Ask readers of crime fiction whether they have heard of John Sanford, and the writer most likely to come to mind is John Sandford, the author of the Prey series of detective novels—as they commit the common mistake of overlooking the “d” hidden in the middle of the name. But long before John Camp chose Sandford as his pen name, there was John Sanford—author of 24 books, including two hard-boiled 1930’s masterworks that combine gut-wrenching plots with a literary flair that drew favorable comparisons with William Faulkner, Ernest Hemingway and James M. Cain.

Sanford, who died in 2003, is best known as a writer of non-fiction—including creative interpretations of American history, two of which were hailed as “masterpieces” by the Los Angeles Times; memoirs; and a five-volume autobiography. Less well-known are the crime writing origins of his craft. This is largely due to these early novels’ being out of print for over sixty years. The Cambridge Companion to Jewish American Literature calls Sanford “perhaps the most outstanding neglected novelist” in America. With Brash Books’ reissue of 1935’s The Old Man’s Place and 1939’s Make My Bed in Hell, crime writing devotees have an opportunity to end this unjustified neglect.

In the depths of the Great Depression, after a James Joyce-influenced modernist first novel that did not sell, Sanford was determined to make his second novel a popular success. He set The Old Man’s Place in the New York mountain hamlet of Warrensburg—in which he would also place his next two novels—and used as his basis a true story about a gang of poachers who had terrorized the Adirondack countryside. Sanford altered the characters to a trio of World War One veterans, who return to the family farm on which one of them grew up, unleashing a wave of mayhem. When one of the group lures a naive mail-order bride to the homestead, the plot accelerates toward its bloody climax. Sanford tells this tale in language honed to a stark, slashing edge.

When The Old Man’s Place appeared in 1935, many reviewers were put off by the violence and depravity it depicted. However, others commended Sanford’s vivid, muscular prose. The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette wrote: “Sanford is a supreme master at squeezing the last drop of terror and excitement out of a sordid, savage situation. The story sweeps along with an ugly force that will send sensitive souls in search of smelling salts.” The New York Times called the book “A first-rate piece of swift-moving and dramatic story-telling.” Other papers hailed The Old Man’s Place as “a robust tale of violence, lust, treachery, and murder,” “a good, exciting story told with menacing simplicity,” and “vivid, realistic, skillful, dramatic.” The highly influential New York Times reviewer John Chamberlain praised how Sanford captured the violence lurking beneath the nation’s pastoral surface: “the occasional flaring of brutality of the American character.”

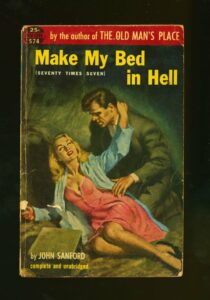

In 1939, Sanford followed up with what I regard as his finest novel. Originally titled Seventy Times Seven, this book was reprinted in the 1950’s as a pulp paperback and called Make My Bed in Hell. Sanford set it, again, in Warrensburg. One bitterly cold winter morning, the protagonist discovers that a man has staggered into his barn and lies dying in a horse stall. He soon realizes that this man is no stranger but rather someone who had bullied him during their youth. In the intervening years, the intruder has lived a carefree vagabond lifestyle, while the farmer has broken his back trying to eke a living from the played-out fields that are his bitter patrimony.

Sanford interweaves three different voices in Make My Bed in Hell’s narrative: the farmer’s description of events; the intruder’s delirious, rambling memories of his past; and testimony from an inquest to determine whether the farmer should be charged over his failure to render aid. Midway through Make My Bed in Hell, Sanford adds a fourth narrative perspective in the form of a blank verse poem depicting violent episodes in American history that focus especially on Americans’ mistreatment of the native populace. Sanford aimed to depict the farmer’s callousness and the villagers’ cruelty as the natural inheritance of the bloody reign Europeans unleashed with their conquest of the continent. Although some readers may at first be taken by surprise by the unconventional structure, the overall result is an engaging and powerful narrative that combines stylistic flourish with a visceral, propulsive plot.

As with The Old Man’s Place, some reviewers felt revulsion about the violence depicted in Make My Bed in Hell. But the Los Angeles Times expressed particular appreciation for the historic section: “[Sanford] is filled with ideas and tried to get the whole of America into a brief, fast book of less than 200 pages, and those pages terse…. Sanford has injected the drama of spilled blood that made America…[in] a long blank-verse section of tremendous power.” The New York Times wrote: “The prose is fresh and energetic, the story-telling superb, and the writing comes out raw and terrifying as an exposed nerve…. This novel stands high as a piece of realistic writing…[with] stylistic variety that few authors now writing can manage.” Other reviews called Make My Bed in Hell “electrifying” and “a first-rate story of violence and congealed hate” told with “brilliant” writing.

