I’ve always loved stories about thieves who rely on their wits. When I was writing Safecracker, I thought of my hero, Grantchester “Duke” Ducaine, a little bit like he was MacGyver if MacGyver had been a third-generation crook. Duke and his sister were trained to within an inch of their lives to be the best thieves in the world, but as Duke would say, his sister’s more classical, he’s a little more jazz. The set pieces were fun to write because Duke’s an artist, not just a technician. Like a jazz musician, he sees what can be, the space in-between, the improvisation: among other things, in the first book in the series, Duke makes thermite out of a bucket of rusty bolts and aluminum foil and uses a ketchup packet to figure out the combination on a digital lock.

Sure, Duke can handle a gun, but anybody can point a pistol at somebody’s face! I wanted a character who could think — or talk — his way through a heist. I still remember my dad playing The Sting on our VCR back when VCRs were still a thing, and my delight at watching Newman and Redford always a step ahead even when it looked like they were two steps behind. But as a lifelong reader, when I was writing Safecracker, I turned to books for inspiration.

David W. Maurer’s The Big Con

Maurer was a professor of linguistics, and even though the book was published in 1940 and is, in some ways, a historical artifact, Maurer’s attention to language means the book still feels alive today. Sure, grifters are running versions of the same cons in 2024 as they were in 1924, but Maurer spent years cultivating sources within the community of swindlers so that he got inside access. Much of the charm of the Big Con is when Maurer’s cast of characters explain moves like the “cackle-bladder” or how to “sew a man up,” but there’s also something delightfully entertaining about having con men let you behind the curtain.

Elmore Leonard’s Out of Sight

My first exposure to Leonard was through the silver screen, but when I started reading his novels, that’s when I really understood how much of his work is about smart people being dumb and dumb people being smart. In Out of Sight, Jack Foley is as clever as they come. After breaking out of prison, he robs a bank by convincing a bank teller that another customer — who has nothing to do with Foley and is completely innocent — is carrying a bomb in a briefcase. And yet, he’s not smart enough to steer clear of U.S. Marshall Karen Sisco. I’ve joked that Safecracker is a bit like if Out of Sight and the Ocean’s Eleven had a baby, not just because of the heists, but because of the how much the criminals involved enjoy themselves.

Lucy Sante’s Low Life

If you’re interested in history on the margins, Sante’s Low Life is an excellent peek at the fringes of New York City from the 1840s through WWI. Again, like Maurer’s book, as you read through Low Life, you can see how some of the stories and movies that we love were inspired by the real criminal underclass, but Sante’s deep dive into the city and corruption — sex and drugs and con artists and crooked cops are only part of it — gives a rich sense of how swindlers and rogues shaped not just New York, but the American imagination.

A.J. Liebling’s The Telephone Booth Indian

Like Maurer’s The Big Con, Liebling’s The Telephone Booth Indian is a marker of a bygone era. Reading Liebling’s interview with wrestling promoter Jack Pfefer, when Pfefer bemoans that he’s not doing anything wrong — “A honest man can sell a fake diamond if he says it is a fake diamond, ain’t it?” — is just as entertaining as Liebling’s account of Maxwell C. Bimberg, who was known as Count de Pennies, try to work a hustle involving the bulk purchase of five hundred “racing” cockroaches from a burned-down bar. It’s worth noting that Sante introduces both Maurer and Liebling’s works, and between those three books, you’ve got a good sense of the history of criminals and con artists in America.

Donald Westlake’s The Hot Rock

The only thing more entertaining than watching a crook who’s good at his job, is watching a crook who’s great at his job… but who has the worst luck of any man alive. I wouldn’t go so far as to say it’s a screwball caper, but this is the first of Westlake’s Dortmunder novels, and they are all equally delightful, not because of how the criminals succeed, but because of all the ways things go wrong. The only law Dortmunder should really be afraid of is Murphey’s Law (anything that can go wrong will go wrong).

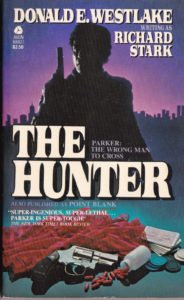

Richard Stark’s The Hunter

The Parker series is the other side of the Dortmunder coin, written by Donald Westlake under the pseudonym Richard Stark. Where Dortmunder is a funny, wry, and charming character, in The Hunter, the main character Parker, has a cold brutality to him. He’s a master blueprinter, planning heists and orchestrating all the moving pieces, fast on his feet, but he never hesitates to attack. He’s like a shark: violently efficient. But even if the main character in my novel Safecracker is somebody who’d be a lot more fun to hang out with than Parker, one of the things Duke and Paker have in common is that they both understand that it’s the attention to details that make the difference between being a free man or getting locked away for life.

Steve Hamilton’s The Lock Artist

Hamilton’s novel has a different vibe than all these other books. It’s less of a story about heists and being a career criminal, and more of a close study of a young man who learns how to unlock everything … except his own trauma. But it’s important to me because it was one of the books that inspired me to write Safecracker. Hamilton’s attention to detail — he taught himself how to pick locks as part of the writing process — make the book crackle with life.

***