As often as James Bond engaged in casual sex, you know he’s got some offspring around the world.

But we’re here today to talk about another kind of spawn of Bond: the movies, TV shows and comic books that hoped to cash in on the mania for the superspy.

And while Bond imitators have popped up for sixty years—“No Time to Die,” the 25th in the official film series released today, will no doubt be felt in modern-day pop culture—we’re looking at the impact of Ian Fleming’s 007 in the 1960s and 1970s.

It was a time when you almost couldn’t dodge Bond-inspired movies, TV shows and comic books. You couldn’t turn around without stumbling over a suave agent with a license to kill, a femme fatale with a provocative and corny name or a globe-girdling secret organization. With a corny name.

Bond’s history is well known. The character debuted in author Ian Fleming’s first Bond book, “Casino Royale,” published in 1953. Fleming published a book a year until 1966, when “Octopussy” and “The Living Daylights” were published. Presidential hopeful John F. Kennedy told Fleming how much he enjoyed the books. But when Kennedy mentioned in a 1961 White House interview that he was an avid reader of the series, their popularity—already great in the United Kingdom—jumped in the United States.

So while the books were well-established before the first film adaptation, “Dr. No,” came out in 1962, the movie versions heightened awareness and spawned a legion of imitators.

Strangely enough, what might be the best-known of the movie imitators owed a debt to Fleming, but Donald Hamilton’s books about American spy Matt Helm began in 1960, two years before the first Bond movie.

There’s no question that the four Matt Helm movies owe a great debt to Bond.

Dean takes a shot. Several, actually.

Donald Hamilton wrote 27 (!) books about Helm, beginning in 1960 and finishing up in 1993. Unlike Bond, Helm is an American agent. He served in World War II so would, if he were left to the passage of time, age out of his action-oriented role. So would Bond, of course. But both men were quickly made ageless.

I can’t testify as to how good or bad Hamilton’s books are. But I can tell you that the movie versions are not James Bond quality. Even as varying in quality as the Bond films can be.

Watching the first of the four Helm movies, “The Silencers,” from 1966—after five Sean Connery bond films had been released—you’re struck by how dated it seems. Sure, there are some dated qualities to the Bond films, especially the attitudes toward women and the largely nameless and faceless people of color who were bystanders in the Bond plots. But the Helm films, starring Dean Martin, seem as if they would have felt dated before they opened in movie theaters.

Advertised as something of a spoof, “The Silencers” featured Martin, known for his easy-going, boozy persona, as an American agent who prefers his day job as a globe-trotting photographer. Considering his regular encounters with models and liquor, really, Martin is ideally cast.

With character names like Lovey Kravezit—a woman bedded by Helm; could you tell from the moniker?— and the threat of spy organization The Big O, there’s no doubt there’s supposed to be humor here.

Not funny is the Asian criminal mastermind Tung-Tze, played by … Caucasian actor Victor Buono.

Watching “The Silencers” now feels like it’s the proof-of-concept film for every Bond spoof that followed for decades, including the more “out there” entries in the Pink Panther movies or the Austin Powers films.

Three films starring Martin as Helm followed “The Silencers.” These days, the final film, 1968’s “The Wrecking Crew,” is remembered mostly for references to it in Quentin Tarantino’s 2019 film “Once Upon a Time in Hollywood,” which included characters drawn from two real-life figures from “The Wrecking Crew”—Bruce Lee, who did some fight choreography on the Martin film, and Sharon Tate, who played a character in the Helm movie.

There’s nobody whose songs I’d rather hear as ambiance in an Italian restaurant, but Martin’s time as a Bond imitator was lackluster.

Bond’s greatest competitor

As far as Bond parodies and imitators go, the Flint movies were better than the Helm movies. Tough-guy actor James Coburn played another American spy, Derek Flint, in “Our Man Flint,” from 1966, and “In Like Flint,” from 1967.

It helps, no doubt, that Coburn has such a great screen presence, even in movies that are at least partially full of hooey. Like the Flint movies.

