“A literature that cannot be vulgarized is no literature at all, and will not last.”

Frank O’Connor laid it out. He wrote the words at the cusp of the 20th century. Said words prophesied the hard-boiled novel. Hard-boiled scorched its artistic debut on February 1, 1929.

Dashiell Hammett’s first novel, Red Harvest, hit bookstores. Hammett’s narrator, the Continental Op, goes in strong:

“I first heard Personville called Poisonville by a red-haired mucker named Hickey Dewey in the Big Ship in Butte.”

Hammett slammed the tonal chord for the entire hard-boiled canon. The vulgarization of American Literature tapped Art. Hammett was our first great hard-boiled artist. He vulgarized the American idiom and reinvented our native slang. It’s the language of disparagement and one-upsmanship. Hammett revised the myth of the frontier male and recast it as urban estrangement.

“The core of Hammett’s art is the masculine figure in American society. He is primarily a job-holder. He goes at his job with a bloodthirsty determination that proceeds from an unwillingness to go beyond it.”

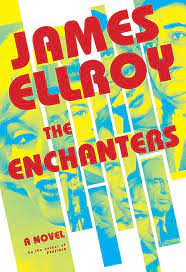

David T. Bazelon laid it out. He adroitly summarized Hammett’s career and my career before I was born. Hammett and I comprise the alpha and the omega of the American hard-boiled novel. Ninety-four years, six months, eleven days. That’s the distance between the publication of Red Harvest and the pub date of my new novel, The Enchanters.

X X X X X

It’s the sizzling summer of 1962. I’m 14 and suffer from a kid case of male malaise. I bop around L.A. and emit bad vibes. I sniff cultural trends. They vex me. Mattress Jack Kennedy gores my goat. He’s out to remake the world in my non-image and scotch my shot to be prez and find a girlfriend. Three-hour Italian flicks glorify dislocation. I’m a Lutheran choirboy torched by deep belief and unsavory imagination.

L.A. ’62 gored my goat. Glass skyscrapers disrupted my perfect skyline. Cars went aerodynamically svelte. Book typeface went to lower-case letters. Furniture went space age. The culture went batshit crazy and stirred my wrath.

It’s modernism, redux. Talk about dislocation. 1920s Berlin dropped on my head.

I had an afternoon paper route. I delivered the Marilyn Monroe dope-OD headlines. Subscribers stood on their porches and snatched the papers out my hands. A little gear in my head went click-click.

I read the L.A. Herald cover to cover. The daily news vexed me. I was prone to vexation and jejune rage. I was set to start high school in September. It scared me. Everything scared me and enraged me. I lived to read hard-boiled crime novels. I recast myself as the frontier male up against urban estrangement. I talked to women who weren’t in the room with me. That habit persists to this day. I was learning to shut the world out and live within myself. I was that way in ’62. I’m that way today. The summer of ’62 was an all-time horrorshow-blast. I knew I’d write a book about it one day.

X X X X X

I lived with my loser dad and an unhousebroken hound dog. Our pad clipped the south edge of Hollyweird. South Hollyweird adjoined swank Hancock Park. I walked my hound dog late at night and peeped windows. The Wilshire branch library stood close. I scored my crime novels and true-crime books there. I scored my adults-only fare at Crown Liquor.

Crown catered to a juicehead-divorced dad clientele. Paramount wage slaves glommed their jungle juice and TV dinners there. Amphetamine-pushing male prostitutes lived above the store. They fueled my epic reading binges for a dizzy decade-plus. Crown featured two paperback racks. Rack #1 veered upscale. Irving Wallace, Jackie Susann, Harold Robbins. They were pop-fiction class acts by Crown Liquor standards. Rack #2 smut-scorched you. The Stewardesses, The Call Girls, The Nymphomaniacs, The Housewives, The Gynecologists, The World Rapers.

I gorged off both racks. I read Harold Robbins’ masterpiece, The Carpetbaggers. Robbins merged pop-fiction breadth and scope with a hard-boiled style. It was a classic roman-à-clef job.

