The late Toni Morrison wrote, “Those writers plying their craft near to or far from the throne of raw power, of military power, of empire building and countinghouses, writers who construct meaning in the face of chaos must be nurtured, protected.”

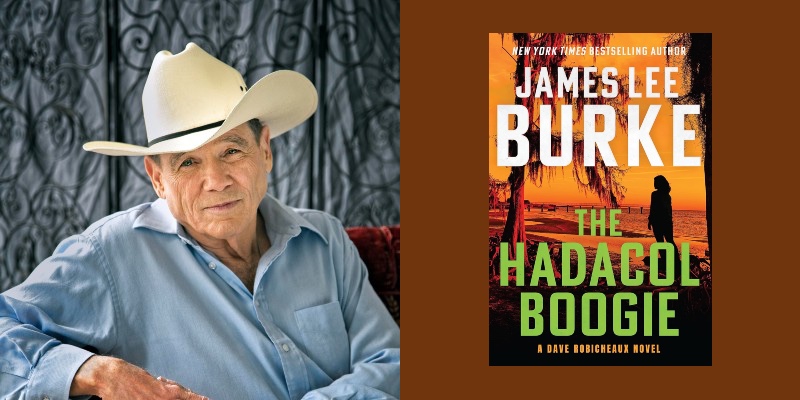

James Lee Burke is one of those writers.

Over the course of 44 novels and three short story collections, Burke has issued lyrical defiance of the poison and pablum of power. His sword-like pen moves at rapid, but deliberate pace to expose the induced chaos of political corruption, bigotry, and state-violence, while also underlining the shimmering humanity of people who maintain virtue and demonstrate heroism far outside the palatial rooms of wealth and glamour. He manages to explore the most crucial topics of human nature and American history without ever falling into didacticism, but instead writing stories that transfix the reader.

His latest books updates the chronicles of Dave Robicheaux and Clete Purcel. The Hadacol Boogie, set in the early 2000s, has the familiar Burke heroes and the new character, Valerie Benoit, a crusading African American detective, investigating the brutal murder of a young Black woman. The riveting story leads them into a confrontation with not only the criminal underworld of Louisiana, but also the dark side of themselves and their country’s history.

Burke and I recently spoke on the phone about his latest novel. The interview that follows is the latest in a series that I have conducted for CrimeReads since 2020.

David Masciotra: The Hadacol Boogie has a much darker tone than most Robicheaux books. Is that a correct read of the book, and if so, from where does that darkness derive?

James Lee Burke: Yes, that is correct. In fact, I’m glad that you saw that darkness. I hoped that when the reader would gather with these characters in the pages that it would feel like the fourteenth century in that it is a time when it is like there is a shifting of the equators. It isn’t quite demonstrable, but we are in an era that we don’t quite understand. It is a time when we have to make big choices – big choices politically, big choices ecologically, big choices ethically – and yet we don’t have the necessary experience and knowledge to make those choices. In the novel, Dave senses all of this. He can’t quite articulate exactly what it means, but he remains Chaucer’s good knight. So does Clete. I think of them as our beacons, and I hope that the reader will as well.

David Masciotra: Because what you are describing about the time in which we live is difficult to classify in precise terms, do you believe that literature allows us to gain a better understanding, or at least, sense of it?

James Lee Burke: Absolutely. We call it, “literature,” but the other word is “art.” Art is form. It is the presentation of something intangible in a tangible form. I was a student of John Niedhart at the University of Missouri. He was the author Black Elk Speaks, which is a beautiful and spiritual book. I’m very much influenced by him. He told me when I was 21-years-old, “Jim, you have what it takes to be a great artist. You aren’t one right now, because your work is like a handful of diamonds and rubies. Once you find your form, you will become a great artist.” He promised that I would be surprised by the form that I would find for my work.

David Masciotra: When do you feel that you found your form?

James Lee Burke: It is difficult to say, because I believe that it is in the unconscious. It is in the hours of our sleep, which is what Hemingway thought. Sometimes it is hard to teach creative writing, because the most talented people aren’t the most dutiful students. They’re the crazoids waiting for something at four o’clock in the morning. With all true artists and journalists, they know that they have a gift, and they just have to have the patience and stillness to wait to see it. Then, something will happen, and it’s like, “Wow, there it is.”

David Masciotra: In our previous conversations, we’ve discussed your historical novels. Even though this book is set in the recent past, it deals pretty intensely with American history, particularly the horrific treatment of Black Americans and the horrific treatment of Native Americans. Why do the dark episodes of our history play such an important part in this story that is set in the year 2002?

James Lee Burke: That’s a great observation. The nineteenth century was one of the most violent in human history, and the twentieth century was the most violent. My generation lived through much of that, and the America where we grew up for people born during the Depression, we will never see again. For good and bad, we will never see those traditions and that culture again. To your point, Americans must understand that something occurred in the nineteenth century, and in order to come to terms with our history, we must accept it. We still will not accept that that the something that occurred was the practice of genocide against the Native people. It was 1891 that the destruction of the Sioux tribe took place, and the next hundred years was one of the bloodiest times in human history. We deny it time and time again, and look, we’re still in it.

David Masciotra: What are the costs of that denial?

