I missed my chance to be in a cult. In my twenties, a guy on the street handed me a pamphlet to join a “communal farm”—an obvious cult. Nevertheless, I was intrigued: maybe I could enjoy this farm’s bucolic vibes and free love, while shrewdly avoiding any mass suicide, or baby-eating, or barnyard chores.

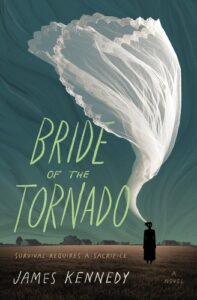

I never did join that cult (although I’ve taken improv classes). Even still, my horror novel Bride of the Tornado is about a small town in thrall to a secret tornado cult.

But don’t storytellers have something in common with cult leaders? Cults recruit people, suck them in, and trap them in their weird reality . . . just like authors! Both take an apparently random protagonist, establish they’re important, initiate them into an extraordinary world, and abuse them to a transformative breakthrough point. Pretty much Campbell’s Hero’s Journey!

Still, while many stories chronicle one’s initiation into a cult-adjacent world—whether it’s Rowling’s Hogwarts, Donna Tartt’s Hampden College, or Proust’s high society—sometimes storytelling itself is the cult.

The movie Midsommar didn’t just brainwash its heroine Dani; it brainwashed us. After the Scandinavian cult killed all of Dani’s companions and she gave her creepy concluding smile, I whooped, “You go, girl! Your inconsiderate boyfriend and his jerky friends had it coming!” Wait, what? How was I manipulated into yas-queening murder?

Then it hit me: storytellers are manipulative cult leaders. And if that’s not totally true, it’s 70% true—good enough for the internet. Let’s see how! (And if you want to go deeper, I do an episode about this on my Secrets of Story podcast.)

Getting a new member, or “Target,” committed to your cult (or story) takes four steps:

- 1. RECRUIT THE TARGET

Here are the “seven properties of easily brainwashable people”—properties perhaps shared by impressionable readers who we might convert into cultlike fans:

1. Desire to belong. (Many bookworms are shy and looking for their tribe.)

2. Reluctant to question authority. (As readers, aren’t we assenting to someone else entering our heads, controlling our thoughts?)

3. Gullible. (Something like gullibility must be essential to enjoy unreal narratives.)

4. Needs questions answered in black-and-white terms. (Fans often get anxious about contradictions in the “canon” of their imaginary world.)

5. Feels culturally marginalized. (Therefore open to the new culture you’re offering?)

6. Naively believes everyone is good. (Some readers are always upset when characters are “unlikeable.”)

7. Believes life has a higher purpose. (Readers crave uplift or transcendence by the end of the story.)

From this list, here’s my modest proposal: if a writer wants cult-level fans, they should write for the dependent, unassertive, gullible, black-and-white thinking, frustrated, naïve spiritual seeker. They’re more likely to commit to your book with cultlike fervor!

With our Target pinpointed, we move on to:

- BREAK DOWN THE TARGET’S IDENTITY

A cult leader must disrupt a Target’s identity: isolating them from friends and family, censoring their intake of information, exhausting them so they don’t realize what’s happening to them—even using malnutrition or sleep deprivation.

But when you’re reading a book, how is that so different? With a good book, the reader is literally immobilized, their attention fully absorbed, their internal train of thought hijacked and redirected by the writer—especially when the reader really “identifies with” a character. An absorbing book even makes the avid reader forget to eat (malnutrition: check!) and stay up all night reading (sleep deprivation: check!).

And just as cult candidates must be separated from their ordinary world, so we must separate our Target from normal people. One way to do that is through language.

Cults often invent bizarre jargon (Scientology has “thetan,” “preclear,” “upstat,” etc.) and force new definitions onto normal words (Scientology redefines “audit,” “tech,” etc.). And just as Scientology dubs those who resist their teachings “suppressive persons,” we all know that Harry Potter’s “muggles” are those ignorant of concepts like “quidditch,” “animagus,” or “expelliarmus.”

Once your Target is speaking a cult-language, it’s easier to keep their thoughts cult-approved—and weird jargon makes them repulsive to outsiders, causing them to turn back to you, bonding even more strongly. Win-win! And just as Catholics feel a justified distaste when a non-Catholic calls the Eucharist a “cracker,” your Target will feel superior when outsiders bungle their terms, like when my Aunt Lorna would call C-3P0 “Three-Seepio.” (AUNT LORNA!! YOU’RE GETTING IT WRONG!!! AND IT’S “STAR WARS,” NOT “THE STAR WAR”!!! GOD!!!!!!)

