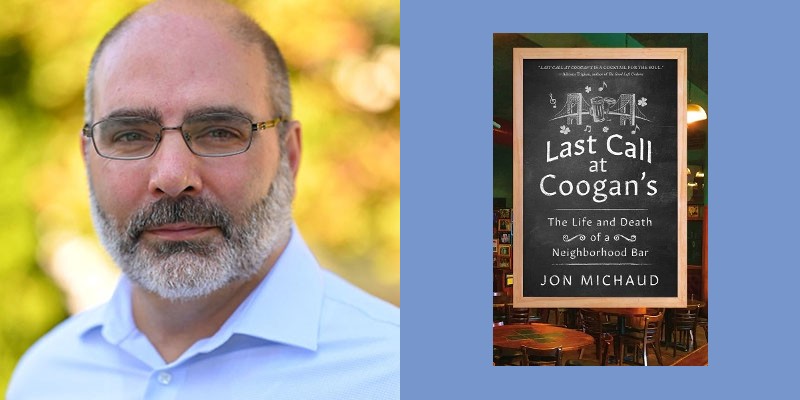

I’ve often, in my mind, likened the perfect reading experience to sitting in a bar and finding myself drawn—at first reluctantly, then less so all the time—into a stranger’s story. There’s something unique and compelling in that narrative space, and it’s an effect Jon Michaud conjures up masterfully in his new book, Last Call at Coogan’s: The Life and Death of a Neighborhood Bar.

For a span of about thirty-five years, until its 2020 closure, Coogan’s was an uptown institution: an Irish bar in a Dominican stronghold, marrying the saloon ideals of a bygone New York with the practical, workaday concerns of a neighborhood in need of meeting spaces. Michaud, a talented novelist with longtime connections to the area, brought to the project a deep appreciation for the bar’s place in civic life.

The result is a profound story of a community in flux—a timeless New York story, that is, and one that has room for the sweeping forces at play in the city as well as the deeply personal stories that mix and mingle in any saloon worth its taps. I caught up with Michaud before the book’s release to discuss how the project began, how Coogan’s captured his imagination, and the qualities that define a neighborhood bar.

Dwyer Murphy: You obviously spent a great deal of time with the owners of Coogan’s and were given tremendous access to the life of this bar. How did they first respond when you approached them about this? Were they at all wary?

Jon Michaud: It all started with this New Yorker piece I wrote, when Lin-Manuel Miranda and Adriano Espaillat and Lin-Manuel’s dad essentially led the effort to save Coogan’s from going out of business due to an extreme rent hike. That was in January 2018. I called up Coogan’s and asked to talk to the owners. I had met one of them, but I didn’t really know them, and they didn’t know me. It was Peter Walsh who answered the phone and he said, ‘oh you’re writing for the New Yorker? I love the New Yorker. When do you want to come?’

I thought I was going to get ten minutes with them, because they had just come out of this huge wave of publicity and I figured they would be exhausted, but I ended up talking with all three of them—David Hunt, Peter Walsh, and Tess O’Connor McDade—for two hours in the back of the bar. It was an amazing conversation, and I walked out of there thinking how much there was to that place, and how it would have all been lost if they had closed.

So I wrote my article, but I just couldn’t stop thinking about Coogan’s. They were very pleased with the article and the response to it. Finally, I pitched the idea of a book to them, because as I say, this huge legacy, all these stories, all the lore about the bar would have been lost. They are a naturally collaborative group of people. Throughout their careers, they’ve worked with artists and writers, so collaboration is a natural state of them. It’s one of the reasons they’ve been so successful in the hospitality business. So, they said yes. They were completely open with me for the entire process. We never had any kind of adversarial interaction in the five years I was working on the book.

Murphy: I got the impression the owners had an appreciation for the spirit of a good bar and what it could mean to a neighborhood. It almost seemed like they were waiting for someone to come along to tell the story.

Michaud: All three of them are terrific storytellers. And, of course, that’s part of owning a bar. A bar is a venue for storytelling. Peter himself wrote a musical about a bar. He spent decades working on this shadow chronicle of Coogan’s. So, he had been thinking about it as a narrative, and he understood how bars work within their communities. They all had very clear ideas about that. But I do think they were waiting for someone to come along and ask to write about it.

Murphy: Can we talk about Washington Heights and about the specific block where Coogan’s is located? The terrain, this distinct part of New York City, is so important to the bigger story.

Michaud: The bar sat at the crossroads of Washington Heights, which is a neighborhood in the northern part of Manhattan, north of Central Park, north of Harlem. It’s the part of New York that often isn’t shown on maps of Manhattan. It’s historically significant: a culturally rich and diverse section of the city. It developed later than the rest of Manhattan, in the late 19th to early 20th century. A lot of the original landscape of the island is still visible there.

