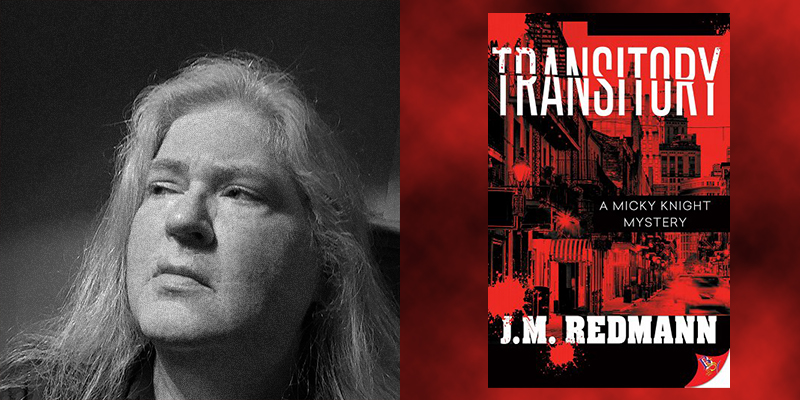

The late 1980’s is a long time ago—it’s also when both Ellen Hart and J.M. Redmann started writing mysteries with lesbian protagonists. At the time many states still made queer sex illegal, and marriage was likely to happen after pigs found wings and soared aloft. Hart’s first book, Hallowed Murder was published in 1989, and Redmann’s Death by the Riverside in 1990. Both were able to break into so called mainstream presses, Hart with St. Martin and Redmann with W.W. Norton along the way in their careers. They have each won multiple Lambda Literary Awards, as well as numerous other awards. Hart was named a Grand Master by Mystery Writers of America, one of the top honors for crime writers. They got together to talk about Redmann’s new book, the 11th in the Micky Knight series, Transitory.

EH: Jean Redmann has been one of my favorite crime writers since I first came upon her novel, The Intersection of Law and Desire, in a bookstore in DC while I was on a national book tour. The flight home was delayed, but it didn’t matter to me because the mystery was so compelling that I barely looked up. When I first met Jean in person, I was already a huge fan. Since then, we’ve become friends and I count that friendship as one of the many blessings crime writing has brought to my life. Here’s just a taste of her thoughts on writing and the writing life. I once heard P.D. James get asked a question that resonated with me. (It also annoyed me.) The interviewer said, “You’re a fine writer. Why mysteries?” The subtext was, you’re good enough to write literary novels. Why waste time with genre fiction? The same question could easily be asked of you.

J.M.R.: Thank you, I greatly admire P.D. James. It’s a question that is stuck in the hierarchy of art—classical music is better than hip-hop; the old masters are better than pop art. Literary fiction is better than genre. What are the assumptions that underlie this hierarchy? It would take a book to unpack them, but think about class, power, money and control. I call bullshit on them all. You can like different things, but don’t confuse you’re liking with it being better. A book is a good book if it finds a reader who enjoys it. For me, I wanted to do mysteries for multiple reasons—to shift the iconic hero of the mystery to be a lesbian, assert we can be heroes and the ones who defined what justice is; crime novels can deal with some of the starkest human conditions—the shock of murder, the hollowness of loss, how do people move on after that. I’ve never felt constrained by writing mysteries.

E.H.: Mickey Knight, your protagonist, is one of the richest characters in all lesbian mysteries. How did she come to you? Are you like her, not like her?

J.M.R.: First of all, not at all like her. She has the advantage of being rewritten and edited, unlike the rest of us. She started out in a short story when eventually became the first book, Death by the Riverside. Once I had committed to going beyond the short form, I had to dig down and consider what would make a woman, a lesbian, decide to become a PI? What makes someone a loner, causes them to search for justice? Like a childhood where you didn’t have it. I wanted her complex, messy and a bit of an asshole; that was what makes her interesting to write. For the story arcs I wanted her to be able to change, to grow, mess up, learn from it and search for who she was, what she wanted, and how to settle for what she could have.

E.H.” When you started writing, what made you decide to write about an out lesbian? What risks did you face? What did you hope to accomplish?

J.M.R. Duh, I was a lesbian. Also, it was possible in a way that it hadn’t been for earlier generations. There was an explosion of women’s culture, the music festivals, lesbian record labels, magazines, journals and the women’s presses that started publishing books that featured us—Firebrand, Naiad, New Victoria, Seal. It was gloriously possible that I might write a book with lesbian characters and, albeit by a small press, see it published. There were also women’s and LGBTQ bookstores. There was a community there for us. I didn’t think about risk—I lived in NYC at the time, worked in theater and my parents and grandparents were dead. I started fooling around with short stories. Somehow the one with the lesbian PI in New Orleans captured my imagination and interest and it became a novel. (Amateur mistake, you can see it in the structure of the book—we learn as we write.) I didn’t know that I had goals much beyond to amuse myself and possibly a few of my friends. And put a lesbian in the south. Most of what I was reading were set in the North East or West Coast. I wrote the first book, threw it out into the world and had no idea where it would land. If anyone would read it. I had no goals of being a best-selling author; it didn’t seem remotely possible for someone writing in the queer world (and sadly still seems to be the case—there are lesbian authors who do quite well, but not for their lesbian books). If I had a goal at all, it was to the write the kind of book I wanted to read.