In a cult, the Target acquires a new cult-provided name, clothes, and social life. Similarly, if storytellers do their job properly, the Target transfers their identity to fictional worlds. That’s beyond merely dressing up as their favorite character for Comic-Con. It means paying thousands of dollars to go to Star Wars and Harry Potter theme parks. It means Trekkies learning to speak Klingon. It even means becoming clinically depressed because you can’t actually visit Pandora from Avatar. This leads to the third step:

- EXHAUST THE TARGET WITH STRESS

Now that our Target is invested in our new world, what must we do? Punish them!

Wait, why punish your audience? Oh, honey. Don’t you know the first thing about people? They love being punished! That’s the secret sauce that both cults and storytellers use.

We’ve already dangled before the Target delights only the cult can provide. But folks feel contempt for those who treat them too well. So once you’ve made the Target feel amazing, you must yank out the rug from under them, and relentlessly bully them. They’ll thank you for it with unending devotion!

This is accomplished on two levels. It happens in the story itself, where the protagonist gets subjected to ordeals. The reader is brutalized by proxy, and takes furtive delight in that. (Before literary folks get smug: nothing but a craving for others’ pain got you through 800 pages of Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life.)

This also happens in the storyteller-audience relationship. Doubt me? Um, have you watched any new Star Wars lately? What started out in 1977 as a thrilling adventure is now a total chore. And that’s by design! People are committed to Star Wars now because it’s so bad. I was midway through Ahsoka when I realized: this is painful! And yet I watched it all. “I gotta give it a chance . . . if I watch the Clone Wars cartoons, maybe I’ll understand . . . it’s my fault . . . I’m not a good fan!” Willingness to absorb punishment proves you’re a good cult member.

If something is entirely wonderful, it betrays our desire for necessary garbage. The first three Harry Potter books are good—big problem! The audience wasn’t being punished enough. Rowling, an effective sadist, eventually gave her audience what they really wanted: four 700-page books in which the good was properly mixed with the turgid, confusing, and unnecessary. In the fifth book, Harry and his friends spent so many pages cleaning an apartment I felt I was in a Haruki Murakami novel. But reading it confirmed me as a true Potter fan. I suffered! I was worthy!

Again: this isn’t limited to genre readers. People either hate Joyce’s Ulysses or they become Joyce fanatics. They suffered through reading it, and that suffering must be worth something . . . right?! (Full disclosure: I’m a Joyce fan—the kind of person who loves the punishingly complex.)

Which brings us to the fourth, culminating step:

- BECOME ONE WITH THE SECRET KNOWLEDGE

We’ve brought the Target into the cult, broken them down, given them a new identity, and punished them so that they’ll follow us anywhere. Now here’s the highest level: nonsense.

The best gift a cult or story can provide is pointless complexity that the Target can puzzle over for the rest of their lives. Every cult needs an attractive public-facing side (fellowship and community!) and bizarre, embarrassing secrets (look up “Lord Xenu”).

After you’ve hooked the Target with your charming, straightforward story, you must steer them into esoterica. Start with a lighthearted romp like The Hobbit; lure them into the more complex Lord of the Rings; suddenly the reader wakes up on page 400 of The Silmarillion, muttering about Akallabêth and Númenor. You got ‘em, bud!

Once your Target is in the fold, they need difficulties to fascinate them. This should take the form of contradictions and paradoxes, so acolytes can spend all their mental energy reconciling impossibilities in satisfyingly elaborate ways. Whether it’s the doctrine of transubstantiation, or retconning inconsistencies of later seasons of “Doctor Who” into earlier ones, it’s the same: at the most exalted levels, you must blatantly contradict yourself and pass it off as paradox.

The human mind hates consistency! It prefers to exhaust itself shuttling back and forth between incompatibilities that it’s obliged to reconcile. To start a religion (or a story) that lasts, make it artfully incoherent. Bringing your Target into full communion with higher nonsense is the glorious culmination of our work as artists and cult leaders, for it keeps us alive in the Target’s mind long after they have forgotten the straightforward and rational.

And if you doubt me—may I introduce you to David Lynch fans?

Thus endeth the lesson. Please use this knowledge for good, not ill. But if I see you on the street with a pamphlet—no offense, but I gotta keep walking. I’m trying to start my own flock here.

***