* * *

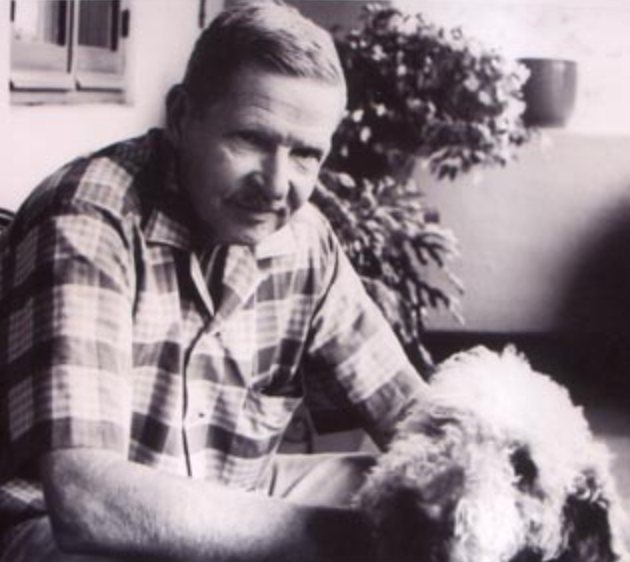

John Sanford was born Julian Shapiro in 1904 in Harlem, New York, the child of Jewish immigrants. He died in 2003 in Santa Barbara, California. Along the way, he became a lawyer, a Hollywood screenwriter, an ardent Communist, and a victim of the McCarthy blacklist. Though Sanford began as a novelist, at the age of 63 he commenced the prolific second act of his long career, that of a non-fiction writer. In fact, Sanford published half his books after he had turned 80, an age when most writers are retired…or dead. Though his early novels were issued by America’s premiere publishing houses, in his later years he struggled to find outlets for his work. Still, despite his obscurity, Sanford maintained the vehemence of his creative vision and continued writing until shortly before his death at age 98. Sanford won a PEN award for the first installment of his superb five-volume autobiography, Scenes from the Life of an American Jew, as well as the Los Angeles Times’s Lifetime Achievement Award. Just before his death, the L. A. Times called Sanford “an authentic hero of American letters.”

Sanford’s birth name was Julian Shapiro. His father had immigrated from Russia, and his mother was born in Manhattan’s Lower East Side slums. By the time of Sanford’s 1904 birth, the father had become a lawyer, and the family was living in the fashionable Jewish neighborhood of Harlem. However, Sanford’s childhood was rocked by his father’s financial setbacks and his mother’s death, after a lengthy illness, when he was ten. In the wake of his mother’s passing, Sanford became alienated from his family and indifferent toward his education. He never graduated from high school, because he was caught cheating on an English test his senior year.

After a feckless, abortive college career, Sanford decided to follow in his father’s footsteps. In 1924, he entered Fordham Law School, from which he would obtain a law degree. Classes met on the 28th floor of the Woolworth Building in downtown Manhattan, then the tallest skyscraper in the world. One of his professors was Joseph Force Crater; Judge Crater’s infamous, never-solved 1930 disappearance made him the Jimmy Hoffa of the Depression era.

The most significant event of Sanford’s law school years happened while golfing by himself in New Jersey, where he chanced upon another solo golfer whom he recognized from his Harlem days—Nathan Weinstein. However, the young man was now going by the name of Nathanael West. Sanford bragged to West that he was attending law school. West’s reply stunned Sanford: he was writing a book. From that day forward, the words writing a book dominated Sanford’s thinking, and his legal studies instantly lost their appeal.

West and Sanford frequently wandered the streets of New York together, with West lecturing his companion about art and literature. Sanford was hungry for a mentor, and West seemed pleased to have a disciple. West introduced Sanford to the work of James Joyce and Ernest Hemingway, and Sanford undertook a crash course in reading to make up for the intellectually barren years after his mother’s death. Later, the pair would spend a summer together writing in a rented hunting lodge in the Adirondacks, where West worked on Miss Lonelyhearts and Sanford completed his first novel, The Water Wheel, about a dissatisfied New York lawyer longing to be an author. Sanford would draw on the nearby hamlet of Warrensburg for the setting for his next three novels, which bored deeply into the brutality of the American psyche.

After graduation from Fordham, Sanford joined his father’s practice. His experience as a lawyer had enduring effects on his writing. During a trip to the country, Sanford was recruited to defend a minister accused of fathering an illegitimate child with an underage servant. That episode became the basis for one of his first published short stories, 1932’s “Once in a Sedan and Twice Standing Up,” whose salacious title caused it to be dropped from the highly anticipated first issue of Contact, edited by West and William Carlos Williams. And from his second novel onward, Sanford typed all his manuscripts on a manual typewriter using blue-ruled testimony bond, which became increasingly difficult to find during the computer age.

