Doug Liman’s “Road House” remake spends most of its runtime keeping things as sunny and breezy as its Florida Keys setting. Elwood Dalton (Jake Gyllenhaal, replacing the original’s Patrick Swayze) is chief bouncer for the eponymous establishment, the kind of happy warrior who’ll drive a bunch of miscreants to the hospital after politely slapping them senseless in a parking lot. But near the film’s climax, Dalton’s character sidesteps in a darker, decidedly unpleasant direction—and places himself firmly in Gyllenhaal’s growing pantheon of warped noir characters.

During the scene in question, Dalton suffers a series of setbacks severe enough to seemingly crack his psyche in two. He responds by crushing an unarmed dude’s throat, then desecrating that dude’s corpse by shooting it full of bullets, then using the corpse as leverage against a corrupt cop. Things are getting deranged, and yet Dalton maintains his aw-shucks attitude throughout, his eyes gleaming with brutal good cheer; for a few minutes, he’s more of a serial killer than a fighting monk. And then the film, as if startled by its own twist, abruptly shifts back into traditional action-movie mode, with Dalton reverting to clichéd tasks such as Saving the Girl and Beating Up the Bad Guy.

That scene alone places “Road House” in the same category as “Nightcrawler,” “Ambulance,” and other neo-noir films in which Gyllenhaal plays some variation of a twitchy psycho, subverting his movie-star image. He’s the latest in a long line of extremely photogenic actors who use noir to toy with the dichotomy between a beatific exterior and a horrifying interior life, and he’s good at it.

“Nightcrawler” (2014) is perhaps the most famous iteration of these noir-centric roles. Gyllenhaal plays Lou Bloom, an L.A.-based news stringer who cruises the night for accidents and murders to film, then sells the footage to local news stations. Lou manipulates and lies his way to success, with an utter willingness to set up situations that result in death. Gyllenhaal lost extreme weight for the role, giving him the hungry countenance of a vulture, and the character has no redeeming features unless you count murderous ambition as a positive.

The “Nightcrawler” role wasn’t an outlier among his morally depraved roles. Take “Ambulance” (2022), which is every inch a Michael Bay joint: even before Gyllenhaal’s Daniel Sharp and his adopted brother Will (played by Yahya Abdul-Mateen II, who panics nicely as the action accelerates) rob a bank and hijack the titular vehicle as part of their getaway, the pace is frenetic, the camera swooping like a meth-addled crow through the action, every character shot at epic angles. In contrast to the funny, generally upstanding protagonists of other Bay films, Gyllenhaal is a genuinely bad man, the type who can disarm with a kind word but jam a rifle in an EMT’s face a few minutes later.

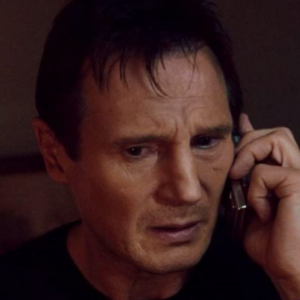

As the movie’s crises accelerate, Gyllenhaal’s glibness tips into pure sociopathy; hints of his later performance in “Road House,” along with a hefty dose of Cagney’s climactic screaming in “White Heat”:

Not all of his characters are warped in quite the same way, even if they’re barely repressing something dark. In “Prisoners,” he plays a detective who begins to snap under the pressure of solving a kidnapping case, alternating between explosive interrogations and shuddery implosions, as in the latter scene:

If we imagine the intensity of Gyllenhaal’s noir performances as a scale, with “Nightcrawler” pegging the needle at a 10 (Maximum Dark) and his cop in “Prisoners” jittering at around a 5 (Typical Twisted Noir Anti-Hero), then his role in David Fincher’s serial-killer flick “Zodiac” probably rates a 1 or 2. Amidst the sprawling investigation into Northern California’s most famous murderer, Gyllenhaal’s Robert Graysmith—a cartoonist who finds himself hunting the Zodiac in parallel with the police and reporters—largely serves as the audience’s avatar. In this instance, the twitchy fireworks largely come from Robert Downey Jr. as Paul Avery:

Gyllenhaal isn’t the first actor to use noir to show his range, along with a dark side; that tradition goes back to the genre’s golden age, where every heartthrob from Kirk Douglas to Fred MacMurray crawled the underside in a few titles. (That’s in addition to the women who played femmes fatales, a role that can veer between misogynistic and empowering, sometimes in the same movie.) The difference is, at least in a contemporary context, most stars seem to keep these journeys limited. Witness Tom Cruise in “Collateral,” doing an excellent job of playing a sociopathic hitman teetering on nervous collapse—and, having shown the world he could do it, opted to never portray that kind of character again.

But Gyllenhaal can’t seem to help himself. Even in a movie like “Road House,” where another star might have demanded a script that made them unambiguously heroic, he’s inclined to infuse at least some moral ambiguity into it, if not psychopathy. In some ways, he’s closer to Michael Shannon than Tom Cruise—and his willingness to explore those depths perhaps makes him noir films’ unsung MVP.