E.H. If f someone is coming to your novels for the first time, should they start at the beginning? Is there one book you’re most proud of?

J.M.R: Every book is a different journey; we write them when we are different people. That past person is gone. The first two I think I was playing, putting the words for the joy of taking those 26 letters of the alphabet and creating a world that no one else would create. I also felt like I only existed in the queer world, was a lesbian writer, not a mystery writer. Those first two were more influenced by the lesbian novels of the time—more sex and romance required—less so by mystery. My third book, The Intersection of Law and Desire, changed that. 1995. A major NYC publisher (W.W. Norton). An actual advance. A very good editor who taught me an incredible amount. A beautiful cover. Copy editing that also taught me a great deal. Reviews—Maureen Corrigan from NPR liked it! Made it to the front page of the living section in New Orleans’ major newspaper, the Times Picayune. I also felt I was a better writer by then. I’d seen my earlier mistakes, learned from them (I hope) had a clear idea of the characters and what I wanted to do with them. It won the first Lambda award, picked as an Editor’s Choice for the year from the SF Chronicle. It was the book that convinced me I could do this, could be a writer, could write the next book and the one after that. I have tried to write the books to be read without having to read the earlier ones. There may be some backstory hovering around, but the book works even if you haven’t read earlier ones.

E.H. You have a great line in Transitory, your newest mystery. “New Orleans is a city with a dream that stopped at a bar along the way.” The sense of place in your novels is so strong, so evocative, that it almost feels like a character. It reminds me of the way Raymond Chandler wrote about L.A., or Dennis Lehane about Southie. You see it, taste it, smell it. It’s not just a place, it’s a mood. Not just background, but context. Do you see it that way? How critical is the New Orleans setting to your writing?

J.M. R.: New Orleans is so evocative, so different and unique, a setting that influences the characters and plot. I didn’t grow up in New Orleans, but my father was a native. His father, who died long before I was born, was a bar pilot on the Mississippi. He was stationed at Pilot Town, at the mouth of the Mississippi, and boarded the large ocean-going vessels entering the delta. The river is so complicated with currents and sand bars, it took someone who knew the river to pilot the boats up to New Orleans. I grew up about 90 miles to the east in Ocean Springs, Mississippi. Even though it wasn’t New Orleans; it was still the French-Spanish part of the country. We often went to New Orleans—I’m probably some degree of cousin to every Redmann in the city. New Orleans was the big city, the place so much bigger than our small Mississippi town, it loomed large in my seeing the world for the first time and my imagination. There is a way that you know the light, the smells, the sounds, when you come to them as a child. Even though I was living in New York City when I wrote the first book, it just seemed natural to set the book in the city of my childhood imagination. I had already moved to New Orleans before it came out and lived there for over thirty years. I will always consider it the city of my heart and soul. It is a city that has survived and decayed and rebuilt again and again after flood and fire. I really wanted to convey New Orleans, the history, the haunted streets, the joy of jazz, the contradictions of a city that can create the greatest party in the world, Mardi Gras, and not fix the potholes, the city that creates great food and music, writing, and the city of slavery, segregation, grinding poverty. In the back of my head, I’m always wondering how people in New Orleans will judge what I’m writing about the city. You have to get it right.

E.H.: Do you create your stories by outlining? If you don’t use an outline, how do you construct a plot? How important is plot in your novels?

J.M.R.: I don’t create an outline before I start writing. I think, like most authors, I have a story idea in my head first. After my brain churns for a while, it comes up with something resembling a road map—by the time I start writing I know where I’m starting, about where I’m going to end up and some stops along the way. The actual journey is writing the book. I outlined my first book and from that learned that I don’t pay attention to outlines. I didn’t work for me. Sometimes characters stroll in and take the story in a different direction. Or I come up with better ideas of how to make it work. Plot is always important in mystery novels—I’d say in most novels. We’re asking our readers to let us tell them a story. I think character drives plot. If readers care about the characters, they care about what happens to them and where the plot takes them. I’m also writing first person with Micky, so I stay in her head for most of the book; I think that makes it easier to not have an outline. Other books, like yours, that shift multiple points of view probably need an outline just to keep track of who is where doing what.

E.H. Do you have a favorite Mickey Knight novel? If so, what is it—and why?

J.M.R.: As I mentioned earlier, if I had to pick a favorite, it would be Law and Desire, because it marked the change from me being a dabbler to being a writer, at least in my mind. But it’s hard to pick a favorite book. Death of a Dying Man was half-way written when Katrina hit New Orleans. The city I had been writing about no longer existed. I made the hard decision to write that in, how it impacted all the characters—the entire city had to evacuate, so everyone was physically affected—and how it changed the plot line. I felt I needed to bear witness to what had happened. That continued in Water Mark, titled for all the dark lines left, still showing where the water had reached. The new book, Transitory, was interrupted because I had to have cancer surgery and radiation (so far, no sign of recurrence) so it was also a struggle to get it to the finish line. Depending on the day, my favorite might change. Or maybe it’ll be the next one.