Washington Heights is a neighborhood many immigrants went to. Immigrants on the Lower East Side, Irish and Jewish, once they got out of tenements housing, went there for a little more air, more space. That was abetted by the construction of subways at the end of the 19th century. So, it was a neighborhood that underwent waves of immigration. The Irish were strong there for a long time. You had African-Americans in the southern part of the neighborhood who had moved in during the Great Migration. Then later you had Greek and German-Jewish immigrants. And then, ultimately many, many Dominican immigrants who started arriving in the late 60s and early 70s. For a while, Washington Heights was the second largest Dominican settlement in the world, after Santo Domingo.

And that’s about where the story beings: in this transition from being an Irish and Jewish neighborhood to a primarily Dominican neighborhood. At that time, crime was increasing, and opportunities were decreasing. Washington Heights was under-serviced by the city. It suffered badly during the financial crisis in the 1970s. Coogan’s opened in 1985, when crime was on the increase. The murder rate crested, I think, 1989 or 1990. You had the crack epidemic, and Washington Heights was the epicenter for the drug trade, not just in New York but on the whole east coast of the United States. It was a complex, rich neighborhood to write about.

Murphy: You have an interesting quote in the book, somebody who reflects on the affinities between the Irish-American and Dominican-American experiences in New York City, and how those communities grew.

Michaud: That was a priest at one of the local parishes who was bilingual. An Irish priest. He commented on the similarities between the Irish and the Dominicans: both countries that were once dominated by nearby colonial powers, both majority Catholic nations with a love of dancing and drinking and storytelling. I think these Irish owners of this bar felt perfectly comfortable with their Dominican clientele.

Murphy: And they chose the location very carefully.

Michaud: Location was definitely part of their success. They’re on top of a major subway station. A few blocks from the George Washington Bridge and the bus station. A few blocks from the New York Presbyterian Emergency Room. So that’s a major crossroads. A lot of people come in and out of there and many of them needed a bite to eat or something to drink, and Coogan’s was there to welcome them all.

Murphy: Let’s talk about the role of a good bar in a community. That’s a subject that occupied your attention during the process of writing this book, I take it: the question of the “moral pub.”

Michaud: One of my touchstones was this essay that George Orwell wrote about this fictional bar in London that he described as the ideal London bar. He delineated the qualities of the bar and what it should have and what it shouldn’t have. I took that idea and transposed it to New York.

I thought about how, if I was writing about the ideal New York City saloon and I arrived at a list of qualities, many of those qualities would be shared by institutions that are vital to New York City as a multi-cultural, multi-ethnic place. I’m thinking of the subways, the parks, and the libraries. They’re open to all. There’s an egalitarian element to the way people are treated when they’re there. Status doesn’t really matter.

A lot of those qualities were qualities that Coogan’s had and strove to maintain. The owners loved the idea that they could have a surgeon sitting next to a transit worker at their bar and they would be treated the same way. I think that’s fundamental to New York’s neighborhood bars. There are of course the kind of clannish places where everyone turns their heads when you walk in, and outsiders are shunned. But Coogan’s was very much the opposite kind of place. They were looking to welcome people, to bring them into the fold. All of those qualities were essential to Coogan’s success.

Also, they had a deeply rooted sense of the history of pubs, both Irish and American. David Hunt had worked in bars in Greenwich Village before opening Coogan’s, and he had grown up in Inwood, which is famous for its many Irish saloons. And Peter Walsh had spent a lot of time in Ireland and talked about the role Irish country pubs played in society in rural Ireland. He wanted Coogan’s to have many of those same functions.

Murphy: Irish pubs were the setting for your own formative bar experiences, as well.

Michaud: Indeed, I spent my teenager years in Northern Ireland. From the age of fifteen, I was drinking in Belfast bars, in a wet cold city. This was during the Troubles, so bombs were going off, and there was the ring of steel around the center, where cars were checked for bombs, and everyone got frisked. But at the same time, you had a number of very welcoming Irish bars, and that’s where I spent a great deal of time in Belfast. When I first got to New York, I went looking for places that reminded me of the bars I remembered from Belfast.

Murphy: I worry about the future of bars in New York, neighborhood bars especially. Obviously, the pandemic impacted those places tremendously. But before that, I think the experience had changed. People in bars—and I’ve been as guilty as anyone—spend time on their phones. The social aspect of the space is completely different.

