Rich Cohen’s Murder in the Dollhouse: The Jennifer Dulos Story is about a crime that stunned one of America’s richest towns. The 2019 disappearance of the New Canaan, Connecticut mother of five drew extensive news coverage—an example, some said, of “missing white woman syndrome.” Once again, the media was obsessed with a privileged suburbanite in mortal peril. Meanwhile, crime victims from other racial and socioeconomic backgrounds were largely ignored.

But to Cohen, the Dulos story transcends labels. “It was more than just the surface details that made the story mesmerizing,” he writes. “It was the horror, the universal nightmare, the way death arrived amid the quotidian details of an ordinary American morning.” Jennifer Dulos, just back home after dropping off her kids at school, was attacked by her estranged husband Fotis Dulos, who was charged with her murder. He killed himself in January 2020. Her body has never been found. Fotis Dulos’ girlfriend, Michelle Troconis, was convicted of conspiracy to commit murder and sentenced to 14 years in prison.

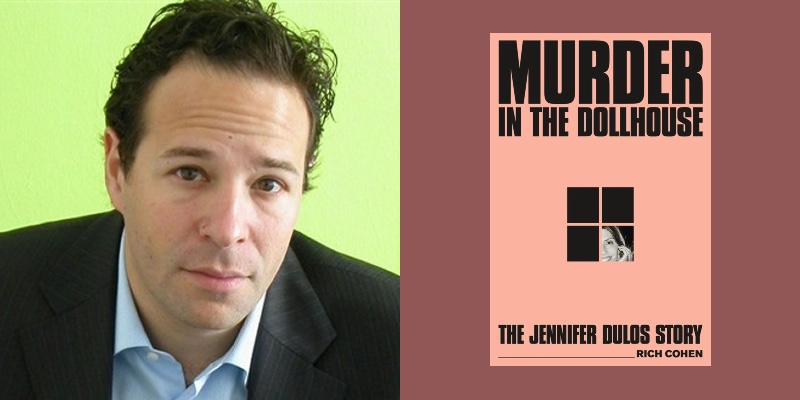

Cohen, who lives close to where the crimes occurred, covered the case for Air Mail, ex-Vanity Fair editor Graydon Carter’s digital publication. Speaking from his Connecticut home, the author of several nonfiction bestsellers discussed why he initially declined the assignment, how money is no guarantee of safety and what Jennifer Dulos’ unrealized dream of an idyllic family life says about her generation and its discontents.

How did you learn about the crime?

I heard about it from other parents. Small world—Fairfield County, Connecticut. People were very upset about it and also fascinated by it. It’s like your life in a funhouse mirror. Graydon Carter, the editor of Air Mail, knew where I lived. He was reading about it in the paper, and he suggested that I write about it. At first, I said I didn’t want to because it had been so (thoroughly) covered. It was something I didn’t want to dwell on.

But then just out of curiosity, because he kept asking, I got the arrest warrants. When I got into the details of their lives, I saw so many echoes of my own life and the lives of friends of mine. And in some weird way, by looking at this case, you could sort of see what was happening with my generation in America as we made our way through life.

You acknowledge at the start that the news coverage felt to some people like “missing white woman syndrome.” Why does this case transcend that label?

I’m not a crime writer and I’m not attracted to these stories. But I was attracted to this story because of the domestic ordinariness of it. It was this real horror that enters the most boring moment—dropping your kids off at school—and then she vanishes. She was a person of great wealth and had all the protections you could get. But you realize that ultimately none of us are safe.

The first third of the book introduces her in novelistic detail. She spent years in New York City working as a playwright but had always wanted to be married and have kids in the suburbs.

Part of the “dead white woman syndrome” is that the victims of these crimes are flattened out and dehumanized. What I found out was she was so human, so interesting. Yeah, she had a lot of money, but so what? She was a very artistic person who had an ideal of what domestic life would look like—perfect husband, perfect house. And she was obsessed as a little girl with dollhouses, with creating this perfect tableau.

She was very open about this.

She wrote an essay about it in an anthology edited by a friend of mine. After having a very successful career as a playwright—she had several plays produced in New York, she was written up in the New York papers—she really felt like she had to choose between her dream life, which was this dollhouse life with kids, or this other kind of artistic life. And she moved out to the suburbs and tried to create this perfect world.

In Death of a Salesman, Willy Loman misunderstood something about America. And she misunderstood something about America, which is that the idyll isn’t real. It’s a kind of advertising. At the end of her life, you get the feeling that she was finally growing out of that, but we never got to see what happened next.

What drew her and Fotis Dulos together?

He checked every box she was looking for. He was very handsome. He went to Brown University (like Jennifer). She had met him in college, and he was interested in her, but she found him to be boring. And then she met him again in her mid-30s, when she started to feel like she was running out of time to have kids. Suddenly, the same guy who had seemed boring now looked good. But she married a bad guy.

After they married, why did he start borrowing lots of money from her father?

He very much wanted to be a developer, wanted to build and sell high-end houses. And anybody who knows about that business knows it takes a tremendous amount of money. A large part of that business is how well you can raise money and manage the debt. And it almost felt like he made a deal with father, a very wealthy guy, that he would marry Jennifer, they would have kids and he would… get the money for the building company from the father.

Was money the motive for the murder?

Ultimately you don’t know the motives. Neither one of them are alive. But he had a financial motive. He was going to lose his house. And there was a belief, I think, that if he suddenly became the sole parent, he would get access to (his children’s) trust funds. But also, I think he was incredibly enraged by the whole divorce process. This was very much a men-should-be-in-charge-of-everything kind of guy. He felt emasculated by the whole process, and he couldn’t see his kids as much as he wanted.

Tell me about the reporting. In a note at the end, you write about the “astonishing” detail in the court records.

I had access to an unbelievable amount of court documents—documents filed by them, written by them as part of the divorce. We’re talking thousands and thousands of pages. My first book was published in 1998. I’ve never had access to something like this. It was one of the most contentious divorces in the history of Connecticut. At one point he represented himself and cross-examined Jennifer.

That’s an incredible scene.

He got her on the stand as if he’s going to browbeat her into a confession—of what? That he was a better parent?

And then he took the stand—and because he couldn’t cross-examine himself, he was allowed to deliver a monologue?

Like the scene in the Woody Allen movie Bananas. Basically it was him up there telling his side of the story, under oath.

You said earlier that Jennifer’s aspirations, and the way they came apart, say something about your generation. Can you tell me more about that? You’re in your 50s, like she was.

We grew up just after the Baby Boomers, and we saw the fallout of the whole ‘60s thing. We grew up with this idea that big ideas turn out to be kind of bullshit—that everybody starts with their notion of world happiness and peace, and then they end up trying to grab what they want for themselves. So I think that made our generation skeptical in a way that’s healthy.

When we were kids, all our parents got divorced. Divorce skyrocketed after no-fault divorce (first legalized in California in 1969). For people coming out of college in the 1990s, there was this idea that at a certain point you’re going to have to decide between your artistic dreams and having kids and money. I think Jennifer felt forced to make this choice.

She was in her mid-30s, so it was time to be a grown-up, to have a family.

Yeah. It’s like: I’ve experienced this (artistic) life for 10 years, and now I’m going to go live this perfect life I dreamed of when I was a little girl. And then that turned out to be not a real thing.