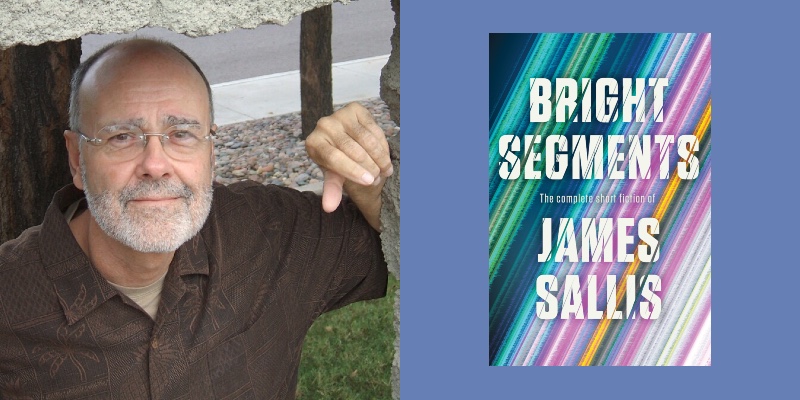

When publishers feel the urge to put out a retrospective of an author’s short stories, they often cherry-pick a handful of representative works—the literary world’s equivalent of a greatest-hits album. Then you have Soho Crime, which decided the lauded crime writer James Sallis deserved as maximalist a collection as possible: Bright Segments features 154 stories from across his entire career, packed into 800 pages.

If you’ve ever heard someone refer to a book as a ‘doorstop,’ this is exactly what they mean. It’s a tome weighty enough to crush a post-apocalyptic cockroach, and yet many of those stories are very short—no more than a page, in some cases. You can breeze through a decade of his output in an evening, if you feel so inclined.

For those readers familiar with Sallis primarily as the author of Drive (later adapted into an ultra-violent, neon-infused film with Ryan Gosling) and the Lew Griffin mystery novels, Bright Segments contains one big surprise: many of the stories are science fiction, a genre that Sallis has explored deeply throughout his life, bending it to his whims in all kinds of ways. There’s something in here for everyone, from the bleakly comedic “The Invasion of Dallas” (aliens find relationships just as confusing as humans) to the disquieting “New Teeth” (which comes off as a more ghostly “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?”).

But the book contains plenty of crime, too. There’s the original short story “Drive,” which became the kernel of the short novel, which mutated into the film. It’s also a pleasure to read that side of Sallis, smooth and funny and brutal.

In the following Q&A, I asked Sallis about the current state of the short story market, his approach to writing fiction, and a few more existential questions.

Q: You clearly have a career-long love of writing short stories—I was stunned at the completeness of this volume, and its thickness, especially since many of the stories are quite short. I found an older interview with you—I’m not sure which year, it mentions 2005 as the future—in which you detailed how the commercial short story market has essentially imploded in the decades since you began writing: if you want to get paid pro rates, especially in crime fiction, your available venues are rather limited. Do you think the market’s gotten worse since then, or do you think the rise of all kinds of online magazines and platforms has given a bit more breathing room to writers who want to focus on producing short stories?

JS: This, like all those concerned with publishing, is an extremely complex question. Are there, with online magazines and sites, more venues in which one might publish? Yes—though perhaps “publish” in this case requires, if not quotation marks, then some other modifier. There are hundreds of parking spaces hovering in the ether and available to writers. Do these venues, as did the array of science fiction or mystery magazines back when I was beginning as a writer and, later, a pool of highly visible literary journals, offer the sort of readership and presence that might bring a writer reasonably to anticipate writing as a lifelong pursuit?

Would Tom Disch have gone on to Camp Concentration or On Wings of Song without editor Cele Goldsmith pulling his stories from submissions to Amazing and Fantastic? Would Chip Delany’s Einstein Intersection or Neveryon tales be possible without the early support of Ace Books? Or for that matter, what of Ace’s publication of Ursula LeGuin?

When I began publishing, there were something like a dozen science fiction and fantasy magazines in circulation, plus a number of original anthologies like Damon Knight’s Orbit series. All were visible, all were read. More breathing room nowadays? I suppose so, but the current situation can recall Groucho Marx alone in a room, challenging his reflection in the mirror: Is that reflection real? counterfeit? duplicitous?