James Lee Burke: Denial is why we are doing it again. We have a president who is killing people now. There is blood all over his hands.

David Masciotra: It struck me as a powerful commonality that Renee Nicole Good received her training at a church by the name of St. Joan of Arc. Joan of Arc is a hero to Clete Purcel. Clete even believes that, on occasion, he converses with her. Why is Joan of Arc a continual reference in your books?

James Lee Burke: She was such a wonderful person, and so vulnerable. At age 17, she led an army, and yet she never drew blood. She was probably raped in a tower after her capture. It’s awful to think about. She had a friend who was a sergeant in arms who rode behind her, and reportedly, he had massive arms and a gut like a beer keg. Well, if Clete was in the fourteenth century, that would be him. She was betrayed and burned at the stake. When I think about her story, I think, “How can humans do this to each other?” Her story is our story. It is justice, it is betrayal, and it is cruelty.

My thoughts on American history are similar, which is why I always bring it up in the novels. Why did we kill so many of our neighbors in the Civil War? Why did we kill so many of the Natives, most of whom were peaceful people?

But through it all there is still virtue and still those who fight for it. I always side with George Orwell who wrote, “When it comes to the pinch, human beings are heroic. Women face childbed and the scrubbing brush, revolutionaries keep their mouths shut in the torture chamber, battleships go down with their guns still firing when their decks are awash. It is only that the other element in man, the lazy, cowardly, debt-bilking adulterer who is inside all of us, can never be suppressed altogether and needs a hearing occasionally.”

David Masciotra: You’re speaking of all of these major topics of history, and even though your work transcends genre and there are always problems with separating works of art in labelled genres, I’m curious what you think crime literature brings to these subjects, such as ethics and history?

James Lee Burke: I think of the Robicheaux books as more than genre books, but that isn’t to say that genre books are bad, I mean my God, Mark Twain wrote genre books. I would say that it is through dealing with mystery that we can explore the great mysteries of the world. Look back to the Ancient Greeks and Romans, they developed metaphors for deciphering the great mysteries of science and philosophy and theology. Contemporary mystery stories can have the same metaphorical power.

One of the problems is that we have all of these fascinating questions and stories at our fingertips, but so many people aren’t interested in them. And there are powerful people who want us to remain disinterested. The dumbing down of America started around 40 years ago, and it continues to get worse.

David Masciotra: Why do you think it started then?

James Lee Burke: The rich and the powerful fought with the government for 100 years. They fought against the Roosevelts and the Kennedys, but then they wised up, and they said, “Let’s stop fighting them, and just buy them.” And that’s what they did with Ronald Reagan, which was around the same time that they started their media companies, their attack on education, and they got Reagan to undercut the media regulations that demanded fairness and accuracy in the news.

David Masciotra: Getting back to Robicheaux and Clete, you make sure to emphasize their kindness, even tenderness, in the way that they care for children and animals. That’s a refreshing change from the typical macho crime hero. Why is that something that you always include in your stories?

James Lee Burke: It goes back to what we were discussing earlier. It is a reflection of the fourteenth century and Chaucer. The knight-errant had an ethos of compassion.

David Masciotra: Why is Chaucer such an important influence over your narration of Clete and Dave? You’ve mentioned him twice now.

James Lee Burke: Well, the Canterbury Tales is about a pilgrimage, and all the players of England – all the different kinds of people of the Middle Ages – are in these stories. They’re always getting into trouble. There is chaos. But there is the good knight who is a man of honor. He’s kind, and he’s a spiritual man. If we turn our backs on these stories, along with Shakespeare and Elizabethan theatre, we miss out on such a profound source of insight. But there is also great fun in the Middle Ages, and I try to make that quality part of my stories as well. It was very festive. We’re in Dullsville now.

David Masciotra: Speaking of villains, The Hadacol Boogie, like previous Robicheaux novels, features malevolent characters who are cops. Why is it important for you to show the range of behavior from law enforcement?

James Lee Burke: It is reality. There are police officers like those we saw on September 11th, who rushed into the burning towers to save the lives of strangers. Then there are cops who are bullies, who use their power to prey on weaker people.

David Masciotra: You introduce a great new character in The Hadacol Boogie, Valerie Benoit.

James Lee Burke: She is a great character. She just walked out of nowhere. I never planned for her to be a big part of the book. She’s a courageous young Black woman who has a cross to bear. She confronts some racists in and out of law enforcement who give her a terrible time, but she’s heck on wheels herself.

David Masciotra: How does it change things for Dave and Clete to partner with her?

James Lee Burke: Well, they like her and they learn from her.

David Masciotra: My last question is about music. You title this new novel after a song that Jerry Lee Lewis and Buddy Guy performed together. Characters throughout the novel mention Jimmie Rodgers, Merle Haggard, and other artists. Why is music so often part of your novels?

James Lee Burke: I think music is the greatest art, and I think that rock and roll and country music are the best songs in the universe. Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis, Fats Domino, Elvis…I mean, those guys were geniuses. Go back and listen to their old music. You can’t believe it, it is so good. Little Richard played in Louisiana in the 1950s, a Black man in drag. I’m surprised they didn’t drop a hydrogen bomb on him. That guy had guts!