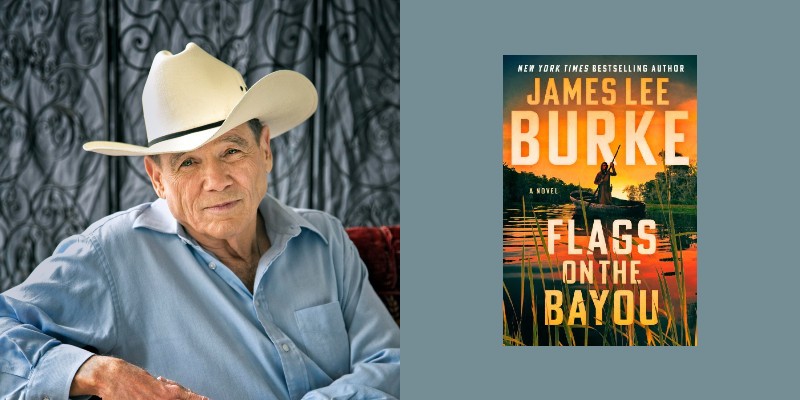

James Lee Burke, the modern master of all literature crime and noir, returns to shelves with his new novel, Flags On the Bayou. Continuing his recent exploration of American history through riveting stories, replete with his poetic and electric prose, Flags On the Bayou places readers in the violent upheaval, political chaos, and moral crucible of the Civil War. Burke’s deft narrative touch features the voices of several characters, including a runaway slave, a diabolical military leader, and a colorful cast of rebels and union loyalists navigating conflicted philosophies and emotions.

Burke’s work provides Americans with an opportunity to inspect the mythic properties of their historical conceptions, the generational trauma of injustice, and the perpetual collision between idealism and iniquity in the shaping of society. More broadly, it casts a searchlight on the eternal tangle between good and evil in the human heart.

I recently spoke with James Lee Burke over the phone, continuing an interview series I’ve conducted for CrimeReads.

David Masciotra: Your recent work deals heavily with American history. What is the reason for shifting from contemporary stories to those that more closely scrutinize American history?

James Lee Burke: That’s a very good observation you make. My compulsion throughout my entire life has always been historical. I think that the past, as Faulkner said, is not even the past. We’re still in it. To try to block it from our lives, as we have a way of doing in this country, because we’re still a young Republic, is an invitation for disaster. American history is extraordinary. Much of it is beautiful, but much of it is horrible, and we try to deceive ourselves about the latter. Writing now, it is clear that we’ve recreated the 1840s. We’ve brought back the era of nativism. The Republican Party has become the Know Nothing Party. Donald Trump is just a vulgarian who has stumbled his way into darkness with the help of very angry people. Writing about history makes sense, because it is the same group.

David Masciotra: Let me preface our conversation about the excellent new novel with this: Steve Phillips, a brilliant political thinker, has a recent book, How to Win the Civil War: Securing a Multiracial Democracy. A great historian, Heather Cox Richardson, has a book, How the South Won the Civil War. While reading your novel, I couldn’t help but put you in their company, because it seems as if you are attempting to make us consider how the Civil War never ended.

James Lee Burke: That is absolutely correct. I have not read the work of these scholars, but I would certainly agree. It was never over. The joke down South is, once in awhile, someone will shout out, “Those damn Yankees are spreading rumors that they won the war.”

David Masciotra: Do you have a research process when writing historical fiction?

James Lee Burke: No, I don’t research. As I go along, I might check small things. This may sound grandiose, but I think if you have to research a subject to write a novel about it, maybe you should choose a different subject. You have to be a player. You have to go back into time to discover yourself, in your position in that time, because it is there. You see, human beings have never changed. One of the most influential historical books that I read is The History of the Church by Eusebius. It is the hands-on story of the Roman Empire in the Fourth Century. It is extraordinary, and as you read it, you realize that it is here. We have the same players, the same arguments. Nothing has changed.

David Masciotra: I find it quite interesting that you write this new novel with rotating narration, each chapter has a different narrator. How did you decide on that structure?

James Lee Burke: That comes from William Faulkner’s beautiful book, As I Lay Dying – one of his best books. Faulkner’s great gift was not only the substance of the stories, but his devices. I always told students that if they want to learn how to read and write novels, read As I Lay Dying and The Sound and the Fury. Those two books have no peer – nothing comes close.

David Masciotra: Faulkner’s inspiration was often similar to yours – Southern Reconstruction, race, oppression and idealism. Did the substance of his novels and short stories influence your treatments of these topics?

