In 1944, Allied bombers flew missions from Italy to hit targets in Romania. Every day, hundreds of heavy bombers and their fighter escorts flew over the Adriatic Sea and Yugoslavia to reach their objectives. The German Luftwaffe had been weakened at this point in the war, so the enemy focused on bringing down damaged Allied aircraft, often flying alone at low altitudes on their return trip.

B-24 Liberator bombers over Romanian oilfields. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division LC-USZ62-97497

B-24 Liberator bombers over Romanian oilfields. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division LC-USZ62-97497

By August, the Allied bombing had intensified, and 350 bombers were lost to the Luftwaffe. Many of the crews bailed out; some came down in territory held by Marshal Tito’s Partisans, while others found refuge in Serbia with Draža Mihailović’s Chetniks.

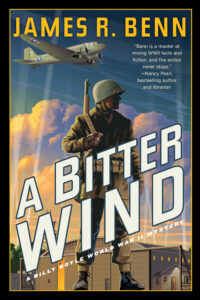

Before relating how these events are folded into the plot of the twentieth Billy Boyle WWII mystery A Bitter Wind (to be released 9/23/25), let’s take a time-out for a condensed lesson on the two major players in the Yugoslavian resistance.

Draža Mihailović was the leader of the Chetnik Detachments of the Yugoslav Army, a royalist and nationalist guerrilla force established following the German invasion of Yugoslavia in 1941.

Josip Broz, known as Tito, was head of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia and led the anti-German resistance. The military arm of the Communist Party was known as the Yugoslav Partisan Army.

While both men wanted Yugoslavia to be liberated from the Nazis, there was a wide ideological gulf between them. Tito was aligned with Stalin and wanted to create a communist state. Mihailović was a monarchist and anti-communist. Mihailović’s Chetniks were the smaller force and believed in waiting until the Allies landed before launching an uprising, fearing reprisals. Tito’s Partisan Army favored immediate armed resistance.

Throw the Ustaše—a Croatian fascist force aligned with the Nazis and who committed war crimes against Jews and other minorities—into the mix, and you have a violent brew of betrayal and brutality.

But there was one group that was steadfast in their dedication to rescuing and caring for downed Allied airmen above all else—the everyday people of Yugoslavia. Farmers, peasants, and mountain folk all sheltered escaping aircrew. They shared what little food they had and hid the fliers, risking immediate execution if caught. Over two thousand airmen were extracted from Yugoslavia during 1944, the bulk of them from areas controlled by Tito’s Partisan Army.

Escaping American airmen hidden somewhere in Serbia. © 2022 Halyard Mission Foundation – Photo by J.B. Allin

Escaping American airmen hidden somewhere in Serbia. © 2022 Halyard Mission Foundation – Photo by J.B. Allin

While the Chetniks and Tito’s Partisan Army cooperated in the rescue of flyers, things were not always amiable between them. Atrocities were committed on all sides, and Mihailović was derided for making local truces with enemy forces. While the British and Americans had provided arms and supplies to both groups, airdrops to the Chetniks began to be held back

Finally, the Western Allies diverted all material support to Tito, totally abandoning the Chetniks even as they continued to rescue downed airmen at great risk. Much of this had to do with the internecine conflict between the Chetniks and Partisans, which diverted energies from fighting the Nazi occupiers. Then British agents, such as Kim Philby (later revealed to be a spy for the Soviets), heavily influenced by Tito’s communism, agitated against support for the Chetniks.

Military missions to the Chetniks were withdrawn, and only a few Office of Strategic Services (OSS) personnel were left in Serbia. Hundreds of Allied airmen who had been downed over occupied Yugoslavia and rescued by Mihailović’s Chetniks were left stranded. But despite the official directive to halt supplies going to the Chetniks, US Air Force General Ira Eaker ordered the creation of the Air Crew Rescue Unit to work with Mihailović and bring out the remaining airmen. This effort was code-named Operation Halyard.

It’s at this point that the fictional plot of A Bitter Wind intersects history. Captain Billy Boyle is investigating the murder of an American officer at a top secret airbase in Great Britain. The secrecy has to do with radio interception technology, and the one person who has information about the crime has just been shot down on a bombing raid. The Lancaster bomber crewman possesses classified information about electronic warfare as well as potential knowledge about the murderer.

So off goes Billy, first to Italy, where he boards a C-47 transport plane for the dangerous trip into the mountainous regions in Serbia, to ensure the rescue of his witness.

