The crime was a shapeshifter from the start. But in the early hours of March 13, 1964, its parameters seemed clear enough. A rape and murder. Harrowing, but not outside the purview of our darkest imaginings. A young woman, Kitty Genovese, coming home from work at 2:30 a.m. after her shift at the bar, assaulted outside her apartment building in Queens, New York.

Yet within days, the crime had evolved. Rape and murder, yes, but something else, too. A new, sinister spin that cast a treacherous pall from Queens to all five boroughs. Beyond the horrors of sexual assault and homicide, the Kitty Genovese story morphed into a tale about the apathy of New Yorkers writ large. Of the purported 38 people who “witnessed” the crime – who lived in Kitty’s apartment complex, who heard her screams but did nothing while a rapist and murderer fled the scene, only to return half an hour later to finish the job – not a single one intervened. In the weeks following the event, the more insidious transgression, it seemed, was that New Yorkers were a brand of callous urban spectator who wouldn’t lift a finger to save you if you were literally being murdered on the sidewalk in front of them.

In the ensuing decades, psychologists, ethicists, and anyone interested in the more egregious realities of human behavior circled Kitty Genovese like sharks to chum. Soon, another narrative took shape. Kitty Genovese wasn’t merely a crime of rape and murder. It wasn’t just a story about 38 New Yorkers who stood idly by. No, it was a cautionary tale about our stunted human instincts, our deep and abiding reluctance to intervene for a whole host of complex reasons. Not only did the murder give rise to a national emergency phone number, 911, but also to a new social-psychological vernacular. Bystander Theory, Diffusion of Responsibility, and Pluralistic Ignorance were part of the emerging lexicon.

For as long as I can remember, I have been fixated on this crime. Perhaps it is rooted in my own hazy memory of hearing a woman scream in the middle of the night when I was seven years old. We were staying at my mother’s childhood home in Salinas, California, all of us piled in her old bedroom. The window was open, warm night air wafting in. I lay awake, insomniatic as usual, staring up at the ceiling when I heard the scream. It was full of urgency and terror. I shot up in bed and looked around the room. No one stirred. I remember feeling a mixture of fear, powerlessness, and hesitation. Untrusting of my own instincts. Unwilling to make it real by waking up an adult. If it happened again, I told myself, I would do something. It did not happen again, and so I did nothing. The memory—of both the scream and my nonintervention—has haunted me ever since.

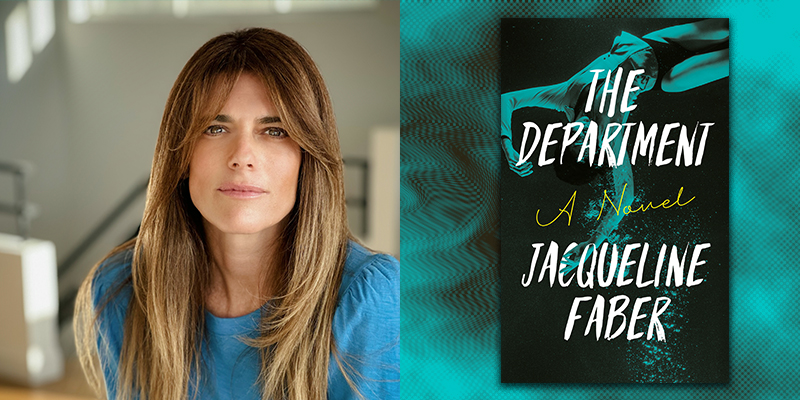

I imagine it’s why I imbued one of the protagonists of my psychological thriller, The Department, with a pathological aversion to ever being a bystander. When a college girl goes missing at the university where Neil Weber teaches, he’s drawn into the mystery of her disappearance. But the deeper he delves into her story, the more unsavory discoveries he makes about his own colleagues in the philosophy department. Along the way, we learn that Neil is tormented by a memory of his own inaction during a childhood trauma. It’s no surprise that he, like me, is preoccupied with the ever-shifting terrain of the Kitty Genovese tragedy. The spectre of the bystander hovers over him, exerting its demands and shaping the course of the narrative.

In reality, the Kitty Genovese story did not stop with the emergence of a new social-psychological paradigm for understanding human behavior. Because in 2015, Bill Genovese, Kitty’s brother, released a documentary called The Witness. It was an attempt to peel back the layers of his sister’s murder and understand how 38 people could do absolutely nothing while she lay there dying. The Witness laid bare yet another version of this shape-shifting crime, which had already accumulated so much meaning. A story of rape and murder. A judgment on the apparent indifference of urban dwellers. A reality check on our natural proclivities to remain on the sidelines. And now, a disturbing revelation about the harmful role of the media in shaping this narrative.

Through his in-depth research, Bill Genovese learned that the initial stories of inaction were greatly exaggerated. Several neighbors did try to help, and at least one, Sophie Farrar, held Kitty in her dying moments, blood smeared on the stairwell beside her. He learned that many neighbors didn’t understand what they were “witnessing,” catching only fragments of the crime, an errant scream, a shuffle in the hallway. At the time, 911 did not exist and the local precinct was slow to respond to phone calls that came in during the attack. If The Witness shed new light on the crime, it was, in part, by unveiling the media’s role in whipping up a clickbait furor that treated the 38 witnesses and not the dead girl as the object of interest.

As I write this, we have just passed the 61st anniversary of Kitty Genovese’s death. So many iterations of a story that continues to exert its morbid fascination, its dark intrigue. I think about the theories to which Kitty Genovese gave rise (which are not, by the way, bankrupted by the inaccuracies of the initial reporting). Decades of psychological research have borne out certain ineluctable truths: that we do tend to outsource responsibility when there are other witnesses present. We believe that others are more qualified to handle an emergency, better prepared to respond than we are. We calibrate the seriousness of our own reactions by the seriousness of the reactions around us.

One of the starkest differences between today and 1964 is the frequency with which we find ourselves in the role of the witness. Social media alone turns us all into potential bystanders, potential interventionists. Navigating this boundary between the two feels more complicated and fraught than ever. I don’t purport to have any answers. In a way, Kitty Genovese has always been burdened by the quick answer. The willingness of outsiders and voyeurs to proclaim their understanding. To consider the case closed – both on the murderer, Winston Moseley, who died in prison in 2016, but also on the meaning of the event. Perhaps the best we can offer the memory of Kitty Genovese six decades on is to hold space for a continual rewriting, acknowledging our proprietary instincts to stake our claims, at the same time, resisting the allure of such finality.

***