“America was never innocent. We popped our cherry on the boat over and looked back with no regrets. You can’t ascribe our fall from grace to any single event or set of circumstances You can’t lose what you lacked at conception…It’s time to demythologize an era and build a new myth from the gutter to the stars. It’s time to embrace bad men and the price they paid to secretly define their time.”

Article continues after advertisement

So reads the prologue to James Ellroy’s 1995 historical novel-cum-conspiracy thriller, American Tabloid. It’s an exordium that adequately encapsulates Ellroy’s entire fictional output, up to and including his newest book, This Storm, released today. The novel chronicles the operations and machinations of various corrupt police officers and underworld figures traversing war-crazed Los Angeles in weeks following Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor.

Those lines could just as well be describing the Deadwood, HBO’s ensemble western/crime saga created by legendary TV scribe David Milch. Set in the early days of the real-life Black Hills mining camp, the show follows the rogue’s gallery of killers, thieves, con men, prostitutes, prospectors and fortune seekers that populated the volatile no-man’s-land during one of the most violent periods in U.S. history. Last week, HBO aired Deadwood: The Movie, the highly-anticipated conclusion to the show.

Both projects have been a long-time coming: it’s been 5 years since the publication of Perfidia, Ellroy’s bloody and rococo return to his stomping grounds of Los Angeles, and 13 years since Deadwood originally went off. While half a decade isn’t an unreasonable wait time for a new Ellroy tome (his latest clocks in at 608 pages), Deadwood fans had all but given up hope they’d ever see the conclusory film promised them by HBO following its abrupt cancelation in 2006. That changed in 2017 when, amidst a flurry of television series reboots and resurrections, the network announced they were finally moving forward production on Deadwood: The Movie, with almost the entire original cast reassembled and Milch at the helm as writer and producer.

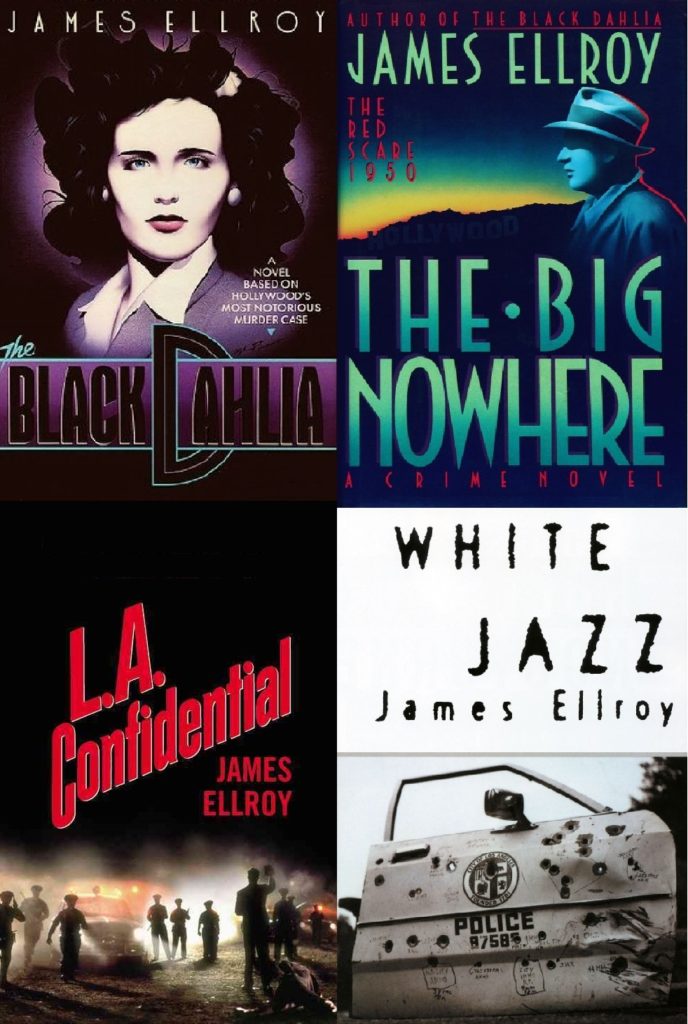

Meanwhile, and perhaps just as improbably given the scope of the project, Ellroy finds himself halfway through his latest multi-novel cycle which, once completed, will bind all of his preceding interconnected fiction—including the 1982 novel Clandestine, the original L.A. Quartet (The Black Dahlia, The Big Nowhere, L.A. Confidential, White Jazz), and the Underworld U.S.A. Trilogy (American Tabloid, The Cold Six Thousand, Blood’s A Rover)—into an astonishing thirty-year secret history of American violence, vice, and power.