Q: Drive and other novels started as short stories. To paraphrase Nabokov, when do you know that a short story can grow the wings and claws of novel? Is it an intuitive thing?

JS: I’m first a poet; for me, everything is intuitive. Generally, story or novel, everything begins with a voice inside my head, a character speaking within the narrative, or the character in whose voice the narrative will be told. I start there: Who is this? Where is this? Anyone else there? Hello?

In the past I’ve spoken of this process as being akin to sensing a shape in the corner of the room, but it’s never there when I look straight on. Then, as I write, that shape begins to take on form. I can hear it breathe over there, begin see its borders; I am writing toward it. Elsewhere I’ve described the experience being like that of a jet taking off: gathering speed down the runway as it bumps along, moving faster and faster, till all at once in this heavier-than-air contraption you’re airborne, smoothly in motion, free, climbing.

Some narratives, like Cyprus Grove and Others of My Kind, announce themselves as novels upon first appearance. Most come together as I sit with the cursor blinking asking what next. It feels as though the voice gives me the first notion, the initial idea, then as I write, secondary ideas appear, strike against the first, and throw off sparks. It’s a physical thing, And from such collisions I recognize I’ve a novel at hand.

Q: Since I mentioned Drive: I’m a huge fan of your novels Drive (2005) and Driven (2012), as well as the movie based on Drive. How did having a movie adaptation of the first book impact the writing of the second one? How does seeing a director’s and screenwriter’s take on your character impact how you write about that character subsequently?

JS: What influence the movie may have had, was below any conscious level. I knew Driver’s world well; it was a place that, to revisit, I had simply to step back inside. We know the story in Drive, I thought, and we know from that novel how Driver’s life ends. So, what happens between his riding off into the sunset at the end of Drive and his being taken down in a Mexican bar years on?

I must restate my admiration for the movie. Seeing it at the premiere in L.A., I was spellbound. Does it differ from my book? Of course. The vocabularies of film and novel are different. But the pulse and blood of what I wrote is there. Nic told me on set that Drive was his take on my take. I said I hoped the two of them played well together. And they did—wonderfully.

Q: There’s a Wallace Stevens quote that I believe you use in one of your books: “The final belief is to believe in fiction, which you know to be fiction, there being nothing else. The exquisite truth is to know that it is a fiction and that you believe in it willingly.” But some of these short stories seem to blur that line between fiction and reality (or “reality”) ever so slightly.

I’m thinking specifically of “When We Saved the World,” the story in this collection that features Texas crime writer Joe Lansdale as a character; when I started reading it, I had this moment of slippage where I wondered if this was some kind of factual piece, before things started getting a bit too weird for what I accept as reality.

JS: Another complex question. I began, as you know, writing and publishing science fiction, within a short time, at Mike Moorcock’s invitation, moving to London to help edit the avant-garde science fiction magazine New Worlds. Mike introduced me to American crime fiction. In my flat off Portobello Road, I read all of Chandler and Hammett as I wrote and edited stories of other worlds, of futures near and far, of the permeability of experience.

As reviewer I was also met with a flow of books by European writers in translation: Julio Cortázar, Enrique Anderson Imbert, Boris Vian, Raymond Queneau. Cortázar in particular became a huge influence on my own work. In his stories, and in others like Queneau and Vian, I came upon something new, a realism that was palpably more, tales that insisted upon worlds existing beneath, beside, a step ahead or behind, of the visible one. A Cortázar character moves into a friend’s apartment and finds himself vomiting up tiny rabbits; all else in his life is like our own. For chapter after chapter a Jonathan Carroll novel feels mimetic, descriptive, like thousands of others, before the reader begins to sense something infirm, an inconstancy, as though a world with quite different laws and a quite different order is leaking steadily into ours. This seemed to me much closer to the way the world felt than any of the ways it’s generally put into words.

I was so taken with what was going on in these books that, first as writer and later as critic, I felt a new term was needed. Nowadays I use arealist fiction to include science fiction, fantasy, surrealism, anything atilt from the sensible world.

