I live for unlikeable women.

Not everyone agrees with me, and I’ve made my peace with that. A lot of people want their fictional women to be agreeable, attractive and easily digestible. They want them to grin more, bleed quietly, and then clean up after themselves.

I don’t write those women. And as I’ve gotten older and pickier about how I spend my time, I don’t read them much either.

What I love to write and to read are the messy, complicated and sharp-edged gals who lie and cheat and rage. They may make terrible choices, but you’d for sure want to go get a drink with them.

You know who gets to be messy and complicated and murderous? Men. In fiction and on screens around the world (also real life), male characters are allowed a sprawling range of humanity. They get to be mafia dons (Tony Soprano), amoral corporate sociopaths (Don Draper), and charming murderers (hi, Tom Ripley and Joe Goldberg), and audiences still love them. They get fan clubs, sequels and multiple season arcs.

A woman makes one snide comment and suddenly she’s “shrill.” She kills a dude and she’s irredeemable. We want our women, even our fictional ones, to follow the rules of likability.

And if you’re going to be bad? You better have a damn good reason. You better be traumatized and wounded in a way that justifies your behavior.

That’s the formula a lot of us are handed as women writers who write about women: If you want your female villain to be palatable, you must first make her pitiful. Give her a backstory soaked in suffering. Let her be broken before she becomes dangerous.

I don’t love this for us or for readers.

Not because trauma isn’t real or worthy of our exploration, but because we don’t demand this kind of validation from male characters. Men get to be terrible for the hell of it. They get to want power or revenge or be complete sociopaths just because it’s Tuesday.

When I write female villains, I don’t want to have to victimize them. Women are victimized enough in real life. Do we have to do it on the page too? I’ve stopped even focusing on making them traditionally likable. What I want to do is to make them understandable.

For me, it all comes down to motivation. What does this woman want? What does she desire so deeply that she’s willing to risk everything for it?

In The Sicilian Inheritance, I wrote a female villain named Giusy. She is completely amoral, occasionally unhinged, and undeniably a murderer. She is also my favorite character I’ve ever written. Readers of the book tell me the same thing. I’ve zoomed into hundreds of book clubs since the book was released and I constantly hear the same thing: Giusy was awful, but I loved her.

And I think that’s because Giusy’s desires are crystal clear. She wants a better life for herself and her daughter. She wants money. She wants power. She wants control in a world that has repeatedly tried to take it from her. She’s also a delightfully snappy dresser and quick with the wit.

She’s not likable in the traditional sense. She’s not cuddly. But she is ambitious as hell. And ambition, especially female ambition, can be magnetic if we just let it be.

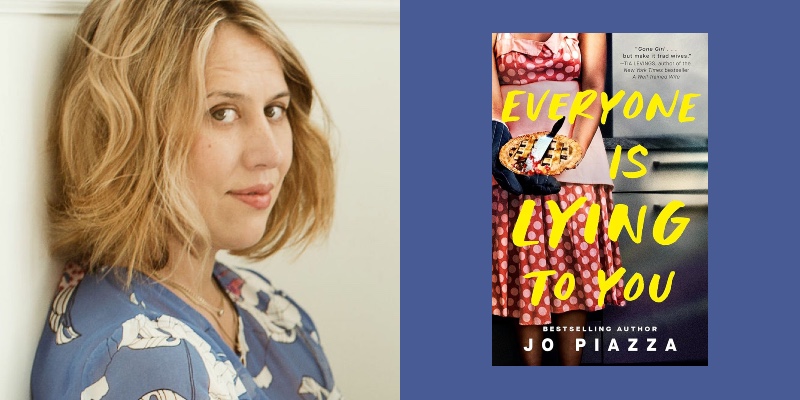

My latest book is an addictive thriller. We’ve got more than one dead body and lots of complicated women.

In Everyone is Lying to You, my characters commit their own crimes and follow their own desires. I won’t spoil the twists but I’ll say this: I didn’t set out to make these women likable. I set out to make them real. I gave them motivations that many of us share. We want love, money, freedom. Then I asked what would happen if my characters stopped apologizing for wanting those things.

I think we need to create a new definition of a likable woman villain: someone who reminds us, maybe uncomfortably, of ourselves.

I spend too much time walking in my characters’ shoes, and they all live rent free in my head. That can be a lot, but it can also be a lot of fun. Because fiction should be a chance to explore all of our desires, even the worst of them, in a completely safe place. It should also be an avenue to breed empathy, even for those who make questionable choices.

Fiction is one of the many places where women should be allowed to be all of it. Vain, selfish, vengeful, hungry. We should get to explore the full spectrum of emotions. It doesn’t just make for better stories, it lets us be seen as full humans, not just caricatures of femininity.

My characters should not have to ask for sympathy, if I’ve done my job right, you’ll root for them anyway. Or at the very least, you’ll recognize something of yourself in their chaos. And that, to me, is the most radical thing a female character can do.

***