Michaud: The owners of Coogan’s fretted about that. Peter Walsh had a line: ‘social media is anti-social.’ They liked to recall when Monday Night Football was launched, and how everyone would go into the bar on Monday nights to watch games. But now you have high-definition TV in your home; you can watch any sporting event from the world on demand and have food from every restaurant in the city brought to your door. Why would you go out to a bar?

The reason you might go to a bar is to meet other people—to interact with people you don’t normally interact with. This goes to the very roots of the problems the country is facing. We’re self-selecting our social circles. We’re no longer putting ourselves in positions where we have to converse with people who are not like us. That was one of the great functions of a bar. You would go and, lubricated by a beer or two, you would discuss the issues of the day, often with people who disagreed with you, but it would be civil and healthy. I’m concerned that’s happening a lot less.

There are still a number of neighborhood bars in New York. An Beal Bocht, for example: an Irish bar in the Bronx, which still has that neighborhood vibe to it and people still go to hang out with their neighbors and to talk to people. Those saloons, they’re still there, but the demand is shrinking, and I worry about what that means for the country.

Murphy: What kind of bar literature were you looking to, for this project? Joseph Mitchell’s Up in the Old Hotel came to mind as I was reading.

Michaud: I’ve long been a fan of Joseph Mitchell’s work. When I was working as a bookseller at Rizzoli in the 90s, I got to meet him. He came in to sign copies of Up in the Old Hotel. They had just reissued The Bottom of the Harbor in Everyman edition. So, I have signed copies of those. They’re treasured items in my library. I acknowledge a debt to Mitchell, not just to the McSorley’s story, but the “Up in the Old Hotel” story, which is about Sloppy Louie’s, of course. And he had another great piece about the tradition of beefsteak dinners at the New York social clubs, “All You Can Hold for Five Bucks.”

When I was starting out on this project, I didn’t find too many books like the one I wanted to write: narrative nonfiction about a bar. There were a couple. I loved Rosie Schaap’s memoir, Drinking with Men, and there was another book called Sunny’s Nights, by Tim Sultan which is about a bar in Red Hook. And a gorgeous book called The Last Fine Time, by Verlyn Klinkenborg, which is about a Polish saloon in Buffalo. And then of course there’s J.M. Moehringer’s The Tender Bar, which is a memoir and, with the exception of Mitchell, might be the greatest ever rendering of a bar in a work of nonfiction. But I liked that weren’t too many books on the subject. It gave me some latitude.

Murphy: You were bringing a novelist’s eye to the subject, too. The book has these wonderful character studies that break out of the main narrative. Were there figures you met along the way that you immediately recognized would need to have their piece of the story?

Michaud: Some of them, I knew in advance. The owners had tipped me off about who I had to talk to. Other people, I would just meet in the course of doing my interviews, and stories would mushroom up and I would think, ‘I have to give you a chapter.’

One of them is the story of Darren Ferguson and Taz Davis. Darren was an aspiring singer who grew up in Washington Heights. He became addicted to cocaine and was living with his grandfather at the time. He got behind on the rent and had a moment of crisis where he decided that, to make all his problems go away, he was going to set a fire in his grandfather’s apartment. He set the fire and walked out. Later, he learned that an older woman who lived above the apartment died in the fire. He was arrested and served a number of years in prison. While he was in prison, he discovered his faith and became an ordained minister. He came out and his choir sang at the first Coogan’s 5K race, and Peter Walsh invited him to participate—to sing—in the production of his play about this Irish bar. During rehearsals, Peter introduced Darren to this guy named Taz. It was Taz’s surrogate grandmother who had died in the fire. And while Darren was in prison, Taz had been sending him messages that said, basically, ‘if I see you, what happens happens, and I’m not going to be held responsible for how I respond.’ But in that moment in Coogan’s, when Peter introduced him, Taz grabbed Darren and said, ‘God forgives you and so do I.’ Then the two of them went on stage and performed together.

When I heard that, I knew I would write about them, not only because it’s a remarkable story on its own, but because it shows the power of a place like Coogan’s to bring people together.

Murphy: People come together differently in a bar.

Michaud: The importance of having a space like that in the neighborhood can’t be overstated. It was a neighborhood that for much of Coogan’s history was a very tense place, a neighborhood where people from different ethnicities distrusted one another. So, to have a place—and there weren’t many of them—where these different groups could meet and talk to one another was essential to the functioning of that society and the pulling together of the community during those difficult years. Coogan’s didn’t do that on its own. But they collaborated with many of the community figures who were stiving to improve life in the neighborhood. They collaborated with non-profit organizations, the police, politicians, sports coaches, all of these people who were working together to make life better. Coogan’s was a place they could interact and collaborate and work together.