T.S. Eliot had it right. “Good writers borrow,” he said. “Great writers steal.” What he meant was that a writer aspiring to greatness should be reading critically (always) to learn the boundaries of the craft from better writers and to then apply their triumphs in their own work, organically. I’m not a great writer but I try to get better with each book. And I certainly look to other authors (both in fiction and nonfiction) for inspiration on how best to construct a true crime mystery into a compelling narrative.

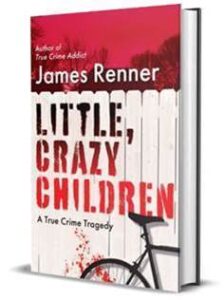

My next book, Little, Crazy Children, arrives June 27. It’s the real-life story of a teenage girl who was stabbed to death behind a mansion in Shaker Heights, Ohio in 1990 and the ensuing investigation to find her killer. When considering the structure and pacing of my narrative I returned to a few favorite reads for help. These five books contain different tools you might find helpful if you are ever compelled to write a true crime story of your own.

But keep in mind—the story you’re writing about involves real people in tragic situations. What comes across as a compelling story is often the worst day of a person’s life. The following writers never lose sight of the victim and their purpose in putting pen to paper is firstly to solve a mystery and bring closure where possible.

The Shadow of Death, By Philip Ginsburg

How do you write a compelling story about a mystery that has not yet been solved? Journalist Philip Ginsburg shows us how in this compelling search for the Connecticut River Valley Killer, who remains at large to this day. It’s a complicated case, with six victims discovered in various locations throughout New Hampshire and Vermont. But Ginsburg takes his time, vividly painting the scenery and telling us about each woman, in turn. And while there is no final resolution, it does present hope for closure one day.

The Wrong Man, by James Neff

If you’re writing a book about a miscarriage of justice and hoping to present a better theory of murder than any civil-servant prosecutor, you should study this book. It’s the story how Dr. Sam Sheppard was found guilty of murdering his wife, Marilyn —the crime that inspired The Fugitive television series. The narrative methodically builds a defense for Sam while revealing the real, likely killer. Neff, an accomplished journalist, shows the responsibility a reporter has to dig deeper and to find the truth in a mess of media and drama.

Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, by John Berendt

How do you make a murder story “fun?” By delving deeply into the eccentricities and histories of the people involved. Berendt has a knack for bringing out the humanity of the unique real-life characters surrounding this tale of an antiques dealer on trial for murdering a male prostitute. Take note of how he presents the town of Savannah, which becomes a character of its own.

Couple Found Slain, by Mikita Brottman

This true crime book breaks every convention of the genre and somehow still works. In fact I think it’s probably the best true crime book of the last five years. The murders presented in Couple Found Slain are not the central mystery. The mystery is this – what happens when a legitimately insane killer is sentenced to serve to time at a psychiatric hospital and then actually becomes sane? Brottman’s book triggers deeper ruminations on the nature of free will and the punitive bent of our justice system. If you want to learn how to include important themes in your writing, this is a master class for you.

The Colorado Kid, by Stephen King

Wait, what is Stephen King doing on this list? I’ll tell you a secret, King is a master of structure and I look to his books frequently to figure out how to construct a good yarn, even if it’s true crime. For instance, my book on the unsolved murder of Amy Mihaljevic shares the same narrative structure as King’s novel It, of all things. I think a story cries out for a certain, specific structure and when you find it, it quickly tells itself. Anyway, The Colorado Kid presents a compelling, unsolved mystery that may not actually have any logical conclusion. I thought about this one often while writing True Crime Addict.

***