current yanked me off my feet and thrust me into what felt like a washing machine, filling my lungs with ocean water. Discovering a gecko in the house, I tried shooing it into a glass like a spider—it detached its tail and ran off with a bloody nub, and the tail wriggled on the floor for a good minute after. After that, I let them be. I scoffed at the notion I’d need to dress warmly to watch the sunrise at the top of Haleakala—I was a Yankee, after all, used to harsh winters—and found myself shivering in my thin jacket, blowing on my hands to keep them warm until the sun came up over the horizon, revealing an otherworldly landscape of Mars-like rocks and cinder cones that made me feel like I’d landed on another planet.

Eventually I came to grips with the idea that what I knew wasn’t applicable to where I was. So I took things slower. I observed more carefully. I listened more than I spoke. In the process, a kind of inversion began to take place and I began to get glimpses of my own strangeness, the peculiar qualities of my culture.

Like looking directly into people’s eyes, which I’d been taught to do as a sign of confidence, but in Hawai’i could be considered aggressive, hostile even. My determination at work to have meeting agendas and a timely start when what was more important was to talk and build relationships because a community can accomplish more than a hierarchy. Careless consumption seemed especially egregious when I saw tourists behaving as I used to, treating the island as just another Disney-esque entertainment venue, an opportunity for selfies before getting back on the plane, leaving their trash behind.

And then there were moments when the line between real and the surreal began to blur, which is harder to describe, but every once in a while, I’d run into a place or a thing that held a certain kind of magnetism that could attract or repel, an undefinable quality that felt like another world bubbling beneath the ordinary.

Driving on the back road to Hana, high up on the hill, I saw a gnarled, half-dead tree with a commanding presence. I felt like it was watching me—glowering almost—and I would have pulled over to hike up to get closer, but there was no turnout. But I still think about that tree. One time my husband and I thought we’d go see the lava fields that hug the coastline, but as the road turned to dirt, the feeling that I wasn’t supposed to be there, that we needed to turn back now was so overwhelming it almost felt like a panic attack. So we turned around, and as soon as the tires hit pavement again, I felt my breath begin to ease.

And then on the back lanai, I found a gecko that was perfectly still, the tip of its tail a bright white. It looked at me with its big, orbital lizard eyes, I looked at it with my oval-shaped mammal eyes, and I felt compelled to sit down next to it. It didn’t move except to blink. Gradually the color drained from its entire tail, then its lower body, then its upper body, then its neck, then its head. Going, going, gone. I gently picked up its white body, and it was like holding a dead leaf, or a piece of paper, light and dry, while all around me the sun shone, and the wind rustled the palm fronds. I realized how simple and easy death could be. Just another natural transformation.

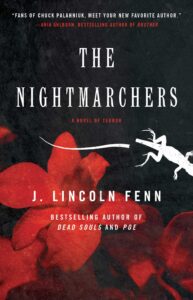

Many of these elements crept into my novel The Nightmarchers, and maybe this is what draws writers to islands—when we press our hands in the dirt of the unfamiliar, we can see ourselves and our periphery more clearly. Because nothing that I saw or experienced was unusual to someone who grew up there. I was the interloper looking in.

As was my sea urchin office mate, which turned out to be the fruiting body of a brown slime mold. Stemonitis splendens, a single-celled mass that can function like a brain—in fact, slime molds can solve mazes. How did it get there? Most likely, crawled. I decided not to disturb it. Or maybe it decided not to disturb me. So while it slowly digested the damp wood of the door, I focused on my work. Each of us inhabiting a single space, and our own, mysterious worlds.

***