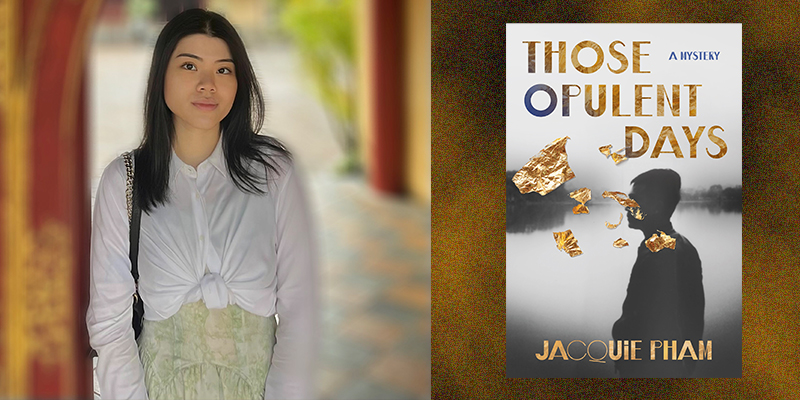

A historical mystery set in 1920s French-colonial Vietnam, Those Opulent Days is the debut of Vietnamese-Australian author Jacquie Pham. The novel opens with a death, and the prophecy that foretold it many years before.

Four friends, close since childhood when they attended the same exclusive boarding school, have become Saigon’s most powerful elite. As they gather in a lavish mansion in Dalat for an opium-fueled evening, one dies mysteriously. The novel’s following chapters alternate between that fatal night and the preceding days, peeling the layers of conflicts and loyalties that might have led to the death.

Written in precise, elegant prose, Those Opulent Days explores the many imbalances that wealth, gender, and power wield. While delivering a solid mystery, this novel touches on issues of colonialism, racism, queerness, sexual violence, addiction, and more. It’s certainly not a light read, but it’s an engrossing one, illuminating a time period in Vietnamese history that may be unfamiliar to most readers.

I connected with Pham via Zoom — her in Sydney at breakfast time, me in Washington State the previous afternoon! — to discuss her debut, its themes, and the politics involved.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Jenny Bartoy: What inspired this novel?

Jacquie Pham: The idea came to me after a very long reading fog where I wasn’t interested in all the books that I was reading, so I thought maybe I should start writing books that I would love to read. And it just so happened that I went to a middle school that was built in 1917 by the French administration in Vietnam at the time, so I [grew up] surrounded by original colonial architecture like French doors, symmetrical design, and all that. I was taught about that part of Vietnamese history very early on, and I kept feeling drawn back to that period.

When I first started sitting down to write, I did a lot more research into the period, and I came across two extremely wealthy and successful businessmen at the time, [a real estate tycoon and a rubber plantation entrepreneur]. And I started toying with the idea of them being childhood best friends, and what would happen if one of them was murdered. And the rest of the novel just sort of grew from that idea.

JB: The setting in 1920s Saigon is unusual for a murder mystery. Can you tell me more about what appealed to you about that time period?

JP: I feel like, especially with historical fiction, certain people will say that we should forget about what happened in the past, and focus on the future. But to me, there is nothing archaic about colonialization. Vietnam resisted and Vietnam won, but similar colonialism is still very much happening, given the genocide in Palestine right now. Other than my personal connection with the period, with the middle school that I attended, I wanted to offer a glimpse into the 1920s, because [despite] all the atrocities or injustices that were committed, there has never been any state recognition for those injustices. And it’s up to younger generations to keep telling those stories, not to hold grudges or anything like that, but to remind people of what happened. And just maybe we can all look back and think that we can — and we should — be better than that.

JB: I’m glad that you brought up Palestine, because I noticed some parallels in the novel with the atrocities and power dynamics we’re witnessing right now across the media. You’re working with an American publisher for this novel, and I wonder what takeaways you hope American audiences will glean about Vietnam from this book, particularly in terms of how they might contextualize current events.