“Our Man Flint” has a plot that was or surely should have been stolen for a Pink Panther or Austin Powers movie: Three scientists learn how to control the weather. Naturally, blackmail ensues. (Cue Dr. Evil voice: “One MILLION dollars …”)

Flint is a former agent of ZOWIE (Zonal Organization World Intelligence Espionage, a name that sounds like the product of really strange refrigerator poetry magnets) who is called in by his former boss, Cramden, played by Lee J. Cobb as a man who seriously hates his most effective agent. I don’t mean that Cramden is scoffing or mocking of Flint like M was of Bond. Cramden appears to consider the option of letting the bad guys ravage the globe with weather rather than call upon Flint.

As Flint, Coburn is just so damn cool. He’s lackadaisical as all hell and an expert in everything. I mean, everything. He knows obscure ingredients for dishes, he can fight, he can romance the ladies and he can restart a man’s heart by forming a short human chain with, on one end, Cramden’s finger in a light fixture. Don’t try this at home, kids.

But he doesn’t want to come back to work.

Cramden: “Flint, the world’s in trouble!”

Flint: “It usually is, but it manages to extricate itself without my help.”

Flint keeps house with four women who wait on him hand and foot and become plot points, although very of-their-time plot points.

The movie hits a lot of Bond notes: A brief encounter with Agent 0008. An attempted assassination with a dart-shooting harpist. A Walther PPK and briefcase of weapons that Flint turns down in favor of a cigarette lighter with 83 functions.

There’s even an enemy agent named Hans Gruber. Shades of “Die Hard!”

Bonus: If you’re watching “Our Man Flint,” be ready for the ringtone that plays whenever the president calls Cramden. It’s insane, it was used in a few other movies and TV shows and I want it as my ringtone.

Adventures on the small screen

TV, which was for decades derided for imitating movies, saw an explosion of Bond imitators and parodies in the 1960s and 1970s.

There was “Mission: Impossible,” the 1966 series that addressed the implausibility of Bond or Flint being experts in everything by assembling a team of agents, each with a skill, whether in electronics, creating disguises or the ability to fool the Balkan dictator of the week. And there’s “The Avengers,” the British spy series that reached its peak when it teamed Steed (Patrick Macnee) and Emma Peel (Diana Peel, the object of millions of crushes for decades). The series was offbeat enough that it didn’t feel like a reaction to Bond, and it debuted in 1961, before Bond movie mania took hold with “Dr. No.”

A TV outing aimed at kids was “Lancelot Link, Secret Chimp” and, well, the title speaks for itself. Funnier and more adult was “Get Smart,” the spy series takeoff created by Mel Brooks and Buck Henry. It debuted in 1965 and lampooned every spy story staple and made sure they were soon considered spy movie cliches. One example is the good-guy espionage organization, CONTROL, and the bad-guy group, KAOS.

My beloved “The Adventures of Jonny Quest,” an animated series that debuted in prime time in 1964—four days before “The Man from U.N.C.L.E.”—and featuring one of the most propulsive opening credits themes ever, did Bond-style spy adventure better than any TV show and most of the movies. “Jonny Quest” likewise split the Bond persona into Dr. Quest, the genius, and his bodyguard Roger “Race” Bannon, the agent assigned to protect the doctor and his sons, Jonny and Hadji.

Bannon could hold his own not only in the rough-and-tumble world of enemy agents and fiendish villains but was known for his past romance with the equally tough and mysterious Jade. It was a surprisingly adult relationship for the time and medium.

The best-known TV treatment of the Bond-created genre—at least in live action—was “The Man from U.N.C.L.E.” and its spin-off series, “The Girl from U.N.C.L.E.”

The original series debuted in the fall of 1964 and, over the course of four seasons and 105 episodes, maybe did more to popularize the spy story—for kids at least—than the Bond films.

The status of the series was fitting considering their pedigree: Bond author Fleming helped draft the concept and some of the characters.

Robert Vaughn starred as Napoleon Solo, an American agent, and David McCallum co-starred as Illya Kuryakin, a Russian agent. They countered the hostile moves of THRUSH. If the series was intended as a vehicle for Vaughn, the producers didn’t take into account how popular the Russian—with his Beatles-style haircut—would become.

