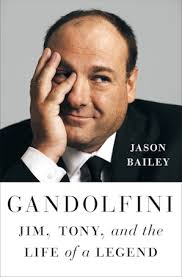

The New York tabloids covered his death with all the respect and nuance with which they’d covered his life—which is to say, none. TONY SOPRANO DEAD , read the front-page headline of the New York Post, with an interior article hed of LAST ACT FOR TONY SOPRANO, while the New York Daily News went with the simpler TONY’S DEAD on the cover and ‘MOB’ STAR’S SHOCK END: TOP ‘SOPRANO’ FELLED BY HEART ATTACK ON ITALY TRIP on page 2. It was one last indignity from the papers that had treated him so balefully, especially in those early years of the show, the Beatlemania years, when The Sopranos was the new sensation, when every Sunday night airing was an event, and when his every move (every night out, every fan interaction, every business deal, and then the divorce, dear God, the divorce) had been chronicled, analyzed, and sensationalized by those second-rate rags.

And now here they were, sticking it to him again. He hadn’t been Tony Soprano for six years—six years almost to the day, the tenth day of June 2007, the cut to black heard ’round the world—but that’s what they were still calling him, alongside cover photos of him in his Tony duds, his clean-shaven face a menacing scowl. Yet that wasn’t who he was, not then, and certainly not now. “You can’t go on saying we lost Tony Soprano,” his co-star and friend Vinny Pastore pointed out, not long after. “We didn’t lose Tony Soprano. We lost James Gandolfini.”

But over the course of eighty-six hours of television spread across nine years, people felt like they knew Tony Soprano, the anxiety-prone mob boss and family man at the center of HBO’s The Sopranos, a series that one can say, without hesitation, changed American popular culture. This deeply complicated, frequently monstrous, yet oddly sympathetic antihero was one of the great characters in television history, and as most of the show’s viewers had no previous recognition or understanding of James Gandolfini, the actor and the character fused into one.

For a time, that was how he liked it. When the show took off, he decided that press overexposure of James Gandolfini would make the audience less likely to believe him as Tony Soprano; he wanted them to focus on the character, not the actor. But after a time, it became clear that he just didn’t like sitting for interviews and profiles. “I’m not trying to be difficult,” he said in a rare one, with the Newark Star-Ledger’s Matt Zoller Seitz. “It’s not that I’m afraid to reveal personal stuff. . . . It’s just that I really, genuinely don’t see why people would find that sort of thing so interesting.”

So if James Gandolfini wasn’t Tony Soprano, then . . . who was he?

___________________________________

___________________________________

It’s the most basic question a biographer must ask, and one that Gandolfini, in his lifetime (and, somehow, after it), didn’t make easy to answer. His all-out resistance to interviews softened somewhat in the post-Sopranos years, in which he realized that the anti-Tony roles he desired were mostly found in meaningful but low-budget indie films, so his personal press availabilities helped to get the work seen. But he still gave precious few in-depth, long-form interviews—an Esquire profile here, a sit-down for Inside the Actors Studio there—and the people he worked with kept a code of silence around their patriarch that rivaled that of the crime family they portrayed.

His friends remain fiercely protective; to give just one example, Sopranos co-star Steve Schirripa began our interview by demanding, “Now, this ain’t a hatchet piece, is it?” The subject’s surviving family politely declined to participate in this biography, or did not respond to requests to do so. His son, Michael, thanked me for assembling several of these interviews, in their embryonic form, for a Vanity Fair tribute on the tenth anniversary of Gandolfini’s death, while emphasizing that his father would have appreciated the piece “because it focused on the work” (though that was not, in fact, the primary focus). His widow, Deborah, explicitly instructed one longtime friend who had worked with Gandolfini late in his career to answer only my questions about their professional relationship (“she would prefer I respect that Jim always kept personal stuff private,” he explained).

In both cases, the attempt to compartmentalize the actor and his work, the art and the artist, is as ill-advised as it is impossible. Those who worked with Gandolfini remember him fondly not because of the brilliance of his acting (or at least not solely), but because of his personal and professional grace. “He was everything,” Joe Pantoliano says, “pragmatic and hardworking, and he devoured life.” Viewers who find his performance as Tony Soprano spellbinding are often doubly impressed to discover how far removed he was from the character—that in real life, he was a soft-spoken, kindhearted, genuinely modest average Joe. “He would say to me, before the season, ‘Let’s go down to Little Italy, have dinner,’” Schirripa recalls.

“‘I want to just be around, kind of get the feel of things again, you know.’ Jim was not Tony Soprano. He was a Birkenstock-wearing, music-loving guy. He was kind of a hippie. He was not that guy at all.” And so a curious viewer might want to know how such a teddy bear created such a monster, and how his warm personality may have contributed to the otherwise inexplicable affection they feel toward this amoral gangster.