E.H.: Will there be a new Mickey Knight novel in the near future?

J.M.R.: TRANSITORY is out September, 2023. I have to write at least one more, if only to leave the series at an end point. But I’m not sure. I haven’t started anything yet and may work on some other projects along the way, but am mulling some ideas.

E.H.: What are you working on now?

Mostly promoting Transitory. I have developed a bad case of carpal tunnel and am still waiting on surgery on the second hand, so am typing more slowly these days. Luckily, this is fixable, but it can take time to get both hands done and healed. I’m playing with some short stories and other ideas, but nothing formed enough to talk about.

E.H.: What surprised you, both negatively and positively, about becoming a writer?

J.M.R.: It’s a lot of work! If you’re serious and professional or aspiring to be, you have to learn the rules. For a long time, I had the Chicago Manual of Style on my desk and consulted it quite often. Learning (and still learning) to self-edit, to kill the darlings, to stare at the page looking for the right word and to realize inspiration doesn’t get you through a novel—it’s sitting alone, giving up free time, to put the words on the page. The positive side is that there is a great community of writers and readers out there who support your work. Yeah, there are assholes, but for the most part I’ve found my tribe, especially with the queer crime writers.

E.H.: Were there any writers (books) in your past that inspired you to become a writer?

J.M.R.: All of them. The not-so-great books spurred me to think I could do that. The great books told me what wonders could be created with mere words. The women who wrote books when women weren’t supposed to write—Jane Austin, the Brontës, George Elliot. The queer writers who claimed space on the page—Rita Mae Brown, Dorothy Allison, Alison Bechdel (fun fact—Alison and I studied karate together when we were young and living in NYC, so I can say I have punched her). The mystery writers—Dorothy Savers, Ngaio Marsh, Agatha Christie, Raymond Chandler, Emma Latham, P.D. James, Sue Grafton, Sara Peretsky, so many others. The queers who wrote mysteries—Joseph Hanson, Barbara Wilson, Sarah Dreher, Katherine Forest, Mary Wings, Ellen Hart—the first out lesbian to be named MWA Grand Master (that would be you) Michael Nava, Greg Herren, Anne Laughlin, Jessie Chandler, so many others. And I’ve left a huge number out.

E.H.: Who is your favorite detective in mystery fiction? Your favorite mystery?

J.M.R.: Jane Lawless, of course. She is one of my favorites, the way she grew and changed in the series. But the truth is that it is so hard to say. There are so many. Trixie Belden and Nancy Drew when I was younger. If I had to pick one writer, which I would hate to do, it would be P.D. James.

E.H.: Any advice for aspiring writers?

J.M.R.: Be serious and professional. Don’t guess at grammar; look it up. Distracting editors with your eccentric use of commas isn’t how to get published. Don’t trust your friends when they tell you it’s good. They’re lovely people, but unless they are publishing professionals, them telling you it’s a great book doesn’t mean it is. Get in a writer’s group, or something that can give you more rigorous feedback. Read! Widely and broadly, but also read a lot of the books like the one you are trying to write. Write because you want to write, not because you want to be a writer. You control the words you put on the page. The rest of it, being published, reviews, awards, is controlled by someone else.

E.H.: Many, if not most, lesbian mysteries today have an element of romance in them. How important is that to your novels? (I probably shouldn’t ask if Mickey and Cordelia will ever get back together, but of course I do wonder.)

J.M. R: I think most of us have—or want—an element of romance in our lives. As I evolved as a writer, I realized my interest was in the central quest of the mystery—how do we seek and find justice, who gets to define what it is? That said, I try to make Micky as real as possible and a messy personal life is part of that. Will they get back together? I don’t know yet. I don’t know where Micky is going on the next part of her journey. Guess you just have to keep reading the books to find out . . ..

E.H.: What challenges you most in your writing?

J.M. R.: We writers are tasked with creating a world with words. One of my challenges is to do my best to tell the reader what they need to know, to walk the fine line between being obvious and obscure—telling them too much or not enough. What words can I use to convey the impact of a murder, to show a physical fight as brief and brutal as it often is? One editing exercise I do is to see if I really need that word? Why make readers take the long way when you can give them a shorter way to get there? I tend to write long books (Transitory is a little over 90,000 words) so I need to take time and effort in making sure I use the best ones I can. Also, confronting the ongoing pitfalls—did I write a good book? Just because I have in the past doesn’t mean I have this time. Speaking in public, not making a fool of myself. All the places we take risks and might fail.

E.H.: Do you see themes emerging in contemporary lesbian fiction? What, in your opinion, is missing? What’s taboo?

Last first, you can’t kill the cat. Or the dog. As to the first, even if I read most of the day, it would be impossible to read enough of the lesbian books now published to discern a theme—except that we are real, full people and deserve our stories to be told.

***