Now back to the history lesson. When the Air Crew Rescue Unit began working with the Chetniks in July 1944, they found over 250 airmen in and around the village of Pranjani, an isolated Serbian village which served as the headquarters of the Chetnik forces. Many of them were injured or sick and had been brought in from across Serbia to await deliverance. But first, an airstrip had to be built. In the mountains. Without equipment. Surrounded by German and Ustaše soldiers patrolling nearby, and with a Luftwaffe airfield only twenty miles away.

OSS operatives and airmen in front of a C-47 at Pranjani. Source: US National Archives

OSS operatives and airmen in front of a C-47 at Pranjani. Source: US National Archives

The airstrip had to be constructed in complete secrecy, with most of the work done at night by more than a hundred diggers with ox-drawn carts. The digging, leveling, and felling of trees were carried out with only the most basic of tools. When work was done in daylight, farmers stood ready with small herds of cattle to drive them out in the fields at the first sign of German aircraft, to cover the obvious marks of excavation.

The airstrip was completed in nine days. At one end was a thick forest, and at the other was a sheer drop-off. The strip was 150 feet wide and just over 2,000 feet long, barely enough for a safe landing.

The first flights out of Pranjani brought out the 250 men, twenty-five at a time. But more downed fliers kept coming in. Finally, at the very end of 1944, the Air Crew Rescue Unit was able to cease operations, having brought out a total of 432 US and 80 Allied personnel. Operation Halyard was the largest rescue operation of American airmen in history.

A column of American fliers makes its way to the airfield at Pranjani. © 2022 Halyard Mission Foundation

A column of American fliers makes its way to the airfield at Pranjani. © 2022 Halyard Mission Foundation

These fliers knew that their government had halted all support for the Chetniks, even as the Chetnik fighters were holding off German attacks. A heartfelt ritual emerged as they said goodbye to their hosts. Once aboard the C-47, their shoes and warm flight suits, as well as highly prized sidearms, were thrown down to their Chetnik friends.

The rules forbidding support for the Chetniks were ruthlessly enforced. Mihailović once asked if he could send two seriously ill Chetniks to Italy for medical treatment, and the head of the OSS section agreed on humanitarian grounds. When the two men arrived in Bari, Italy, they were noticed by Tito’s Partisan representatives. As a result, the OSS section chief was replaced.

As successful as the Air Crew Rescue Unit was, the entire affair was kept quiet as the Allies threw their support behind Tito, who also had the backing of Stalin. The sacrifices of the Chetniks, a possible embarrassment to American and British politicians, were swept under the rug.

In A Bitter Wind, I’ve stretched the timeline a bit to have Captain Billy Boyle racing to find his witness and catch the last flight out of Pranjani in the first week of January. But he must evade the Germans and the Ustaše, as well as a threat from an unexpected quarter in order to make his way safely to the Pranjani airfield.

After the war, Draža Mihailović was arrested by Tito’s newly established government. The charges involved his truces with the enemy and attacks on supporters of Tito. Support was organized by many grateful American veterans who had been saved by the Chetniks. Regardless, Mihailović was found guilty of high treason in what was a Stalinist show trial. Executed on July 17, 1946, his final words were:

I wanted much; I began much; but the gale of the world carried away me and my work.

Draža Mihailović, leader of the Chetniks. First published in Yugoslavia, 1943, and is in the public domain because its copyright expired pursuant to the Yugoslav Copyright Act of 1978 which provided for copyright term of the life of the author plus 50 years, respectively 25 years for photograph or a work of applied art.

Draža Mihailović, leader of the Chetniks. First published in Yugoslavia, 1943, and is in the public domain because its copyright expired pursuant to the Yugoslav Copyright Act of 1978 which provided for copyright term of the life of the author plus 50 years, respectively 25 years for photograph or a work of applied art.

In 1948, President Harry Truman posthumously awarded the Legion of Merit to Mihailović for his contributions to the Allied victory in Europe. But news of the award was suppressed. Even thought it would have helped to rehabilitate Mihailović’s reputation, the State Department insisted that such recognition would antagonize Tito and hurt US relations with his government. Public recognition by the United States was not given until 2005, when the award was finally presented to the general’s granddaughter, Gordana Mihailović.

I hope A Bitter Wind will bring some measure of awareness to this largely unknown story.

For further reading on the subject, I recommend The Forgotten 500, written by Gregory A. Freeman, 2007.

***