I transposed myself to the text. I built airplanes with Howard Hughes clone Jonas Cord. I poured the pork to Jean Harlow clone Rina Marlowe. I trekked with a half-paleface/half-Indian kid named Nevada Smith. We hunted down the psycho cowpokes who offed his parents. I designed an aerodynamic brassiere like the one Howard Hughes whipped up for Jane Russell. I lived through the history of the epoch before my birth. The prose was clean and raw. I read The Carpetbaggers for kicks and grins. Robbins wrote the book for my dipshit-kid eyes only. He shot me a backstage pass to the hard-living/hard-loving/adults

Robbins peaked with The Carpetbaggers. He tanked with The Adventurers and The Inheritors. I dumped him off my must-read list. I went on a detective-novel tear. The seditious ‘60s sizzled as I peeped prep-school girls and read American Hard-Boiled Fiction. I got kicked out of high school and the army. My old man died. I returned to L.A. I boosted steaks and books and got in kid scuffles. I got popped for shoplifting, and spent two nights at Georgia Street juvie. I was 17 and too old and malodorous to adopt. The court declared me an emancipated juvenile. I got a job shelving books at the Wilshire branch library.

I shelved faaaast. I minutely examined the books I pawed through. I scoped dust-jacket art and read flap copy. I was gobsmacked by the dust jacket on Ross Macdonald’s The Zebra-Striped Hearse.

A white background offset by a hot pink, gray, and black typeface. It was modernist and très true to the time and place: L.A./1962. Plus — there’s the sinfully sinister and symbolic vehicle itself.

It’s not quite a morgue van. It’s more like a surf wagon. It connotes Pali High boys in plaid Pendletons and Levi cords, and Hollywood High girls in crocheted bikinis.

The jacket seduced me. I read the book. It knocked me flat. I’ve read far better books since. I’ve written far better books. I read Hearse in the mid-fall of 1965. It was published on 11/15/62. It took me back to my very own haunted summer. It gave me the already moribund gestalt of three years back, as the ‘60s stumbled and pratfalled ahead. It gave me bombed-out expatriates, the depraved rich, the corrupting legacy of unearned money. It gave me minute domestic grief as the grounds for homicide. It threw my smogbound home town back at me and exhorted me to top this!!!!! It gave me 278 pages of breathless plot and ceaseless detectives’ insight. I fell under the spell of a big and klutzy rich girl named Harriet Blackwell. I loved her in the mid-fall of 1965 — and I’ve loved her that much more on a dozen successive rereads.

It was the most exultant reading experience of my young life. Ross Macdonald dropped a match and sent me to Cinder City. I discovered the beauty of tragedy. I’m ever the Lutheran choirboy. I caught glimmers of redemption in murderous squalor.

X X X X X

COVID was good to me. I hide and shut the world out in prosaic times. Exceptional times do not alter my routine. Young to old, then to now. I ignore the contemporaneous world and live in the historical eras I depict in my books. I’ve been interviewed six trillion times. I’ve been the subject of seven documentary films. Interviewers harp on my mother’s 1958 murder and cite childhood trauma as the fount of my gifts. I’ve played along. It jukes book sales. Disingenuousness is a sin. I’m writing this essay in the spirit of atonement. My ongoing biography should be revised to reflect this:

I’m just a numbnuts kid who loves to read. The books I read taught me to write. I love American Hard-Boiled Fiction. I rarely stray from that oft-maligned canon. The Enchanters hits bookstores September 12. It’s far and away my best book. It’s an ode to Red Harvest, The Carpetbaggers, The Stewardesses, The Call Girls, The Nymphomaniacs, and The Zebra-Striped Hearse. It’s a monument to Crown Liquor.

The Enchanters recreates hellhound summer ’62. It gives form to all my buried lusts and fears. It features my late pal Freddy Otash, the overhyped Marilyn Monroe, the groovy L.A. cops Daryl Gates and Whiskey Bill Parker, the redoubtable Robert F. Kennedy. The Enchanters is modernist. The fractured love scenes exceed the fractured love scenes in Fellini’s La Dolce Vita and Antonioni’s L’Avventura. The book reads modernist and looks modernist. I want readers to grok my books for their sheer design sense. The look of this book immolated my brain before any and all textual considerations.

“Opportunity is love.” It’s my get-through-life maxim. Freddy Otash voices it in The Enchanters. I’m paying off a debt to my creative antecedents. They’re long gone now. The Enchanters was calculatedly conceived. I’m out to give Joe and Jane Reader the jazzy book thrills of my youth. Joe and Jane, I wrote my best book for you.

James Ellroy

Denver, Colorado, 5/18/23

Author image by Marion Ettlinger