It feels significant that both projects should come out at the same time. Despite their disparate upbringings and career paths—Milch, 74, is an alumnus of Yale University, where he served as protégé to the esteemed poet and novelist Robert Penn Warren and was a fraternity brother of George W. Bush; Ellroy, 71, a native son of Los Angeles, flunked out of high-school and got booted from the Marines before embarking on a career as a writer while earning a living as a golf caddy—it’s hard to think of two more kindred artistic spirits currently working.

Much of what they have in common stems from their biographies, which are littered with protracted criminal misadventure and personal tragedy:

Ellroy has spoken and written at length about the 1958 unsolved rape and murder of his mother, Geneva Hilliker Ellroy, most notably in his 1996 memoir, My Dark Places; Milch also experienced a sudden and violent parental death, though much later in life. During a Forum held at MIT in 2006, he told of how his father, long suffering from mental deterioration and addiction, killed himself in front of his wife and son (David’s mother and brother) after accusing them of having sexual relations. Aware that his other son, David, was at a pitch meeting with the National Endowment for the Arts at the time, his last words were, “Don’t tell David until his pitch is done.”

Both men spent a good part of their lives battling addiction—Milch to booze, heroin, and gambling; Ellroy to booze, pills, and sex compulsion. Both also dabbled in crime—Milch with drugs and guns, Ellroy with petty theft and trespassing—and both did a little time—Ellroy in L.A. county lockup, Milch in a Mexican jail. Both men eventually got clean and found massive success in their chosen fields, but have been met with a variety of relapses, setbacks, and unfortunate turns of fate over the years.

The demons that have pursued them in life—addiction, compulsion, abuse, familial trauma (themes of incest carry a particularly heavy weight throughout their work), violent death, the long and painful process recovery—also haunt their art. Given the extremity of these subjects and obsessions, it only makes sense they’d find the greatest opportunity for expression within the genre of crime, although it is somewhat surprising, given their pasts, that they’d make their bones writing about cops (Ellroy throughout all of his novels, Milch as a writer and producer on shows like Hillstreet Blues and NYPD Blue).

But as Milch described it during his MIT forum, his experiences on the wrong side of the thin blue line allowed him to present “a more accurate representation of at least one aspect of policing.” Ellroy was clearly well-acquainted with that same aspect, as the cops in his stories can easily be swapped out for those in Milch’s: between their boozing, self-flagellation, and shambolic demeanor, there’s very little daylight between L.A. Confidential’s “Trashcan” Jack Vincennes and NYPD Blues’s Andy Sipowicz. Likewise, when a character in Deadwood describes the show’s morally upright, but homicidally-repressed Sheriff Bullock as either “a cunt-driven near maniac or a stalwart, driven by principle,” they may as well be referring Confidential’s Officer Bud White.

Milch and Ellroy’s writing styles are similarly sympatico, even as they reflect their discrepancy in education—Milch has his characters speak in flowing verse strewn with all the poetic allusion, philosophical digression, and linguistic puns you’d expect from someone who taught English literature at the Ivy League; while Ellroy adopted the telegraphic and staccato style found in the scandal rags and true detective magazines of his youth.

Their styles intersect over their shared love and deep knowledge of, as Ellroy describes it, “slang…hipster patois, racial invective, alliteration, argot of all kinds.” If a Mount Rushmore were erected in honor the greatest poets of American profanity, it would undoubtedly feature both men’s likeness.

Their adherence to extreme language, especially when it comes to the unsentimental deployment of the above-mentioned racial invective, puts them decidedly out-of-step with modern artistic mores. Per Ellroy, via the Paris Review: “Critics want racism, and secondarily homophobia, to be portrayed as a defining characteristic, rather than a casual attribute. Racist language uttered by sympathetic characters confuses hidebound liberals. Who gives a shit.”

In staying true to their gutter-mouthed muse and refusing to do any moral handholding, Milch and Ellroy have given audiences a more honest and convincing portrait of America—America as it is today, America as it always has been—than just about any other writers in their respective mediums.