James Lee Burke: That is correct about Faulkner, but no, the substance of his novels did not influence the way I tell these stories. That comes from my father. My father was an amateur historian, and he wrote very good prose. He was an engineer who always wanted to be a journalist. The stories in Flags On the Bayou were real. That’s the way it was. I heard them over and over again when growing up. When I was young, I said something about the rebel yell, and my father told me, it’s not what you think. His grandfather was with Lee and Jackson through the entirety of the Shenandoah campaign. It was a fox call, not a scream. It was a light, “woo.” But you’d have twenty thousand guys doing that coming over a hill. It would scare the heck out of everyone. My great grandfather was at Gettysburg. His name was Robert Perry. He was a lieutenant in the eighth Louisiana Volunteers. He was in two invasions going uphill into Yankee fire in three days. A very low percentage of those involved in the Civil War on the Southern side had anything to do with slavery. In fact, most of the men who enlisted were poor. So, the story is more complicated than “the bad guys were slavers, and the Union guys were angelic.”

David Masciotra: Flags On the Bayou explores the atrocities of the Union army. The historical record is quite clear that these atrocities happened, but it is almost never acknowledged. Is that why you wanted to insert those into the novel?

James Lee Burke: Yes, absolutely. In reality, the Civil War, as it was orchestrated, was a testing ground for a genocidal policy that destroyed 50 million bison, and wiped out the American Indians. It was calculated, and the leaders were open about it. William Sherman was a terrorist, and he was proud of it. Grant supported Sherman. They declared war on civilians. Lee did the same thing, one time, in Chambersburg. He turned his troops loose on the civilian population. They took freeborn Black men and women, and forced them into slave auctions. It was a disgrace. It was a Louisiana unit that did it, and I hope it wasn’t my great grandfather’s. The American terror against the indigenous population continued, of course, long after the Civil War.

David Masciotra: Speaking of slavery, you write richly in the voice of a slave, Hannah. I don’t feel this way, but there are some who would object that it is inappropriate for a white author to write in the voice of a Black woman. Are you aware of that objection, and did you have it mind when you wrote this novel?

James Lee Burke: I am aware of it. In terms of logic, the people who have this point of view need to reevaluate the implications. So, a man cannot write in the voice, or maybe even about, any women. He can’t write about his pet dog. If he hasn’t had a child, he should not write in the voice of a parent. If a person has never suffered poison ivy, he cannot write in the voice of someone who has suffered poison ivy. And Michelangelo – what gave him the authority to paint that ceiling? He’s knew nothing about being God.

David Masciotra: It must feel like an odd time to be a writer, because simultaneous with the growth of that restrictive mentality on the left, there is a right wing effort to ban books, like yours, that depict issues of injustice and crimes of our history. What is your reaction?

James Lee Burke: It is fear, just like always. The poor, Southern white man was taught to fear and hate the Black man. Did you ever read the John Grisham book, The Chamber? In the story, a Klansman is about to be put to death. The warden asks him for his last words before going to the gas chamber. He says, “There are many men in my life that I hate, and the one I hate the most is myself.” What a line. That is what the oligarchic leadership taught the poor whites – that the Black men and women, the Latino immigrants, the Native Americans are their enemy. And that their intrinsic worth derives from their persecution of the other. As I said earlier, the people trying to deny history are making a disastrous mistake.

David Masciotra: Flags of the Bayou is a violent novel, but the violence is never gratuitous. It acts as a predicate for an exploration of history within the context of your characters. Do you have a philosophy for using violence in storytelling, because you do it quite well?

James Lee Burke: Thank you. Most of the time the violence is off camera. A passage should allude to the violence, but not describe it in detail. Also, the violence that I’ve written about is not simply that of morally impaired people. It is something worse. It is a cancer on the soul. It is something that they bear inside them. They are pathological in their hatred. The South is full of these people, but now it is no longer regional. It has gone national. Trump did that. It also has a twisted theological dimension in that derives from a belief that their God is the enemy of their enemies. So, the violence should point to something much larger, as you say.

David Masciotra: I see that you have quite an itinerary. You have a new short story collection coming out in 2024, as well as a new novel. You also have another new novel coming out in 2025. How do you remain so prolific?

James Lee Burke: It’s one of the advantages of neuroses. It never fails you. It is always there. The energy goes night and day, and it’s free! More seriously, it is just a compulsion. I’ve never wanted to do anything else. When I was in the fifth grade, my cousin and I tried to write a story for the Saturday Evening Post. I published my first story when I was 19, and finished my first novel when I was 23.