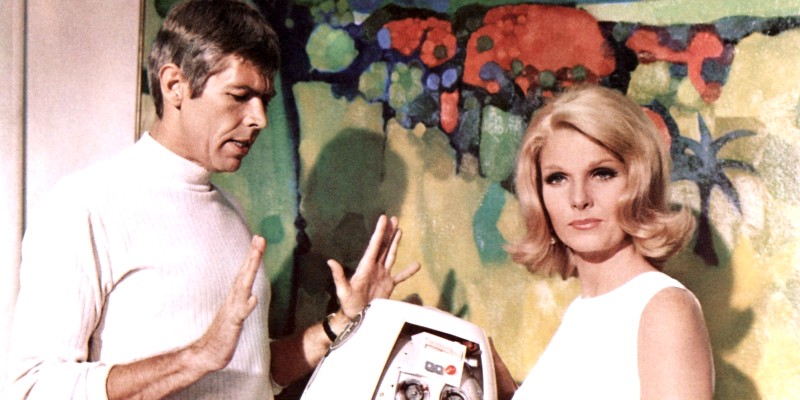

The female-agent-centric spinoff, featuring Stefanie Powers as agent April Dancer, debuted in 1966 and lasted a season. It shared the spy universe of the original series and some of the characters, notably the “U.N.C.L.E.” leader, Alexander Waverly, played by Leo G. Carroll.

When I was a kid, I had a “Man from U.N.C.L.E.” toy set that included a gun—of course—and other Bondian accessories. As popular as the “U.N.C.L.E.” series were, the merchandising, including toys, books and comic books, almost overshadowed the series. My friends and I played spy non-stop, although I never wanted to be a THRUSH agent. I mean, who did?

I’m here to declare, though, that the best ersatz Bond action came from the pages of comics.

The coolest spy of them all

Nick Fury started out as a battle-hardened World War II soldier in Marvel comics. The original “Sgt. Fury and His Howling Commandos” comics, created in 1963 by Jack Kirby and Stan Lee, were among a wave of World War II-based entertainment in various mediums for a decade.

If you were a kid in the 1960s, like I was, World War II was a recent touchstone in history. Our fathers—my father—served in the military during World War II and our families got their start in the shadow of the war. So Fury, a gruff, go-for-broke soldier and brawler, became one of the best-known fictional characters based in the war years. He helped make the war that our fathers fought seem recent and gritty and real.

But it was the big change that Lee and Kirby executed for Fury that made him a relevant figure in the 1960s and until this day.

Although the World War II-set comic series ran from 1963 to 1981, Kirby and Lee created “Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D.” in 1965, and the comic was clearly intended to capitalize on James Bond.

Fury, by now a colonel, was re-introduced as an eyepatch-wearing agent for the covert U.S. agency S.H.I.E.L.D. The series was jam-packed with imagination and innovation, like a lot of the Marvel comics universe.

Fury operated in a world that included floating helicarriers, flying cars, Life Model Decoys—perfect but expendable robot copies of anyone, particularly Fury—and out-of-this-world weaponry. Fury’s hardware wasn’t merchandised like Napoleon Solo’s was, but all of us knew who would win in a firefight.

For that matter, how could James Bond possibly defeat Nick Fury? Let’s see, Bond has an Aston Martin with a built-in machine gun. Fury has all the guns. All of them, and they were as big and weird as Kirby—and later artist Jim Steranko—could make them. I mean: Helicarriers.

Steranko’s art, particularly in the Fury books of the mid-1960s, was phantasmagorical. The comics covers alone were mind-blowing, with Fury in black leather posing against psychedelic backgrounds and fighting intimidating bad guys from A.I.M. and Hydra.

Of course, most people now know Fury as Samuel L. Jackson, the actor who served as the physical model for a rebooted Fury in the comics. For a while, at least, the two versions of Fury—old, white World War II veteran and younger, Black spymaster—co-existed in the comics. The trappings of S.H.I.E.L.D. from the comics came with the rebooted Fury to the big-screen Marvel Cinematic University, starting with Jackson’s Fury surprising Tony Stark at the end of the first “Iron Man” in 2008.

So, twice the Nick Furys, twice the cool.

You could make the argument that Fury, with appearances in a string of Marvel movies and TV shows, is bigger than Bond and will have more longevity than Bond.

Maybe I wouldn’t go that far but ask your average 12-year-old who is they’d rather play, Fury or Bond.

Go ahead. I’ll wait.