They don’t dance around when it comes to their premise: America itself is a crime. All of it—the country’s foundation, its westward expansion, its global ascendance—is the result of avarice and butchery, of “bad men shaping events with the virulence of their greed and hatred, riding full-blast shotgun into history.”

Neither writer is interested in excoriating or subverting the prevailing myth of American exceptionalism—the “lie agreed upon,” to borrow a quote from Napoleon and the title of an episodic arc of Deadwood—for base political reasons. Their concerns lie in the realm of the spiritual.

As Ellroy explained in an interview with The AV Club, “For all my dark curiosities and profane shtick, I’m a moral guy, and the books are moral, and I think I’m a moralist. I’ve said this before, so if you see this quote on the Internet, don’t be surprised: Morality in literature is largely the expositing of moral acts and their consequences, the karmic price of the perpetrators of the immoral acts, for having committed them. In that sense, I think [my] books are very moral.”

Still, and despite the brutality of that karmic price within his stories (maiming, murder, madness—the works), Ellroy is no Old Testament disciplinarian. He is not content to simply punish his characters, but rather guides them towards a reckoning leading ultimately to redemption. For Ellroy, the catalyst for redemption is love. He likes to sum up his novels as “bad men in love with strong women.” Accurate, although he sells short his abilities at writing fraternal love, which is just as powerful a motivator in his stories. Regardless, adherence to love overrides his characters self-interest and even their survival instinct, causing them to change allegiances, betray deeply-held ideologies and prejudices, and commit acts of mortal sacrifice.

The same is true of the characters in Deadwood. Is there any greater redemptive arc in all of television than Al Swearengen’s? The criminal and political mastermind begins the series (unsuccessfully) ordering the killing of a small child and plotting to swindle a recently widowed woman (who he’s responsible for widowing, naturally) out of her fortune. Come the end of the third season, Swearengen leaps over the rail of his balcony where he’d plotted those evil acts and throws himself in front of gunfire aimed at that same woman and child. His redemption is also inspired by love—love for a former prostitute he used to employ; love for his friends and allies; love for the town he helped build through bloodshed and subterfuge. If, by the last episode, he hasn’t changed his violent or rapacious ways (and he hasn’t), he has directed the greater measure of his efforts to helping those around him—even if it means sacrificing his own life.

In Milch and Ellroy’s fictional universes, there’s almost no one inherently irredeemable…which isn’t to say that everyone gets redeemed. It’s no coincidence that the archvillains within their stories are all renderings of real-life powerbrokers with a verified history of atrocity to their name. George Hearst, J. Edgar Hoover, Howard Hughes—these men managed to consolidate great wealth and ultimate power and hold onto it, but only by renouncing any meaningful connection to their fellow man. Though they all survive into old age, Ellroy and Milch depict them as dead in their souls, as well as utterly, irrevocably alone.

***

Ellroy is often dubbed a writer of noir, which is understandable given the plots and settings of his stories, but inaccurate: noir is all about doomed people striving to change their circumstance, only to be undone by some inborn fatal flaw—greed, lust, hubris (or a combination all three).

As Ellroy himself puts it: “The great theme of noir is, you’re fucked.” His characters may well end up fucked in the end (they certainly end up dead a good amount of the time), but just as often, they manage to change their circumstance, successfully moving through the inferno and receiving some measure of personal grace on their way out.

Deadwood is often compared to the dark dramas it aired alongside or preceded—The Sopranos, The Wire, Breaking Bad, Mad Men, but while it shares their proclivity for anti-heroes and noir trappings, its thematic arc bends in the opposite direction. Those series were about people and systems in a state of moral decline who find themselves ground-up in the remorseless gears of capitalism and helpless to stop it. Deadwood, on the other hand, depicts the blossoming of social order from a state of chaos. And while it offers a similar critique of capitalism, it nonetheless suggests that the collective good can take root even within the most violent locus of Darwinian self-interest.

The work of David Milch and James Ellroy present an unremittingly brutal vision of America built on a framework of atrocity and upheld by the bloody acts of unscrupulous men. It is a dark and terrible vision, and it rings entirely true. It is also, ultimately, a hopeful vision, offering a just-as-convincing argument that redemption is ever in our reach, and that by saving one another, we can save ourselves.

I can think of no more vital point-of-view for this current moment in history.