Q: In your books and stories, you’ve also spent quite a bit of time playing around with the nature of memory and fiction (now I’m thinking of “Silver,” one of the stories appearing for the first time in this collection, where the narrator remembers his mother telling him it rained on the day he was born, only for him to look up the data and see it was sunny). When you’re writing, how do you achieve the balance between driving the narrative forward—telling a kickass story—and weaving in these more meta or subterranean elements in a way that seems so smooth and seamless? When do you know when you’re “off-balance”?

JS: Intuition. A sentence is not just information. It has a weight to it, a valence, a charge. I go looking for each sentence, each phrase, to have such value to it: sound, rhythm, pitch, depth. “Get as much of the world as you can,” I told my students, “into each sentence you write. You’re not simply telling the reader this happened, that happened; you’re doing your best to recreate the experience.” Which is, of course, why each sentence, page, and scene gets rewritten incessantly.

Our lives are a construct of memory (past), experience (present), and anticipation (future)—and memory edited into fiction, which feeds those anticipations. So, pile all that on the creaking sentences as well, right?

As for telling the story, I’m from a commercial background, where narrative—momentum—is prime. My early stories were well paid for, appearing in established magazines and anthologies. And my early heroes were writers with a ready audience: Theodore Sturgeon, Edgar Pangborn, Alfred Bester. For me a major attraction of science fiction and, later, of crime stories, is the manner in which they provide a ready-made skeleton. The drive, the pulse, the substance is there. You can put almost anything on those bones, anything more, and it will all hold together.

Q: You’ve mentioned the line that separates “living as a writer” and “making a living as a writer.” You’ve taught classes, worked as a respiratory therapist for many years (which I assume influenced the story “Abeyance” in this collection), and done other jobs besides; and that’s in addition to writing 18 novels, the Chester Himes biography, and a mountain of short stories and essays. How have you balanced out such prodigious output with the rest of your life? What advice do you give to other writers who are trying for that sort of balance?

JS: Well, you pick up this wrist-breaker Bright Segments with its 154 stories and almost 900 pages and it looks like a heavy load, but remember, I’ve been doing this for over sixty years. That I endured at it owes much to my stubbornness but owes far more to the generosity of editors, other writers, readers, and booksellers who’ve been standing there by me through it all. I have been insanely fortunate in finding (or having been found by) extraordinary editors, again and again. I’ve had booksellers talking up the books to captive customers. Fine reviewers who saw precisely what I was getting at, sometimes when even I hadn’t. And—my emails and letters avow this—I have some of the best readers in the world.

Q: The short stories in this book cover an incredible span of time. When you were compiling and ordering these tales, did anything surprise you thematically? Did the stories in aggregate suggest you’d evolved as a writer in a way you hadn’t expected?

JS: I suspect that most of us evolve as writers in ways we’d not expected. Aside from embarrassment at the naiveté and clumsiness of some earlier stories, what was evoked in reading and re-reading yet again these stories, more or less in the order written, were floods of memory: where I was living at the time, personal circumstances, what I was likely reading, world events. Quite early on I could see what became my style or aesthetic coalescing, recall therefrom the influence of coming upon Cortázar, of J.P. Donleavy’s short stories, of Vian’s L’ecume des jours. A fine tour of my own and my nation’s history.

Q: You’ve said that the act of writing involves always challenging yourself, always pushing into new and potentially uncomfortable territory. What makes you uncomfortable on the writing front right now? What don’t you know what to do that you’re experimenting with?

JS: On the first day of every class I taught, I’d tell my writers “If you’re serious about this, if you dig in deep and stay with it, you will never be happy with what you write, you’ll always still be reaching.” The greatest danger of any creative work, it seems to me, lies in becoming professionalized, in learning how to do things, in failing to reach. The last time you wanted some effect or another, you did this—so you do it again, instead of taking this on as a new challenge to creativity. Stop. Let the cursor blink away. Put the paint brush down.

To return to your previous question, a major takeaway in re-reading all these stories was my realization of how I kept reinventing wheels and undercarriages and doors, again and again— because I didn’t know how to do all that.

We lose something important, I think, the moment we forget that art is play. Best to be the child looking at that sheet of paper. What can I do with this? And with this crayon? There are no rules. I can do anything I want. I can try. I can reach.