The Water Wheel (reissued in 2020 by Tough Poets) was Sanford’s only book published under his birth name. A highly experimental work heavily influenced by Joyce’s Ulysses, the novel is full of wordplay and stream-of-consciousness. Shortly after its 1933 issue, the publisher went bankrupt. While winning praise from other writers such as Williams, it failed to sell.

In the depths of the Depression, Sanford was determined to make his second novel a popular success. He set The Old Man’s Place in Warrensburg, adapting the story about poachers. On the advice of West, to avoid potential readers’ rejection of a book by a Jewish author, Sanford chose as his pen name the name of his Water Wheel protagonist—the lawyer dreaming of being a novelist, John Sanford. From then on, he would write as Sanford.

Despite some positive reviews, Sanford’s hoped-for sales did not materialize. However, The Old Man’s Place brought him to the attention of Paramount Studios, which summoned Sanford to Los Angeles in 1936 to be a screenwriter. Sanford’s year as a contract writer at Paramount did not result in a filmed script. But the New York transplant found himself caught up in the life of Hollywood. For a while, he dated starlet Jean Muir. He also was a frequent guest at Joan Crawford’s house for dinner. The most momentous event, though, was meeting in a Paramount hallway an up-and-coming screenwriter named Marguerite Roberts.

Sanford and Roberts soon became a couple, and they wed in 1938. Roberts went on to become one of the highest paid screenwriters at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, scripting films for the studio’s A-list stars. Sanford and Roberts co-wrote the 1941 comedic Western, Honky Tonk, which starred Clark Gable and Lana Turner. Toward the end of her career, Roberts wrote the screenplay for John Wayne’s Oscar-winner, True Grit.

Honky Tonk (1941)

Honky Tonk (1941)

Sanford had already begun his third novel before heading west. After failing to keep work as a screenwriter, he returned to Make My Bed in Hell, often writing in Roberts’s back yard. This novel built upon an early short story “I Let Him Die.” While working on Make My Bed in Hell, Sanford was courted by the Communist Party. The 1950s’ anti-Communist backlash and the Cold War have made contemporary Americans’ view of the extreme left much more negative than the public’s view was during the mid- to late-1930’s. Sanford arrived in Hollywood amid a major unionizing push, which was led by screenwriters. Labor strife was rampant across the country, and anti-strike violence was at a peak. In fact, a 1942 magazine poll reported that a full quarter of the American population “favored socialism.”

By the time Sanford joined the Party, Make My Bed in Hell was well under way, so its themes are more ethical than political. But Sanford’s next three novels—1943’s The People from Heaven, his last set in Warrensburg, 1951’s A Man without Shoes and 1953’s The Land that Touches Mine—were explicitly political. Sanford’s explosive radicalism was so intense that it gave even the Communist Party jitters: the Party tried to suppress publication of The People from Heaven, fearing it would lead to a premature racial revolt. And in A Man without Shoes, Sanford at times lapses into Marxist lectures, diminishing the impact of the novel as a novel.

In 1951, Sanford and Roberts were subpoenaed to appear before the Los Angeles hearings of the House Committee on Un-American Activities. Sanford took the Fifth Amendment and declined to answer questions about his political affiliations. Roberts asserted that she was not a member of the Communist Party but took the Fifth when asked whether she ever had been. Both refused to name names and both were blacklisted. The impact on Roberts was catastrophic: M-G-M canceled a just-signed five-year contract. Though Sanford was not barred from writing books, he found it impossible to compose while his wife suffered through a ten-year professional banishment. Even reissuing The Old Man’s Place and Make My Bed in Hell in pulp paperbacks was complicated by the blacklisted Sanford’s name being anathema to publishers.

In 1961, Roberts was the second screenwriter to return to work after the dissolution of the blacklist. His wife’s career renewal enabled Sanford to write again. He published two more novels, the final one making clear that fiction-writing had run its course for Sanford. It was then, in 1967, that Sanford embarked on his second career—that of a non-fiction writer.

Sanford published books in eight decades. He wrote works of uncannily beautiful prose that also did not shy away from depicting the grotesque and brutal violence that is the undercurrent of American life. With Brash Books’ reissue of the first two volumes of Sanford’s Warrensburg trilogy, the reading public finally has access again to the crime writing origins of Sanford’s lengthy career. For the reader interested in vivid, entertaining crime writing, The Old Man’s Place and Make My Bed in Hell will not disappoint. For those seeking a bit more, Sanford’s language—written for how it sounds to the ear and looks on the page—will reward the reader with prose of a master craftsman, as good an any writer’s in the genre.