JP: Even though Those Opulent Days is set in a completely different time period, in a completely different country, there are just so many parallels between what was happening in Vietnam and what is happening in Palestine right now. As a collective, if American readers were to read this book, I hope they can come to a conclusion that we’re all not free until we are all free. This can quite literally happen to any of us, so if we can, just extend a little more kindness, a little bit more sympathy. This topic is quite heavy, and every time I think about it, I feel so, so helpless.

JB: It is overwhelming, absolutely. And it’s easy to become desensitized to violence and oppression due to the deluge of horrific images we see daily online. I think the beautiful thing about fiction is that it makes us empathize with the subjects of the story and ideally grasp what’s happening to actual, real people in the world at a deeper level. I think your book does a beautiful job of immersing the reader in this way.

Let’s shift gears a little. Those Opulent Days opens with a prophecy that sets up the story but also haunts one of your four main characters, Duy. Why did you choose to include this narrative device?

JP: That has a lot to do with the culture, because we as Vietnamese people really do believe in the afterlife, prophecies, and a little bit of superstition. That guides our lives a lot. Obviously my parents are the same, so growing up, I was under a similar influence, and I find myself being drawn back to going to the fortune teller, asking about what the new year might be holding for us in terms of career, home life, that sort of thing. So it’s only fitting for a character to experience that same sort of mindset.

JB: You tell this story with multiple close points of views, ranging from the four central friend characters to their parents, servants, and romantic interests. What appealed to you about this rotating POV approach?

JP: When I first start writing any project, I have what I call a “draft zero” where there will be no editing involved. I just sit down and write out everything that comes to my mind. So the multiple points of view actually came very organically to me, and I just started writing under every single character’s point of view. And as I finished that draft zero and I went back to edit it, I realized that I actually enjoy that narrative choice, because one of the main themes of Those Opulent Days is the power imbalance between the working class and the elite. Without the perspectives from a variety of fleshed out, complex characters, the [imbalances] might not have been as nuanced, and the reading experience might not have been as immersive. And this is a murder mystery, [where] the multiple points of view really help with the mystery element. They give readers a sort of incentive to keep turning the page to see which characters’ actions and thoughts are red herrings, and which character has the most motivation to commit the crime.

JP: When I first start writing any project, I have what I call a “draft zero” where there will be no editing involved. I just sit down and write out everything that comes to my mind. So the multiple points of view actually came very organically to me, and I just started writing under every single character’s point of view. And as I finished that draft zero and I went back to edit it, I realized that I actually enjoy that narrative choice, because one of the main themes of Those Opulent Days is the power imbalance between the working class and the elite. Without the perspectives from a variety of fleshed out, complex characters, the [imbalances] might not have been as nuanced, and the reading experience might not have been as immersive. And this is a murder mystery, [where] the multiple points of view really help with the mystery element. They give readers a sort of incentive to keep turning the page to see which characters’ actions and thoughts are red herrings, and which character has the most motivation to commit the crime.

JB: This is a dark novel, touching on some difficult topics. One of the most moving aspects for me was its exploration of relationships between parents and children, specifically the extent to which parents will go for either love or control of their children.

JP: Similar to the prophecy. I feel like this is a cultural thing. In mainstream media, there is this narrative about “tiger moms” or Asian parents being extremely strict. And I want to offer an alternative perspective into that. When I was growing up, I was similar to the four friends in certain ways, like I would try to defy my parents’ teachings, I would think that they are being unreasonable, and things like that. But writing this book, especially in the POV of Madame Như, I tried to see things from her perspective and why she does what she does. Not that what she does is excusable, but deep down she is trying to do what she thinks is best for her son, given everything that’s happening at the time. Asian parents are not always controlling because they just like to be dominating, or they just like things a certain way. They have their own reasons — and whether or not we can understand those reasons is a different matter!