Yet it’s also difficult to know who James Gandolfini really was because, like many complicated men of a certain age, he was different things to different people. Some didn’t even know him by the same name. “It’s funny because you can tell when somebody met him by what they call him,” explains his longtime acting partner and coach, Susan Aston. “When I met him, he was James, and he didn’t start going by Jim till later.” Throughout his fifty-one years, he was known by a variety of monikers, in varying circles of friends, family, and collaborators—Jamie, Bucky, James, Jimmy, Jim—his rotation of affectionate nicknames a handy symbol of his ability to shed and shift skins while remaining, all the while, the same shy kid from Jersey underneath. Crossovers could get confusing. “One of my best friends is Aida Turturro,” says Gandolfini’s high school classmate Karen Duffy, “and she was doing Streetcar, and she kept telling me about James. And then when I saw it, I was like, ‘Ooooh, OK’—I didn’t put it together, that her James was my Jimmy. Or my other friend Vince, we worked together as oyster shuckers, and he was roommates with a guy named Bucky who also was from New Jersey. And I was like, ‘Yep, don’t know a Bucky.’” Gandolfini’s eventual (and, it seems, preferred) nomenclature of “Jim” became known outside of his orbit during the run of The Sopranos, when any scrap of information was welcomed and scrutinized.

Jim.

Jim.

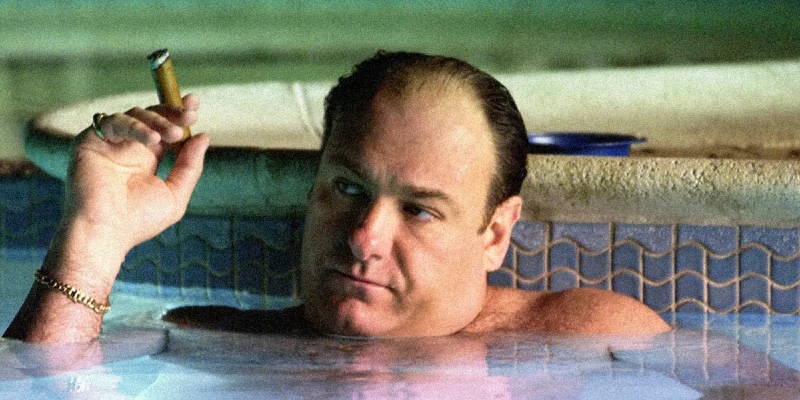

It seemed so uncharacteristic, so entirely at odds with the man on our televisions week after week; Jim was your milquetoast uncle, your rec center volleyball coach, your best friend’s dad who wore those awful tube socks with loafers. This man on HBO every Sunday, this king of crime, dressed to the nines, puffing on a Cuban, making men quake in their boots with a word or merely an impatient glance—that was not a Jim.

But it was. And as he embarked on a life and career beyond that iconic character, James Gandolfini was faced with something actors must often conquer: an identity crisis. He wanted to play characters who were as divergent from Tony as he was (and when he did play criminals after, they would pointedly not recall Tony Soprano; if anything, they would subvert the image of power and cool he’d defined in that role).

And so, to understand Jim, one must first grapple with the gulf between Jim and Tony—and how its depth and breadth were often variable.

The sainthood of James Gandolfini began almost immediately after his death. Two days hence, Schirripa penned a heartfelt testimonial in the New York Post, telling (among other tidbits) the story of how, after a bitter and public salary renegotiation with HBO, Jim wrote giant checks sharing the raise with several of his co-stars. It became a key piece of Gandolfini lore, and a quintessential Jim story: an act of jaw-dropping generosity, done without fanfare, and to be kept between the giver and the receiver (if not in total anonymity). In the passing years, similar stories would surface, bound by the common thread of Gandolfini’s kindness, consideration, and modesty.

In the dozens of interviews conducted for this book, I would hear these stories and more, tales of actorly camaraderie, friendly encouragement, and financial munificence. But the portrait of Jim Gandolfini as selfless martyr is as simplistic and unrealistic as that of Jim Gandolfini as Tony Soprano. As I spoke to additional friends and collaborators, a more complicated portrait emerged, of a man whose personal magnanimity often coexisted uneasily with professional selfishness, and whose (to borrow the most oft-intoned term) “demons” resulted in a recklessness that sometimes frightened those around him.

He was not simply one thing or another—neither a saint nor a sinner, but a guy, an uncommonly talented, undeniably complex, warm, self-lacerating, accommodating, short-fused, charitable, working-class, free-spending, hard- drinking, hard-partying, hardworking, hard-living twenty-first-century man. “He was a searcher, really,” said Sopranos creator David Chase. “Whatever the opposite of bullshit is, that’s what I think Jim Gandolfini was searching for.”

___________________________________