JB: Earlier you mentioned power imbalances. When colonialism enters a space, violence is inevitable, but I think corruption then becomes inevitable too, both because colonialism itself is a corrupt endeavor, and also because people become desperate to save themselves, their children, and their community from the violence. So corruption or corrupted loyalties become a means to survival. Can you share more about how you played with these layers of power and corruption in the novel?

JP: The murder mystery element aside, at its core Those Opulent Days is a [work of] historical fiction. So it’s important to me to convey the period authentically. Unfortunately, a lot of the things that I have described in the book are not fictional, like the fact that mothers had to sell their children to wealthier families to pay off debt, for example. During the French colonialization of Vietnam, we still had a royal family and even though they were emperor and empress, they only held symbolic power. They surrendered the real control to the French administration, and foreign people were placed on this sort of pedestal of “advanced civilization.”

I wanted that power imbalance to be reflected in the friend group as well. [Their friendship] is obviously the focal point of this novel, and even though they are best friends — they have seen each other at their worst, they have seen each other at their best, and experienced a lot of things together — there is still that underlying power imbalance, because at the end of the day, while things like wealth and knowledge help enhance power, they are just a means to an end, whereas true power [like the colonialists held] is an end in itself.

JB: Several threads in the novel focus on forbidden love between classes, but also between same-sex lovers. Why was it important to you to include both a queer love story and a romance between the privileged and the not?

JP: That is again a choice to highlight the fact that when bad things happen, they will affect everyone, not just any one individual in society. So if we don’t all get together to help dismantle those sorts of restrictive beliefs, no one has a chance of happiness. And that might be seen as a little bit too bleak, but my personal belief is that this is the reality that we’re living in.

JB: Yes, as you said earlier, none of us are free until we are all free, which is so true.

To wrap things up, let’s talk craft briefly. This is your debut novel, and I wonder if you could share a little bit about your writing process, be it research, plotting, revision, and so on.

JB: I’ve always been drawn to writing in general. Back in Vietnam, in middle school, I attended a specialized class in literature. So I’ve been writing my whole life, but obviously this is my first published work. My writing process, as I’ve mentioned before, starts with a draft zero, and it [entails] a lot of editing with my research process. For Those Opulent Days, it was actually a matter of recalling and fact-checking, and a lot of the details can be found in history textbooks that my mom still keeps. I just went back through all the pages and read up on all the information.

It’s also important to me to tell as unbiased a story as possible, so for a couple of months, I scoured the internet for articles written in both Vietnamese and English, because I wanted to ensure that the reality of the time isn’t in any way minimized or exaggerated [in the novel]. I came across pictures of workers at opium factories and rubber plantations, and their living and working conditions were so horrible that I just had to find a way to sneak it into the novel. I want for them to be remembered.

JB: You’re doing a great service in educating readers, because appalling working conditions still happen a lot globally. In America, where we live amid unfettered consumerism, we often don’t think twice about ordering that thing on Amazon that will be delivered tomorrow, or about how it’s made and where and by whom, and why it’s so cheap!

JP: Unfortunately, I feel like Australia is very much the same. And, even though I wrote this book, it’s not until very recently that I discovered how iPhones are made and how damaging [that process] is to the people of Congo. When every year a new phone is released, we — myself included, in the past — have to go and get a new phone. And for what, when the old ones are working perfectly fine?

JB: Yes, you can still use that old one and help save children from the cobalt mines.

Last question: what’s next for you?

JP: I’m currently working on my second novel, but it’s still fairly early stages. All I can say is that it will be speculative fiction, set in Vietnam again. My main goal [in my work] is to change readers’ immediate association when mentioning Vietnamese people or Vietnam in general. I don’t want for Vietnam or Vietnamese people to be associated with the infamous Vietnam War all the time, or with the refugee experience. They are extremely important to talk about, but I also want readers to see Vietnamese people like any other people: they can be extremely complex and layered and resilient. They don’t necessarily have to be associated with the worst thing that has happened to them. That is all that I can say [about the novel] at the moment, because I have not nailed down every single point. Draft zero, first, and everything else, second!

***